Editor’s note: The following essay was written and graciously submitted by my Facebook buddy and fellow baseball historian Johnny Haynes. It’s a pretty fascinating and saddening look at how baseball, race relations and tragedy collided in May 1921 in Tulsa. I’ve only lightly edited it.

Just like the Superdome in New Orleans during Hurricane Katrina, sports venues have long borne witness to non-related pain and trauma throughout history. As baseball is the original American pastime, so too have baseball diamonds.

In 1919, McNulty Park opened for the new Tulsa Oilers of the Class A Western League and was soon a frequent destination for white major league teams and players, including Babe Ruth.

Negro League baseball had been played in Tulsa for well over a decade, and in 1920, an unnamed Tulsa team was listed as a member of the Texas Colored League. The north end of Tulsa was home to the Greenwood community, a prosperous area that housed most of the city’s Black residents.

On May 31, 1921, the white Oilers and the Oklahoma City Indians finished a doubleheader, unaware of what was happening beyond the ballpark’s walls.

One day earlier, a young man named Dick Rowland tripped walking into an elevator, accidentally landing on a white woman named Sarah Page. A bystander who heard her scream called police and he was arrested, with a sensationalized story printed in the newspaper the next day.

As the Oilers were boarding the train and the Indians were waiting for the next one, a group of armed Black residents from Tulsa who were concerned that Rowland would be lynched collided with a group of white residents at the courthouse. As the white group attempted to disarm the Black group, a shot rang out and a gun battle ensued that would envelop the entire city.

Almost simultaneously, houses caught fire, stoked by arsonists on the ground and airplanes dropping crudely made incendiary bombs. Residents who came out with their hands up were either forced back inside, shot or whisked away by civilians. Bodies were also thrown back into the burning houses, a scene witnessed by Oklahoma City players who had their train out of town delayed. Trains themselves, for that matter, were attacked, and hospitals caring for the injured stormed. The National Guard arrived and was subsequently deputized alongside “all whites” and became officially sanctioned to join the mob.

The Black residents who weren’t killed were rounded up, detained and marched by gunpoint into the city convention hall, then the baseball stadium as their homes burned. Women and children were allowed to take seats in the grandstands, while the men were held on the ballfield. None could leave until white employers came to vouch for them.

McNulty Park was photographed on that day, depicting what would look like a capacity crowd at a game were it not for the strange formation of men sitting on luggage and standing around hopelessly under armed guard. Other photographs show men being unloaded from trucks outside the stadium like cattle. The Coffeyville, Kan., Morning News described conditions in the park:

“Inside the park was color and heat – stifling, odorous heat – the crying of babies, the sound of many voices and the moaning of women; and negroes [sic] – thousands of negroes [sic] huddled together as far as the eyes could see from one end of the grandstand to the other. The majority of them accepted the inevitable in good part; crowded and hot and sticky as it was.”

Martial law was declared the following day, and perhaps because there was nothing left to burn, the riots ended.

The toll will probably never be fully accounted for. Thirty-five city blocks of homes, businesses, churches and schools were razed, resulting in a reported $4 million in property loss. An estimated 10,000 residents were homeless overnight. The Oklahoma Bureau of Vital Statistics officially reported 36 deaths, though modern estimates range from 75-300. At least 800 people were hospitalized. Predictably, only the names of the white residents who died were printed in the newspapers.

Just 10 days later, McNulty Park was back to hosting ball games, like the massacre never happened. The Tulsa Tribune advertised a doubleheader between the Elks club teams of Tulsa and Oklahoma City on June 12. Returning too would be Blackball.

On June 4, with smoke still literally hanging in the air, the Black Texas newspaper The Dallas Express announced that “the Tulsa White Sox has organized a very fast team and will be heard from soon.” The very act of forming a baseball team seems out of place given the tragedy, but it was one of the only acts of defiance left for people who lost everything.

