Another follow up on the life, career and legacy of John Bissant, Negro Leagues great and arguably the greatest all-around athlete New Orleans has ever produced. For some earlier posts, check out this, this and this.

In this post I want to kind of outline a little more about John’s athletic career, which, when reviewed from modern times, is pretty incredible. Aside from his baseball achievements and exploits, Bissant, who was born in 1914 in New Orleans, excelled on the gridiron, on the hardwood and on the cinders, first at historic McDonogh 35 High School in New Orleans, then the Texas HBCU Wiley College, and then on numerous professional and semipro football and baseball teams across the country and in this city.

John Bissant’s talent and achievements stemmed from his status as a well rounded, multi-tool athlete whose abilities were adaptable for just about any sport. Whatever you asked him to, he could do it, beginning with his fleetness afoot.

One facet of Bissant’s athletic prowess was his speed, for example, and he used it, perhaps most obviously on the cinders and on the gridiron, to his and his team’s advantage. Articles from his time with the Chicago American Giants, as well as other teams, often report that he occasionally took part in foot races on the field as a side attraction at games.

For instance, a May 1943 article in the Cincinnati Post that previews a Negro American League doubleheader between the American Giants and Cincinnati Clowns reported that Bissant was slated for a 100-yard sprint showdown with members of the Clowns:

“Johnny Bissant, Chicago outfielder, is generally regarded as the fastest man in Negro baseball, but the Clowns dispute this, claiming that their own Reece (Goose) Tatum, Freddy Wilson and Charley Harris can match strides with anyone.”

The Clowns swept the doubleheader, but it’s unclear who won the races, if they were run.

As a side note, the teams also held a “slowest player” race, with Baton Rouge fella Lloyd “Pepper” Bassett, aka the Rocking Chair Catcher, at the time with the Cincinnati Clowns, as a favorite in that one.

Contemporaneous media reports frequently mentioned Bissant’s fleet feet in the outfield, where he chased down fly balls and flashed the leather frequently. In July 1941 a newspaper in Medford, Ore., called him “the club’s speed merchant” and that Bissant was paired in the Giants’ outfield with close friend Ducky Davenport, “another streak of lightning,” while In June 1942, a paper in Benton Harbor, Mich., noted that Bissant “holds several sprint championships and is one of the fastest negro [sic] players in the national pastime,” while a July 1944 article in the Belleville (Ill.) News-Democrat called Bissant “the team’s ace outfielder, and is a hard hitter as well as a great ground-coverer.”

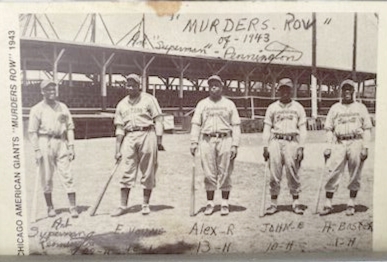

As an outfielder, Bissant had the good fortune to team with other standouts – including NOLA lad Davenport – to form fearsome lineups in the outer garden for the American Giants. In June 1943, an Illinois paper noted that Bissant and Davenport were joined by Art Pennington in an “outfield [that] is considered the best in the [NAL].”

The South Bend, Ind., Tribune, in previewing a game between Bissant’s Chicago Brown Bombers and a northern Indiana semipro team, offered a concise but glowing estimation of the New Orleans legend. At the time Bissant was usually stationed in left field.

“Bissant is tagged as the fleetest of the Bombers’ outfield,” the newspaper stated. “Because of his fleetness he sometimes patrols center giving the Bombers added protection on the strength of Bissant’s ability to roam into right or left to haul down apparent hits. He is death on [the] bases and specializes in base thievery to the chagrin of rival catchers.”

Actually, during and after Bissant’s playing career, newspapers often referred to Bissant together with Ducky Davenport as a duo of greatness; because both of them were from New Orleans – they competed against each other in high school here – and were both speedsters who prowled the outfield for the American Giants, it was natural to mention both in the same breath.

However, even then, Bissant garnered the highest praise, partially because he was so well rounded as an athlete.

“Bissant was a natural, as was Davenport,” stated the Louisiana Weekly in April 1970, “but [Bissant’s] wonderful physique, speed and power gave him the advantage, and his best sport was probably football, although he lettered in track [and] basketball, as well as baseball and football.”

