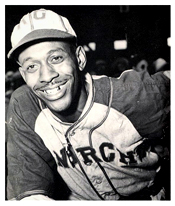

The 1920 Caulfield Ads (from the New Orleans Old Timers Baseball Club Collection, Amistad Research Center, New Orleans, LA)

This post kind is kind of a spin-off of my one yesterday about Satchel Paige and the New Orleans Black Pelicans. During the year examined, the Black Pelicans were owned by a local businessman named Fred Caulfield, whose other endeavors included retail sales and event promotion. (The Black Pels went through various incarnations, owners, management and quality/level of play over the several decades the team name existed. That in itself is a fascinating, attention-deserving story. Maybe soon …)

In a city of overlooked blackball legends, Fred Caulfield is easily one of the most overlooked, even by myself, an alleged “expert” on NOLA and Louisiana Negro Leagues activity. The more I read about him and the more I delve into his personal and professional life, the more I realize how important he was to Big Easy African-American baseball. He’s rapidly becoming, at least in my own weird little mind, the second-most important baseball businessman and impresario in New Orleans Negro Leagues history, second only to the great and peerless Allen Page and even greater than the 1880s figure Walter Cohen).

Caulfield’s most recognizable claim to fame, largely because of the name thing, is as the proprietor of the Caulfield Ads, a local African-American team whose origins date before 1920 and who, over the span of a couple decades, went through several incarnations that varied in both talent quality and level of play. At times, the Ads weren’t much more than one of the better sandlot teams in the Crescent City, while at other times they were arguably the best pro team in the city and members of respected regional southern leagues.

The Ads were also rivals to numerous other longtime NOLA semi-pro/pro teams — a few which, as it turns out, were themselves owned and/or promoted by Caulfield himself — such as the Black Pels, the Crescent Stars, the Algiers Giants and the Jax Red Sox.

But as his influence apparently grew, Fred Caulfield branched out to own other teams, like the Pels and, near the end of his life, the Red Sox, who, in 1938, provided him a sort of “last hurrah” as a baseball kingpin.

New Orleans native Fred Caulfield, according to his WWI draft registration card, was born July 26, 1880. His parents were Jules Caulfield and the former Marie Martinez. Jules and Marie were both born in Louisiana, but they each were both half-European — Jules’ father was born in England, while Marie’s dad was birthed in Spain. I need to do more research into Jules’ and Marie’s lives and ancestral backgrounds, something I hope to do soon. (I will note here, however, that my next post also will be about another New Orleans Negro League figure who had one parent born outside of the country.)

The fact that Fred Caulfield embodied such a cultural melange raises mysteries about his exact ethnic identity. The 1910 federal Census, for instance, lists him as a “mulatto” resident of Orleans Street in the city. His listed occupation is as a “collector” for a furniture company.

But in the 1920 Census, Fred Caulfield — as well as both of his parents — is listed as “black,” as is his wife, the former Carrie Robertson. The two couples were living next door to each other on Conti Street. Fred Caulfield ran a grocery, while his father is listed as a “laborer.”

Fred Caulfield moved from Orleans Street to Conti Street sometime between 1910-16. His draft card, signed in 1918, states that he lived at 2405 Conti Street, while his occupation is noted as “grocery & bar.” By 1930, he and Carrie were living with her parents, and the Census that year indicates that he had become a baseball man full time, a “manager” of a “ball team.”

Which leads us to his baseball career. His first and most well known outfit, the Ads, was birthed at least as early as 1918, according to reports, and in 1919 they and three other black teams joined to re-form a “Colored City League,” according to an article in the 1919 New Orleans States newspaper:

“The Colored City League has re-organized for the season and will start a 25-game series Easter Sunday at the National Park, Third and Claiborne,” the article stated. “The league is comprised of the Caulfield Ads, Fred Caulfield, manager; I.C.R.R., Leon Augustin, manager; All Stars, Walter Pittman, manager; Clio [or possibly Cico], Joseph Pye, manager.”

(The ICRR likely referred to the Illinois Central Railroad, which apparently had a terminus in New Orleans.)

The CCL opened play April 20, 1919, with the Ads playing to a 3-3 draw with the ICRR. But July, the Caulfields were leading the league. Late that month, Fred’s bunch played the All Stars in the featured game of a CCL doubleheader. After that, media coverage of the league drops off.

By the next season — the photo at the start of this post pictures that squad — the Ads had stepped up in the world, joining what an April 27, 1920, newspaper article called “[T]he negro southern league.” Here’s a little more from the article:

“[T]he Caulfield Ads of New Orleans leave Tuesday night for Pensacola to play the opening game there.

“The Caulfields will play their first 20 games on the road, making almost the entire circuit. …

“The home opener for the local negroes is schedule for May 20 with Montgomery. All games in the regular [white] Southern League cities will be played in the Southern League parks.

“Fred Caulfield has changed up his line-up considerably and says he is taking a stronger team than has played in the local games. …”

The team seems to have included Fred’s brother, Jules Caulfield Jr., as a pitcher, and Winfield Welch in left field; Welch would gradually go on to national fame as manager of the two-time league-winning Birmingham Black Barons in the mid-1940s.

Over the next decade-plus, the Ads ebbed and flowed in terms of quality, sometimes making up part of a southern circuit, other times existing as a barnstorming aggregation that criss-crossed the state and region. And, as revealed by the 1926 Satchel Paige scenario, Fred Caulfield himself also dabbled with other teams, including the Black Pelicans.

In May 1934, the Associated Negro Press reported that “Fred Caulfield, the first man to give the city a professional baseball club, plans to stage a comeback this season with his Caulfield Ads outfit. He plans the use of two parks, the Pelican park when the [white minor-league] Pelicans are not home; and the Lincoln park at other times.”