In 1922, the Black Oilers were incorporated and were members of the Texas Colored League in 1923 and 1929, spending most of their time in independent ball. One of the teams the Black Oilers would host in late September 1922 would be the Wichita Monrovians, who would take on and outplay the Ku Klux Klan’s team in Wichita.

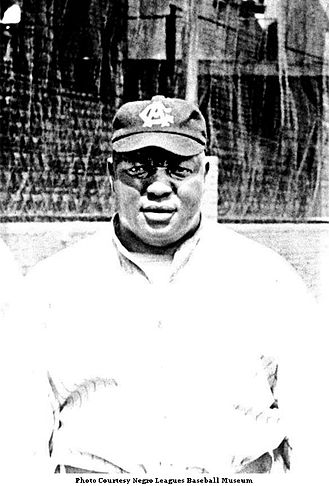

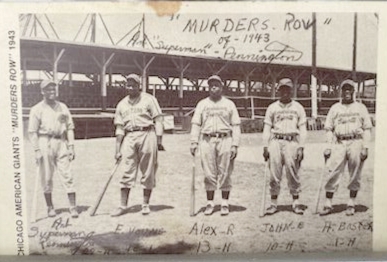

In 1925, the Chicago American Giants and Kansas City Monarchs were juggernauts of the still young Negro National League when they linked up for a three-game set in Tulsa from Aug. 19-21. Despite receiving no compensation from insurance or otherwise, the Black residents who stayed did their best to rebuild, and seeing two big league teams was a welcome distraction.

The games coincided with the 26th annual convention of the National Negro Business League, a meeting of Black entrepreneurs and businessmen from across the country. “The games played at Tulsa, Okla … between the American Giants and Kansas City, will not count in the official standing,” reported the Chicago Defender. The Tulsa Tribune stated the opposite in their advertisement of the game.

Negro National League founder and American Giants owner and manager Rube Foster was not unaware of what happened in late spring 1921 at the ballpark. The “Red Summer” that saw violence occur in 26 cities across the country, including Chicago, precipitated the formation of the NNL in 1920. For Foster, a calculating man who had a reason for every single thing he did, the decision to visit Tulsa was likely formed by several things. For one, it was an opportunity to flex for Negro League baseball, which was quickly becoming the largest Black business in the United States, to other business owners.

The NNL teams’ appearance at McNulty also seemed cathartic and offered both healing and an act of defiance in a city where so much sadness and buried anger still lingered. For the Monarchs’ future Hall of Famer Bullet Rogan, the game was a homecoming of sorts – Rogan spent his childhood in Oklahoma City.

In the opening game of the series, the Monarchs routed the American Giants, 10-4, on long home runs by George Sweatt and Newt Allen. Game two went to the Monarchs again in a 13-9 slugfest, reported in the Enid Daily Eagle. No score has been found yet for the third game.

The American Giants would finish just behind the Monarchs in the NNL standings in 1925, who would go on to win the league pennant over the St. Louis Stars but lose the Negro World Series to Hilldale, five games to one. Several Black teams would subsequently call Tulsa home, including the Black Oilers, T-Town Clowns and Tulsa White Sox.

Just a few years after the massacre, in 1929, McNulty Park was torn down and replaced by a grocery store. Today, a Home Depot parking lot sits on the site.

This story, however, underscores a few things. This history still must be taught, beginning to end. I’ve considered myself a longtime baseball fan and history nerd but never knew any of this story. The Greenwood Massacre is required teaching in Oklahoma schools as of 2020, but not anywhere else.

If the white players who were playing at the time were shaken by the terror they witnessed, then one can imagine that the Black players who just lost their homes, businesses and livelihoods faced even more unfathomable heartbreak. And yet, as generations of Black players would do in the face of oppression, they played ball anyway.

Editor’s note: If anyone else would like to submit something for publication on this blog, definitely feel free to emails me at rwhirty218@yahoo.com. Thanks, and special thanks to Johnny Haynes for today’s post!