This is a fairly short follow-up post to my previous ones (here and here) about John Bissant, his family and his grave in New Orleans’ Carrollton Cemetery. …

There’s been some confusion and lingering question marks about a few details in John’s life, and I wanted to maybe clear some of them up by connecting once again with Charisse Wheeler, Bissant’s granddaughter.

I chatted once more with Charisse, this time via text, a week or two ago and posed her a few questions, the first being about the specifics of John’s burial situation. Given that he, like just about all other people of color in New Orleans for centuries, was relegated to a segregated, “colored” section of burying ground in death, the current circumstances of his final resting place are somewhat frustrating and, honestly, depressing.

The little corner of Carrollton Cemetery carved out for African Americans is filled with ramshackle graves, fading and falling tombstones, and weeds and overgrown grass. When it rains, the plots are frequently muddy and difficult to access. Such is the result of the social and economic conditions rendered by the repressive, unjust system of Jim Crow.

To that end, Charisse told me that there are Bissants scattered all through the sectioned-off area of Carrollton Cemetery, and some of the family graves include more than one person. That includes athletic legend John Bissant, who died in Houston in 2006 and who’s interred with his wife (Charisse’s grandmother), Delores (died 1994), and his daughter (Charisse’s aunt), Barbara (died 2018).

The grave lacks a sufficient stone or marker, a situation Charisse and her relatives are working hard to remedy. (I’m hoping to see if the grave can be a future project of the famed Negro League Baseball Grave Marker Project as well.)

The second question I brought up with Charisse was the confusion I had when looking through old newspaper archives Ancestry because I discovered a bunch of John Bissants scattered through the various records, including multiple “Junior” and “Senior” monikers.

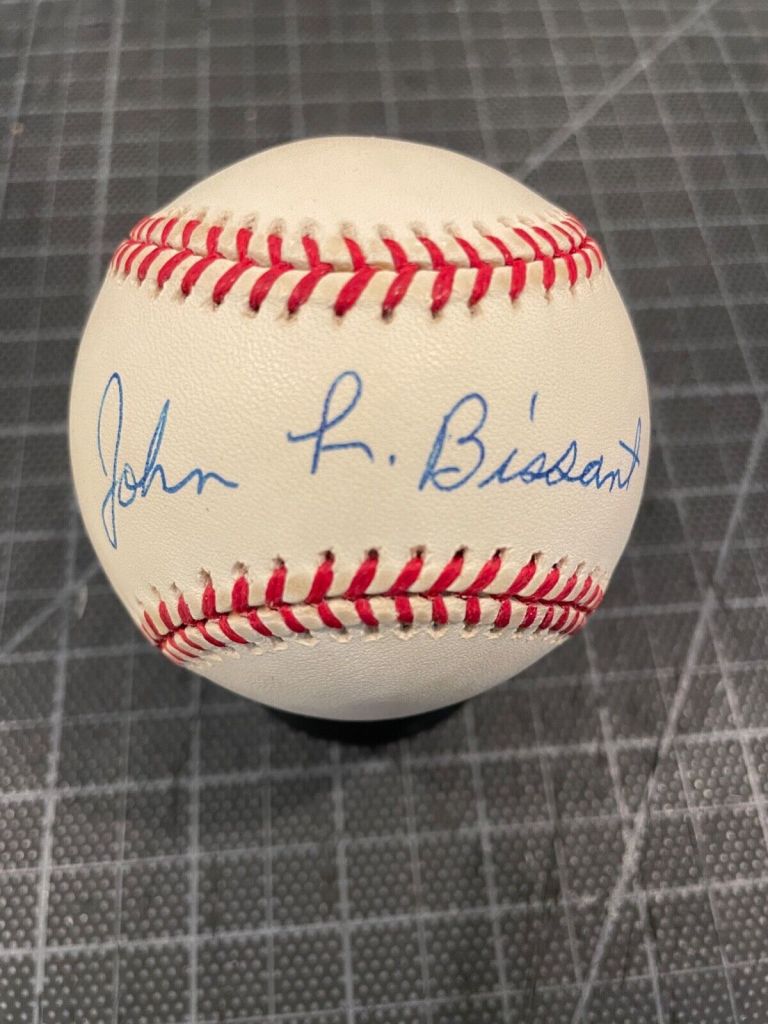

That perplexity led me to ask Charisse about the succession of John Bissants in New Orleans and which one was which. It turns out the John Lawrence Bissant of Negro Leagues lore is John L. Bissant Jr., son of John L. Bissant Sr. and father of (technically) John Bissant III.

However, in the 2006 Times-Picayune obituary of baseball great John Bissant, he’s referred to as John Sr., and his son is listed as John Jr., even though technically John the Chicago American Giant is himself John Jr., and the man listed in the obit as John Jr. is actually John III.

