“I am a public relations officer, and I can say without a doubt right now that nothing like that ever happened here.”

Yes, I’m a researcher. I deal in databases and microfilm and files of old documents and pictures and stuff.

But in a previously life, I was an investigative journalist. A hard-as-nails-one. I asked people hard questions, backed them into a corner and got action because of it. In essence, I could be a bad ass, journalistically speaking.

But you see, that never really completely leaves you, that urge for doggedness and grit and pulling answers out of someone. And, quite especially and deliciously, proving someone wrong and rendering them, if only for a moment, speechless and dumbfounded. True, there’s a healthy dose of schadenfreude involved, but it comes with the territory of taking no, umm, poop.

I reverted to that former self yesterday because I decided that, to a large extent, I’m done fooling around when it comes to finding out what happened to Cannonball Dick Redding in Pilgrim State Hospital on Long Island in 1948.

Since my last few posts about this (here, here and here), I’ve been waiting to hear back from modern-day Pilgrim Psychiatric Facility about my request for the release of records from there — I’m not optimistic, given New York State’s strict patient privacy laws, even though that patient has no living relatives and has been dead for more than 65 years — and I sent a formal request for records from military services since Redding served in the Army in WWI.

But we journalists at heart are not a patient bunch. Not in the slightest. So I guess yesterday I took off the gloves and threw down the gauntlet.

I did so by calling up Pilgrim and asking form the public information officer at the center, Ms. Sara Kalvin. Let’s just say that during our roughly 20-minute conversation, I dropped the terms “murder,” “abuse” and “cover-up.”

Like the title of this post says, I’m done foolin’ around. And my, shall we say, aggressive questioning got Ms. Kalvin to pop out the quote with which I led off this post.

I had to explain who Dick Redding was, and I had to give some rudimentary background about what the Negro Leagues were pre-Jackie. She gave me the same basic line I’ve been hearing from various state officials regarding state privacy laws and the release of patient info. Yadda yadda yadda.

But when I said that events like murder, mysterious deaths and patient abuse were commonplace during the time of Dick Redding’s time as a patient/inmate (I used the term “inmate,” just to rattle the cage some more), that’s when she said that she could pretty much guarantee that such things never happened at Pilgrim.

“People like to think that this place is haunted, that there are specters all over the place,” she said. “But nothing could be further from the truth. We want to put an end to those types of things, those rumors.”

At which point, of course, I pointed to documented, well reported cases of such occurrences happening at Pilgrim, as I detailed here and here.

That’s when she stammered a bit and searched for something to say.

I then asked if, around the time of Cannonball’s death, if the autopsy and processing of the body would have taken place in-house, at the hospital,or if an investigation and autopsy would have been done by Suffolk County, N.Y., officials.

She said that “at one time in our history, we did have a morgue on site, but I’m not sure when that folded.”

She asked me why I was inquiring about this man, to which I responded that Redding was a Hall-of-Fame quality pitcher and that, indeed, many are building a case for him to be inducted into the shrine. That’s when I said it. Impulsive? Perhaps? Tabloidy? Possible. Putting some accusational bait out there? Sure.

But this is journalism, folks. You want answers, you gotta stir the pot.

“I’m just concerned that if something bad did happen to Mr. Redding, there might have been a cover-up,” I said.

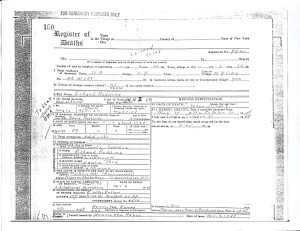

At that point, i also informed her that we, i.e. the research community, did have a copy of Redding’s death certificate, which does confirm that he was a patient at and died in Pilgrim on Halloween 1948 and that he was attended to by a doctor named “L. Kris” from May 24-Oct. 31. The cause of death, however, is whited out.

We talked for a bit more, and she ended by promising to look into it and see what she could do for me, and she also promised she’d call me back.

So that was that. In a prologue to that neat little conversation, I called the Suffolk County Police Department to find out if there would have been a PD investigation of any questionable incident at Pilgrim in 1948. The officer who answered the phone looked up Redding’s name in their database and told me they had no record of an investigation by that name.

He also said that because Pilgrim was a state facility, any outside investigation would have been conducted by the NY State Police. I thus called the public information officer at the NYSP Troop L barracks and left a message. I have yet to hear back, and I’ll keep you posted.