As a result of his completeness as a player, his athletic glories were many. A few of Bissant’s accomplishments, honors and activities as a pro baseballer:

- Played in the 1945 East-West All Star game in Comiskey Park in Chicago. (I should note that I couldn’t find any solid evidence that he actually appeared in the game.)

- Starred at historic McDonogh 35 High School, from which he graduated in June 1935. McDonogh was the first four-year public high school for African Americans during the first half of the 20th century, and it boasts several pro athletes, as well as groundbreaking politicians and Civil Rights activists, including Ernest “Dutch” Morial, New Orleans’ first mayor of color; Joan Bernard Armstrong, a racial and gender trailblazers in the Louisiana state court system; and Rev. A.L. Davis, a founder of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

- Broke into the Negro League majors in July 1937 with the Cincinnati Tigers of the Negro American League, managed by Double Duty Radcliffe. Bissant only played a handful of games for the Tigers after being lured away from the New Orleans Black Pelicans; during this brief stint in the Queen City, John was teammates with fellow Louisianans Ducky Davenport, Gene Bremer and Lionel Decuir. The Tigers themselves had folded by the end of the ’37 season.

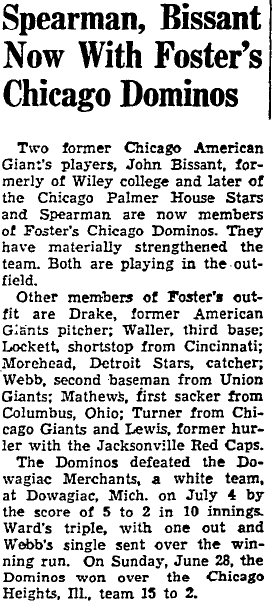

- Apparently defected briefly from the American Giants to suit up for an extremely short-lived, largely barnstorming semipro team, the Chicago Dominos (or Dominoes), in summer 1942. According to media reports, the club was owned by one Jimmy Foster, managed by Harlem Globetrotters impresario Abe Saperstein, and composed of guys who decided to work in factories in the wartime defense industry.

- Apparently shared/alternated managerial duties of Chicago American Giants in 1944 with fellow New Orleanian Ducky Davenport and the great, severely underrated Bingo DeMoss. It should be noted that Bissant also served as team captain in 1947-48 under manager Candy Jim Taylor.

- Selected for the South team seventh annual North-South All-Star Game at Pelican Stadium in New Orleans in October 1946.

- Played in another contest billed as a “North-South all-star” game with two picked nines from the NAL ranks; New Orleanian Bissant was slated to play for the North team, ironically. The game was scheduled for Hudson Field in Dayton, Ohio.

- Played in charity fundraising games in New Orleans, including at the Times-Picayune newspaper’s Christmas Gift Fund all-star game in 1947. Also taking the field were fellow local guys Herb Simpson and Wesley Barrow.

- Honored by the Crescent City Old Timers Baseball Club in 1970. The Old Timers Club was a New Orleans institution that brought together former Negro League players and managers from New Orleans and Louisiana for 20-plus years. Bissant was a regular member of the organization.

- Served as an instructor at the Old Timers Club at the group’s youth clinics in the 1970s..

- Selected for the National Black Sports Foundation Hall of Fame, probably in 1975.

- Invited by the Atlanta Braves to be honored at the team’s 1997 Negro Leagues reunion and recognition event for “Black Living Legends of Negro Baseball.” Also in attendance was Herb Simpson.

In a review of his career, here’s what I came up with, across several sources, in terms of some of the teams with whom Bissant played over the years:

- Caulfield Ads (?) (1934) — The semipro Caulfield Ads were owned and managed by Fred Caulfield, a businessman in New Orleans who was extremely active in Black baseball in the city beginning in the late 1910s and running through the ’40s. What media coverage I’ve found about the 1934 Ads (which is very little) only lists the last name of “Bissant,” with no first name given. That leaves open the possibility that it could be John’s uncle, Champ Bissant, or his cousin, Bob Bissant. If the player listed is indeed John Bissant, it would mean that he was still attending McDonogh 35 High School at the time.