The entire time, though, Caulfield appears to have had the respect of his players, who, according to a 1979 article in the New Orleans Times-Picayune, stirred “fond recollections of businessman-sportsman Freddie Caulfield who owned the Caulfield Ads and later the Pelicans.”

The article then quoted former player Walter Wright about Caulfield: “If he gave you a contract, he’d pay it. One time they had two straight days of rain and he paid everybody.”

But by the mid-1930s, Fred Caulfield was well into his 50s and becoming the “old man” on the local baseball promotion circuit. But he didn’t give up his clout without a fight, as evidenced by what he died in 1938 …

That year, Caulfield brought together and skippered the Jax Red Sox, a team sponsored by longtime and beloved Jax Brewery — the business has, however, long since been gone, and the brewery space is now a commercial/apartment complex — who, as evident in the Louisiana Weekly ad below, put forth “Colored Baseball’s Southern Champions.” The ad, umm, adds: “Your favorite baseball team sponsored by your favorite beer.”

The Red Sox played many of their home games in Pelican Stadium, where, according to the ad, admission was 25 cents to 40 cents.

The Jax squad spent the entire summer squabbling and jockeying with the New Orleans Sports for supremacy on the Big Easy blackball scene. It was, apparently, quite the heated rivalry, one played up by the Louisiana Weekly, the local African-American paper, and one that drew grousing from “lesser” teams that thought they merited a place at the local championship competition table as well.

While the Sox were dueling with the Sports locally, they also toured the state and region playing more far-flung squads — some of which Jax also hosted in NOLA — like the Galveston Grays, with whom the Sox split a late-June doubleheader at Pelican Stadium; the Houston Blackcats, who blasted the Sox 10-1 in mid-July; and the Shreveport Sports, with whom they played a pair of home-and-home doubleheaders (four games in all, two in each city) in August.

For much of the 1938 Jax season, the mound ace was famed longtime local hurler Robert “Black Diamond” Pipkins, who had an esteemed, if a bit mythical, career at various levels of local, regional and national play.

The Sox also featured the services of multi-faceted local legend Herman Roth, and late in the season, Caulfield brought in two ringers who had been plying their trade in central Canada, George Alexander and Freddie Ramie. Ramie was the prized catch — an Aug. 6, 1938, article in the Weekly had lavished praise of the well traveled local youngster, saying he “is enjoying a brilliant season as a pitcher with the Broadview Buffs in Canada. He has compiled the good record of 9 wins, 3 losses and two ties. … Young Ramie expects to leave Canada for New Orleans on August 15.”

Which was just in time to bolster Caulfield’s squad for the match-up that was apparently desired, after several rain outs and other delays, by the entire city populace: A championship showdown between the Rex Sox and the Sports. Beginning Aug. 21, it was on.

And on the eve of the clash, some in the local media, including Weekly columnist Eddie Burbridge, were already hyping it up.

“Freddie Caulfield, manager of the Jax Red Sox, will put his team against the New Orleans Sports in a five-game series for the city championship, starting Sunday with a doubleheader at Pelican Stadium,” Burbridge wrote in the Aug. 20 Weekly. “Fans are in for some great baseball, as Manager [Curtis] Tankerson of the Sports is really pointing for the Red Sox.”

While Jax had Pipkins, Ramie, Roth and other local heroes studding its lineup, Tankerson boasted his own impressive roster, including pitchers “Schoolboy” Melrose and Dan Boatner.

The showdown seems to have lived up to its billing — after a pair of split doubleheaders, by the last week of August the series stood at two games apiece. In the second DH, Boatner easily greased the Red Sox 4-0 in the opener, while Pipkins did his thang in the second game, securing a comfy 10-2 revenge win for Jax.

At that point, things get a bit clouded. The Sept. 10 Louisiana Weekly carried a surprisingly brief — it was a single paragraph with barely a headline — article stating that, “In four games played Sunday and Monday afternoon, the N.O. Sports won two and tied one with the highly touted Jax Red Sox.” After a couple sentences describing the four contests, the article didn’t even officially declare a winner of the “city championship.”

And that appears to have been it for Fred Caulfield and his team’s 1938 campaign. It also might have been Caulfield’s swan song as well: Just over three years later, the NOLA baseball legend — arguably the city’s first black hardball kingpin — was dead at the age of 61, passing away at his Conti Street home Dec. 17, 1941, a week and a half after Pearl Harbor.

“Mr. Caulfield was one of the best-known and best-liked baseball promoters in the South,” stated the Dec. 27 Louisiana Weekly, “having managed such outstanding teams as the early edition of the Crescent Stars. For the past several years, he managed the Jax Red Sox. He was also well known in the business world, having conducted and beer parlor at Conti and Dorgenois Streets for a long period of time.”

He left behind his wife, Carrie; his brother, Jules Jr., and two aunts. But when he died, a crucial era of New Orleans Negro Leagues history ended with him. For more than a decade, Fred Caulfield was black NOLA baseball, a torch that subsequently was passed to Allen Page, who carried the flame into the 1950s and the end of segregation.

Caulfield was hugely responsible for restarting top-quality African-American baseball in the Crescent City, which had suffered a lull in such matters since the 1890s, when Plessy V. Ferguson formalized Jim Crow in Louisiana and the rest of the South and put an end to the first era of fantastic black baseball (as played in the 1880s by the Pinchbacks, Cohens, Dumonts and others).

I continue to be ashamed that I overlooked Fred Caulfield’s contributions for such a long time. Hopefully, this blog will help to start rectify that grievous oversight.