I hope to go into detail more about both of these soon, but here are a few interesting things I’ve discovered about a couple blackball pitchers who have captured my attention …

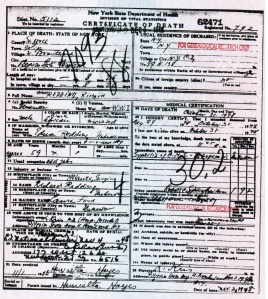

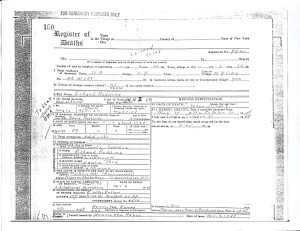

First up is Alex Albritton, to whom Gary Ashwill alerted me as part of my research into the 1948 death of Cannonball Dick Redding at a Long Island psychiatric hospital. While I initially had questions into how Redding died under reportedly “mysterious circumstances” — subsequent investigation and patience on Gary’s part revealed a death certificate that claims syphilis was the cause of death (not sure I’m buying that) — at Pilgrim State Hospital in Islip, N.Y., Gary suggested I look into the tragic death of Albritton — who pitched for Hilldale, the Philadelphia Giants and other minor teams, mainly in the 1920s — at Byberry State Hospital in Philadelphia in 1940.

Unlike the vagaries surrounding Redding’s end, the death of Albritton has never been in any doubt — he was beaten to death by an attendant whom Albritton had smacked over the head with a broomstick. I’m currently working on a story about the incident for philly.com for a sort of macabre, creepy and tragic story for Halloween.

While Albritton’s death was big news in Philly and in the black national press — how he died was never in doubt — the attendant, Frank Wienand, who was initially arrested and charged with homicide by the local coroner, was eventually cleared and absolved of all blame in the matter, thanks to a ruling that said he more or less acted in self-defense in a corrupted, underfunded hospital system for which he shouldn’t be blamed.

The insane asylum that was Byberry

During a cursory glance through history, I’ve found a few noteworthy points about “Brit.” One, the death certificate Gary, and now I have doesn’t include an official cause of death — it’s just stamped with “INQUEST PENDING.” That in itself is eerie.

Two, if we thought Pilgrim hospital was bad … apparently Byberry had an even more horrific history of abuse, torture and death. Over a matter of just a few decades in the mid-20th century, possibly over 100 violent, mysterious, sudden or otherwise unexplained deaths at the hospital. Its conditions were attributed by some government officials to poor institutional oversight and a woeful lack of funding that resulted in an insufficient amount of staff that was already underpaid.

Finally, and this could be the oddest item I’ve uncovered … according to both Seamheads.com and his death certificate, Brit was reportedly buried in Eden Memorial Cemetery in Collingdale, Penn. Eden is one of the most historic African-American cemeteries in the country, with numerous black luminaries interred there, including baseball figures Octavius V. Catto and Stanislaus Kostka Govern.

From the Eden Cemetery Web site

However, I wanted to confirm that Albritton is, in fact, buried there, and I also wanted to track down a suspicion that he, like so many Negro Leaguers, was laid to rest in an unmarked grave. But after calling the cemetery offices, a staffer there found … absolutely no record at all of an Alex Albritton interred there in 1939, 1940 or 1941. Is something fishy …?

For Albritton, you’ll have to wait until my story comes out. 🙂

OK, the other pre-integration pitcher I was to touch on is one-armed New Orleans wonder Edgar “Iron Claw” Populus, about whom I’ve written recently. Although Iron Claw was mainly a local NOLA semipro and sandlotter, his story has fascinated me, not only because of his disability, but because he flashed like a comet across the N’Awlins blackball heavens in a magical 1931 season, then seems to have largely disappeared from the local hardball scene. (I’ll chronicle that season in an upcoming post, hopefully this weekend, but I’ll see.)

But as I dug into Populus’ familial heritage, I found something perhaps even more fascinating than Iron Claw himself — his ancestry. This is something I’ll also try to go into more depth soon, but I discovered that Edgar Populus’ family tree stretches back into New Orleans history for numerous generations. While a lot of it is still muddled and unclear at this point, the Populus line, and many of its offshoots, are biracial — or, in other terms of the day, Creole or mulatto — in nature, the obvious mixing of wealthy white owners, who were probably largely French, and their slaves.

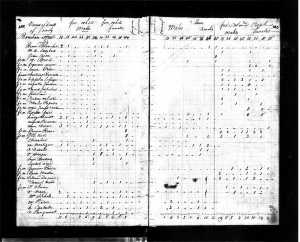

1810 federal Census report featuring one of Iron Claw Populus’ direct descendants

Edgar Populus’ line in New Orleans can be traced back at least to his great great great grandfather, Vincent Populus, who lived from 1759 to 1839. While I have yet to uncover proof that Vincent or anyone in his direct line of descent to Edgar owned slaves, it appears that many of Vincent’s early relatives were, in fact, biracial men who owned slaves themselves.

All those factors immerse local pitching great Iron Claw Populus’ ancestry firmly in the murky, complex and sometimes downright confusing racial, social and class history of perhaps the most culturally and ethnically diverse cities in the country. While I do have a cursory knowledge of that interwoven sociology, much of it is and will be new territory for me to explore down the road, and I’ll chronicle it the whole way …