- Cole’s American Giants (1934), a post-Rube Foster iteration of the club owned by Robert Cole and Horace Hall and piloted by holdover manager and Rube disciple Dave Malarcher. The team was part of the second Negro National League at the time, winning the first-half league title but losing the championship series to the second-half-winning Philadelphia Stars. However, although Riley states that Bissant was on this club, Seamheads doesn’t include any record of him for the season.

- Shreveport Acme Giants (1935-36), a largely barnstorming team loosely based in the city of Shreveport in northwestern Louisiana. The history of the Acmes is quite fascinating and worthy of its own detailed chronicling. The team was managed by Louisianan Winfield Welch, whose career spanned several decades and included piloting several teams in the New Orleans area, the Alexandria Black Aces, multiple Shreveport teams, the Cincinnati Crescents and, most prominently, the big-league Birmingham Black Barons, whom he guided to two Negro American League pennants. Anyway, at this time in question, the Acme Giants included several guys from New Orleans and Louisiana, as well as the one and only Buck O’Neil, who was just beginning his career in pro baseball and used the Acmes as a launching pad for bigger and better things. The team toured up into the Midwest, the northern Plains and into central Canada; some of its members, including a few New Orleanians, ended up hopping to Canadian teams, while others ended up with the Cincinnati Tigers of the mid-to-late 1930s. (I should note that I wasn’t able to confirm that he definitely did play for the Acmes, but that by no means he absolutely didn’t.) And on that note …

- The Cincinnati Tigers (1937) of the NAL (see aforementioned discussion of this team). Bissant jumped to the Tigers in July 1937 from the American Giants.

- The New Orleans Black Pelicans (1938).

- Caulfield Red Sox (1938) — Another one of Fred Caulfield’s clubs.

- Shreveport Black Sports (1938). I found a bunch of articles referring to them, including, for example, one from the Longview (Texas) News-Journal newspaper from May 1938 that reported that Bissant swatted a three-run home run to help the Sports stake a 3-2 win over the Fort Worth Black Panthers. The Black Sports were also managed by Winfield Welch and were members of the Texas Negro League. It makes sense that Bissant would play for a team based in Shreveport because Wiley was only roughly 65 miles from the Louisiana city in Marshall, Texas, making it easy for Bissant to play for the Sports during summers out of school.

- Chicago American Giants (1939).

- Birmingham Black Barons (1940).

- Chicago American Giants (1941-48). The CAGs frequently played exhibition or spring training games in New Orleans. In the 1940s the Giants were well past their prime years that included their founding and early ownership by Rube Foster in the 1910s and ’20s, and later owner Robert Cole in the 1930s. In the 1940s the club was owned by J.B. Martin, who also served as a league executive in the second Negro National League and the Negro Southern League and as president of the NAL while he owned the Chicago American Giants. As far as Bissant goes, it’s important to note that while his overall tenure with the American Giants spanned nearly a decade, his time with the CAGs wasn’t one continuous stretch; he frequently jumped to other teams here and there, as this piece will show.

- Chicago Palmer House Stars (1940-43), a barnstorming team that won three straight Illinois state semipro championships, and they took part in the National Baseball Congress World Series in Wichita, Kan., and the Denver Post tournament, both annual events to determine national semipro champs. The Palmer House is a historic downtown Chicago luxury hotel that, in the 1930’s and ’40s, sponsored several baseball teams, including one African-American one. The hotel was owned by Potter Palmer III; the Stars baseball team itself was owned by L.M. Gamble, and, during its most successful stint, it was managed by Alex Radcliffe, the brother of the legendary Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe and a player and pilot with a very distinguished record of his own. It appears Ducky Davenport was also on the roster at certain points. The team was referred to in different ways in the media; sometimes they were called the Chicago All Stars, or the Chicago Colored All Stars. (The lack of consistent naming definitely muddies the historical record and can be very confusing. For example, I wouldn’t rule out one or more of these various monikers actually representing different teams, or at least variations of the Palmer House club.) The Palmer House Hotel is still in operation today as a Hilton property. For more detailed info on the Palmer House Stars, check out this excellent article by Leslie Heaphy.

