Editor’s note: I recently wrote an article for The Louisiana Weekly newspaper here in New Orleans about the very last Negro League World Series, which was held in 1948. One game of the series was played in the Crescent City, with legendary businessman and sports promoter Allen Page organizing and hosting the event.

For my article, I got a few thoughts from Rodney Page, Allen’s son, and he generously agreed to do so. I used some of his comments for my article, but I wanted to show people the entirety of the amazing few paragraphs he put together about the 1948 NLWS, and his father’s role in baseball history. Here are those full comments. Many thanks to Rodney for his work.

Seventy-five years is a long time to honor and celebrate a significant event. Seventy-five years also coincides with a “diamond jubilee,” which resonates with the Negro League World Series of 1948. One of those World Series games was played on the Pelican Stadium baseball “diamond” in my hometown of NOLA.

Another connection is that I was born 75 years ago (Sept. 4, 1948) in NOLA at Flint-Goodridge Hospital, located at the corner of Louisiana Avenue and Lasalle Street.

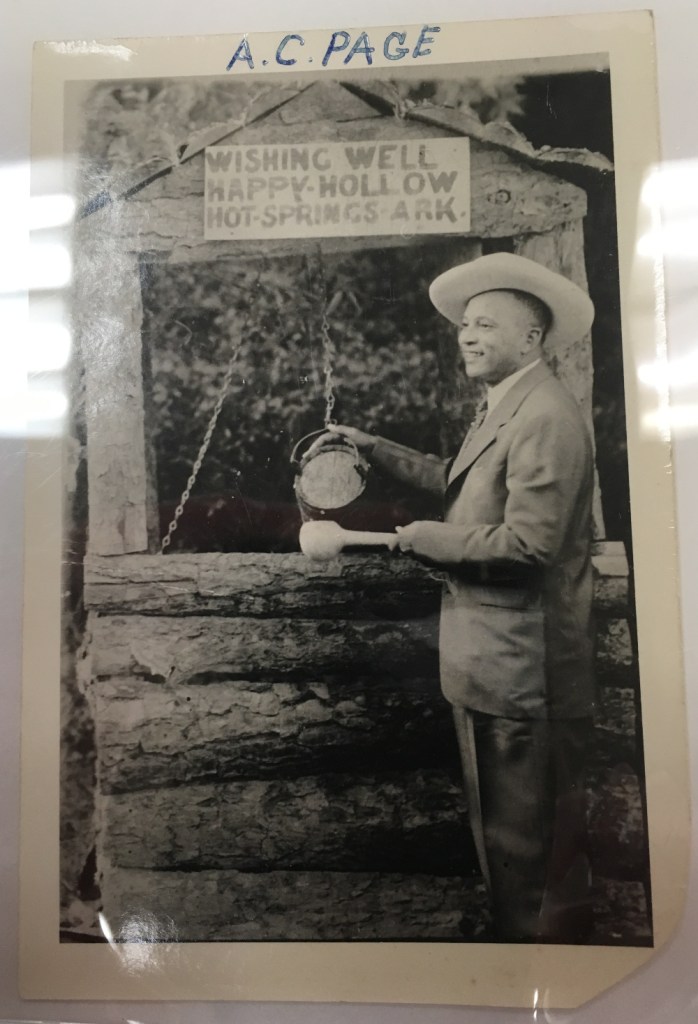

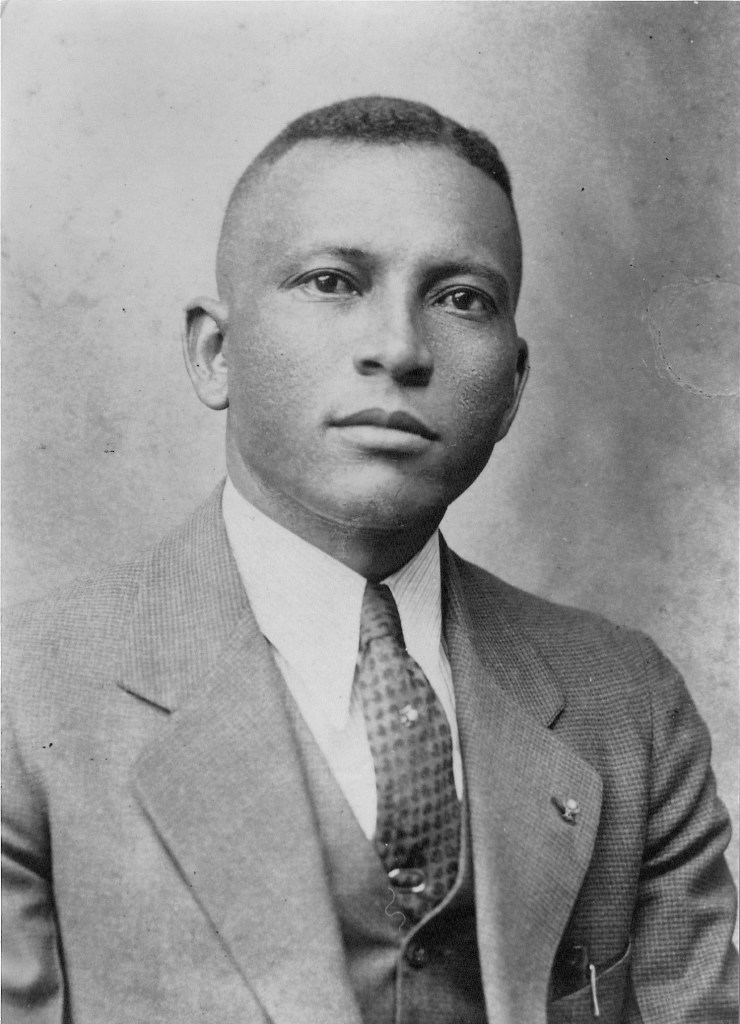

The host and promoter of this World Series game in 1948 was my father, Allen Page. This is a testament to his significant contributions to the entire Negro Leagues baseball experience. His contributions were not just local in NOLA, but included regional and national affiliations, promotions, and endeavors. The 1948 Negro World Series is an example of that. Consider the risks and the connections necessary in bringing this showcase to NOLA.

The hero’s journey does not always end in resounding victory. Sometimes the reward, the victory, is in the process. The process of overcoming and transcending enormous challenges and obstacles. The societal changes from segregation to integration and all of the gains, and losses, of this shift in the social landscape of America. From my perspective, this is part of the deeper story of the Negro Leagues, and Allen Page.

The true story of Allen Page is his indomitable spirit, which speaks to the heart of self-reliance, self-definition and self-determination.

Rodney Page

Some say this was the last Negro Leagues World Series, as Black baseball’s decline was rapidly approaching due to the integration of MLB. An interesting pattern is apparent in the journey of Allen Page. The final resting place for the once outstanding St. Louis Stars and the Newark Eagles was in NOLA.

In addition, one of the final NLWS games was played in NOLA. Allen Page was in the midst of all three significant events in the rich history of Negro Leagues baseball.

In my eyes, my father is a hero. Knowing where he came from and what he accomplished has given my life enormous inspiration and pride. He dared greatly and risked often and much. The true story of Allen Page is his indomitable spirit, which speaks to the heart of self-reliance, self-definition and self-determination. He transcended and excelled despite the shackles of the Jim Crow South and overt racism in America. A legacy of firsts was in his DNA.

Rodney Page, Sept. 14, 2023