Charisse said that for some reason, when the actual John Sr. passed in 1957, the family began calling Charisse’s grandfather/baseball great John Sr. and began addressing John III as John Jr.

Confused? I sure was. And while such details might seem like relative minutiae, they’re actually quite important when doing historical research, which often on paper doesn’t reflect individual family traditions and quirks that can cloud the record.

The third topic on my mind is one that’s puzzled me, as well as other Negro Leagues aficionados (including my pal James Tate, who’s queried several times about it), is the relationship between John Bissant (the star athlete one) and Bob Bissant, who also played some pro and semipro baseball and was quite the athlete himself.

Bob, an infielder, played locally in New Orleans for a slew of teams, beginning in the 1930s with the Algiers Giants, a longtime team based across the river on the eastbank of the city; the Jax Red Sox, operated by businessman and baseball magnate Fred Caulfield; the New Orleans Athletics; and that famed peculiarity of a club, the Zulu Cannibal Giants, they of facepaint and grass skirts. In the 1940s he also captained the Black Pelicans, and coached the Houma Red Sox (the town of Houma is located about an hour southwest of the Big Easy).

Bob graduated from the local sandlots and ballfields to, like John Bissant, spend some time on teams near the upper echelon of professional Blackball, including the Nashville Cubs; the Miami Ethiopian Clowns; and, in the ’40s, the Baltimore Elite Giants of the second Negro National League. At the time, the Elites were managed by New Orleans baseball guru Wesley Barrow. (To clarify, however, media reports from early 1947 stated that Barrow had signed Bob up to play for Elites that season, but Bissant isn’t included on the Seamheads database’s roster for the Elites from that year.)

Bob Bissant also played a year or two in 1930s on a team that barnstormed in Canada, and in 1946, ventured to the Pacific Northwest to join the Portland Rosebuds of the ambitious but short-lived West Coast Negro Baseball League. The Rosebuds were owned by Olympic legend Jesse Owens and managed by none other than Wesley Barrow, whose presence undoubtedly helped convince Bob to go to Oregon.

Like many of his Negro Leagues peers in his hometown, Bob Bissant was quite active with the Old Timers Baseball Club of New Orleans, as much or perhaps more than John was, attending the banquets and honor ceremonies. He played in several of the group’s annual reunion all star games at Wesley Barrow Stadium, and in 1980, the club honored him as veteran player of the year.

Bob Bissant died in 1999 at the age of 85 and was interred at Providence Memorial Park and Mausoleum in the neighboring suburb of Metairie.

Because of Bob’s heavy involvement in the Black baseball, both as an active player and a retiree, I frequently came across references to Bob Bissant when going through the microfilmed archives of the Louisiana Weekly’s sports section. Since Bob and John were close in age and mentioned in newspaper coverage in the same time period, I’d assumed that Bob and John were brothers.

However, as I just learned from Charisse, that assumption was incorrect. Turns out they’re actually first cousins – their fathers (John Sr. for John and Champ Bissant Sr. for Bob) were brothers.

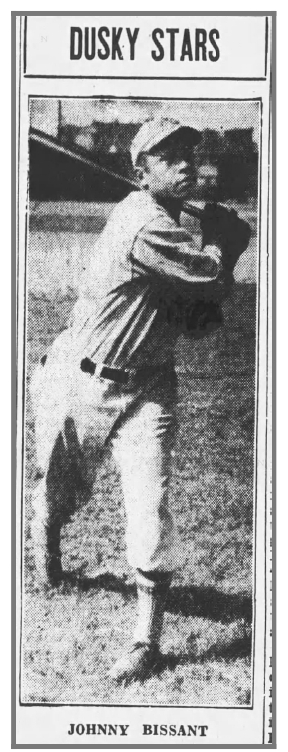

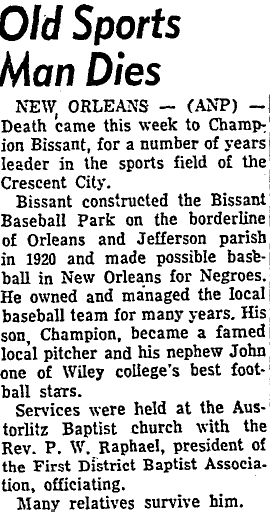

And there’s another facet to this familial tale – one of Bob’s brothers (and another first cousin for John Jr.), Champion Bissant Jr., also played a little ball here and there, mostly as a pitcher,meaning there were at least three Bissants who laced up cleats and took to the athletic fields. On top of that, too, Champ Jr.’s and Bob’s father, Champion Sr., was also a key player in the New Orleans Negro Leagues scene, owning and managing the Bissant Giants, whose homefield was Bissant Baseball Park, which Champ Sr. built on the Orleans/Jefferson parish line.