- Chicago Brown Bombers (1942-43?) of the very short-lived, somewhat half-baked Negro Major Baseball League, the “brainchild” of white team owners/promoters Abe Saperstein and Syd Pollock. The league only lasted for a season, with few records and no standings left behind. The Bombers were managed in 1942 by Bingo DeMoss and owned by L.H. Gamble; they might actually have evolved from the previously listed Palmer House team. (Another version of the Brown Bombers played in the United States League in 1945; the USL was created by Gus Greenlee and Branch Rickey as a stealth way to evaluate Black baseball talent and bring players into Organized Baseball.) As far as Bissant is concerned, he appears to have started the 1942 season with the Bombers, defecting from the Palmer House club that he played for the previous year. However, in the middle of the 1942 campaign, he jumped to the next team listed below. Then found articles on the Brown Bombers from May 1943 that previewed the upcoming season, but it’s unclear how many games the Bombers played in ’43. The articles do list Bissant as an outfielder on the team still, but I couldn’t find an actual box score from early 1943 that proves that Bissant actually did take the field for the Bombers in 1943. What is certain is that by the early summer of ’43, Bissant was back in the fold with the Chicago American Giants.

- Foster’s Chicago Dominoes (1942). A July 1943 article in the Chicago Defender states that Bissant, “formerly of Wiley college [sic] and later of the Chicago Palmer House Stars,” had recently signed on with the Dominos. The Dominoes seem to have offered a fair amount of clowning at games; one newspaper called them a “razzle-dazzle” club who “display a brand of baseball akin to the basketball gyrations of the colored Globe Trotters [sic], stablemates of the Dominoes and piloted by Abe Saperstein.” It appears that Bissant finished out the rest of the ’42 schedule with the Dominos. Overall, chronicling Bissant’s exact pathway through the early 1940s is extremely difficult, because he jumped around a lot, at least before ending up back with the American Giants in mid-1943.

- Kohlman All Stars (1947), a New Orleans semipro team. By now Bissant was well past his prime and apparently picking up baseball action where he could, largely in the Big Easy. The Kohlmans were managed by legendary New Orleans player/manager Wesley Barrow, and the club also included fellow local lads Herb Simpson and Billy Horne, both one-time Chicago American Giants as well. In October 1947 the Kohlmans welcomed an all-star team from McComb, Miss., for an exhibition fundraiser to benefit the Times-Picayune Christmas gift fund.

- New Orleans Creoles (June 1948) of the Negro Southern League.

- New Orleans Black Pelicans (1955). Also on the roster were Bob Bissant, Robert “Black Diamond” Pipkins and Morris “Tar Rock” Arthur.

That listing is by no means complete, especially when it comes to Bissant’s presence on local New Orleans teams both before and after his time in the Negro Major Leagues. The best source for such info is the Louisiana Weekly, but a complete run of the paper’s archives isn’t available on any databases, and it’s been difficult getting to libraries that do have a complete run on microfilm.

Now, although best known on a national scale as an accomplished baseball player, it’s necessary to emphasize the fact that Bissant was a multi-sport star, also excelling in basketball, track and especially football.

Bissant’s greatest success on the gridiron came at Wiley College, a small, liberal-arts HBCU located in Marshall, Texas. Founded in 1873 – just eight years after the end of the Civil War – by the Freedman’s Aid Society of the Methodist Episcopal Church. Wiley, known today as Wiley University, has been known as one of the best and oldest HBCUs west of the Mississippi. Today, its enrollment tallies about 1,100.

Wiley students played a key role in the development of the Civil Rights Movement in Texas; together with students at the now-defunct Bishop College, another HBCU located in Marshall, Wiley students organized and participated in the first sit-ins protesting segregation in the Lone Star State. In addition, one of the national Civil Rights Movement’s most esteemed leaders, James Farmer, graduated from Wiley.

The Wiley varsity football team, meanwhile, used to be a regional HBCU powerhouse; Wiley helped co-found the Southwestern Athletic Conference and claimed 10 conference titles between 1923-57 under legendary head coach Pop Long.

Unfortunately, the Wildcats no longer have a football team, and in the years since their pigskin glory days, the school was dropped out of the SWAC in all other sports and is now a member of the Gulf Coast Athletic Conference, which includes smaller schools competing in the National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics (NAIA).

However, at a time when Wiley did have a pigskin program, John Bissant shined for the Wildcats on the field for several years. He arrived in Marshall for the fall 1935 semester and while he logged a fair amount of action during his freshman season, it was his second year in 1936 that really saw the Bissant legend start to grow at Wiley.

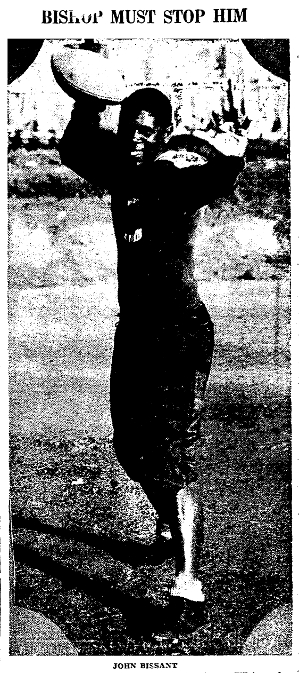

Tipping the scales at a compact 167 pounds, give or take a couple, John became a fixture in the starting lineup at right halfback, piling up yards and touchdowns. In addition to carrying the rock, Bissant was also adept at both slinging and receiving the ball. (The sport looked somewhat different in the late 1930s, when the modern concept of a quarterback hadn’t yet developed and a dizzyingly diverse ground game remained the foundation for most college offenses.) Bissant could also placekick on extra points or field goals, as well as snare interceptions on defense at a time when most college teams featured numerous two-way players.

The 1937 season witnessed John staking out a permanent spot at or near the top of the SWAC statistical rundowns, leading the conference in scoring at various points. At the end of the ’37 campaign, nationally syndicated columnist James Parks listed Bissant at halfback on Parks’ postseason HBCU All-American team.

The 1938 season was Bissant’s senior year, and by the end of things he was one of the most lauded, most successful halfbacks in the HBCU football world. He was the SWAC’s leading scorer for ’38, and at the end of the campaign he was named to multiple first-team All-SWAC and All-America lists, including James Parks’ as well as that of Randy Dixon, another popular national Black media journalist who called Bissant the best all-around back in the game.

Quite interestingly, John Bissant garnered the nickname “Geech” or “Geechie” while playing at Wiley, although it’s not clear how he garnered that sobriquet. John’s granddaughter, Charisse Wheeler, told me that she’d known about his nickname, but she wasn’t sure where the moniker came from.

Word of John’s gridiron prowess traveled well, and his services were sought after as both a coach; he was an assistant coach for Florida A&M in the 1939 Orange Blossom Classic, an annual HBCU football bowl game, for example. Later on, in 1948, Bissant served as an assistant coach for the New Orleans Delta Midgets, who were likely another local semipro squad.

John also played semipro football himself at various times in his athletic career, including local NOLA clubs like the New Orleans Pirates in the late 1930s/early 1940s, and the Southsiders, one of the teams that made up the New Orleans Negro Independant Football League later in the 1940s.

Bissant also hit the gridiron for the Chicago Brown Bombers football team in fall 1940. Actually, it appears that he might have caught on, or at least connected, with the Bombers when the Windy City aggregation came to New Orleans to play the Pirates.

Given that he had a reputation as a speed demon, John also ran track in high school and for the Wiley Wildcats, often competing in the relays. At the 1939 Tuskegee Relays, for example, he ran legs of the 440-yard and 880-yard relays.

Strangely enough, I haven’t been able to see any definitive evidence that Bissant played for the Wiley baseball team. I’ve reached out to the special collections department at the Wiley library a few times but haven’t heard back.

Anyway, after retiring from baseball, John Bissant worked at several jobs in the New Orleans area, including at NASA’s Michoud Assembly Facility; Lykes Brothers Steamship Company, a shipping business; Glazer Steel and Aluminum; and a security guard firm.

John Bissant died on April 1, 2006, in Houston, Texas, at the age of 92; he had evacuated to Houston from New Orleans because of Hurricane Katrina. In its obituary of Bissant, the Times-Picayune called him “a Negro League Baseball Legend.”

Hopefully someday we can persuade the Greater New Orleans Sports Hall of Fame and/or the Louisiana Sports Hall of Fame to induct John Bissant. Right now both halls of fame each have several inductees from the Negro Leagues, but so far Bissant isn’t among them.