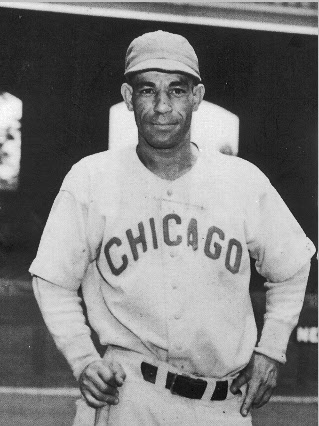

Finally, Charisse shed some light on the relationship of John Bissant and Lloyd “Ducky” Davenport, another native New Orleanian who made good in the Negro major leagues, especially, like John, with the Chicago American Giants.

Ducky (whose own anonymous grave is another sad tale on its own) was born in the Big Easy in 1911 and died in 1985. Like John Bissant, he played on local teams before landing gigs in the majors, beginning with Ed Bolden’s Philadelphia Stars of the second Negro National League.

He eventually enjoyed significant stints with the Cincinnati Tigers, Memphis Red Sox, Birmingham Black Barons, Cleveland Buckeyes (including the 1945 season, when the Bucks won the NAL pennant and the Negro World Series) and Chicago American Giants (including the 1943 campaign, when he led the club in batting at .313), all of the Negro American League.

(Davenport’s time with the Black Barons is perhaps the most interesting, at least to me. Ducky played for Birmingham during the 1941 and ’42 seasons; during the former year he came off the bench, but in 1942 he started in the outfield. The Black Barons at the time were managed by Louisiana legend Winfield Welch, a Napoleonville, La., native who managed several New Orleans and Louisiana clubs before hitching up with the Barons. While in Birmingham, Welch set up an informal but productive pipeline of talent from the New Orleans area up to the Black Barons; among those players, besides Ducky, was J.B. Spencer, from the NOLA suburb of Gretna, who later played for some of the dynastic Homestead Grays teams. Spencer was on the Black Barons roster at the same time Davenport played with Birmingham.)

Davenport was also selected to play in six East-West All-Star Games, and multiple North-South All-Star Games (which were held in NOLA and organized by legendary local entrepreneur and baseball magnate Allen Page). Ducky also spent a little time in the Mexican League.

Over parts or all of 10 seasons, largely as an outfielder, in the Negro majors, Ducky – who also earned the moniker of “Bearman” Davenport in Crescent City baseball circles – appeared in 242 games and batted a quite respectable .291, along with a .350 on-base percentage, .377 slugging and .726 OPS, all according to Seamheads. He has slashed 46 doubles, clubbed 11 triples, tallied 91 RBIs, swiped 30 bases and posted a WAR of 65.0. He batted and threw left.

Davenport was a relatively small guy, too; he was 5-foot-6 and 155 pounds, and he reportedly waddled when he walked, hence his nickname.

Most pertinent to this post, though, is the large amount of time Davenport and John Bissant spent with the same teams and on the same rosters; the pair was practically joined at the hip during their careers.

In 1937, John and Ducky both played for the Double Duty Radcliffe-managed Cincinnati Tigers (along with pitcher Eugene Bremer and, briefly, Lionel Decuir, both also from New Orleans), and, most prominently, they reunited on the 1943-44 Chicago American Giants, with both New Orleans lads starting in the outfield.

Bissant and Davenport were extremely close their entire lives, Charisse told me. She noted that the two baseball stars became friends in New Orleans when they were 8 or 9.

“Ducky was [John’s] best friend,” Charisse said.

She said Ducky was a familiar face for the Bissant family, including Charisse.

“He’d always be at our house when I was growing up,” she said. “They were very close and stayed in touch until Ducky died [in 1985].”

The entire time, she added, baseball was never far from the friends’ minds.

“I loved to hear them argue and tell their stories about baseball,” Charisse said.

She added, “[Davenport] actually lived in my grandparents house, in a separate house, for a while.”

But what about Davenport’s famous nickname? Where did it come from, I asked Charisse.

She said she’s not sure how the moniker started, but she and her whole family just always knew him as Ducky.

“It just stuck with him over the years, even in baseball,” Charisse said.

She added: “My mom said that when she was a little girl, that’s all everyone ever called him.”

(It’s worth noting, though, that in his 1994 article about Davenport, Lewis asserted that Ducky walked with a sort of waddle, and, at a scrappy 5-foot-four and 150 pounds, Davenport indeed looked like a waterfowl when he patrolled the outfield during his career.)

I’ve blogged a little bit about Ducky Davenport, in particular about the sad situation with his grave – he was buried at Holt Cemetery, New Orleans’ primary potter’s field. And not only does Ducky not have a grave marker or headstone of any sort, no one is sure where his grave even is in Holt.

That’s about all for this time, but I’m going to try to have one more John Bissant post coming soon!