Editor’s note: More than two years ago, I wrote this article for The Louisiana Weekly newspaper about how the Negro Leagues Baseball Grave Marker Project has provided a grave stone for “Creole” Pete Robertson, a New Orleans native who became a fixture on the Black baseball scene in two cities.

Using that article as a jumping-off point, I began work on a blog post that expanded upon the Robertson story, but I eventually got bogged down with the length of the burgeoning post and also became distracted by other projects.

As a result, I decided to publish the post in sections to make it more digestible and less interminably long. Here’s the first such entry; it includes much of the text from the original Weekly article, but also includes some new editions. So, without further ado, let’s get going …

On Feb. 10, 1980, Peter “Creole” Robertson, a former restaurateur who became a major figure in the Harlem community for nearly 20 years, died at Nassau Medical Center in East Meadow, N.Y., on Long Island at the age of 75.

According to an obituary in Newsday, Robertson arrived in New York City in 1938 and five years later opened his wildly popular, 24-7 restaurant at 7th Avenue and 129th Street in Harlem. The noted that the food joint “attracted many celebrities, including Louis Armstrong, Nipsey Russell and Redd Foxx, with its creole [sic] gumbo and other creole [sic] specialties.”

An article in the Baltimore Afro-American added that Robertson also “promoted many dance and sporting events in the city.”

Robertson’s funeral was held at Bethel AME Church on Long Island, but, despite his fame and influence in New York City and Long Island, he was buried in an unmarked grave in Pinelawn Cemetery in Farmingdale, N.Y.

However, tracing back the years, rewinding the tale of Roberston’s life, his story, and his fame, first blossomed in New Orleans. Born in 1905 in Natchez, Miss., Robertson came to the Big Easy at the age of roughly 18 — at the behest of Tom Wilson, a Nashville-based baseball magnate, who pegged Robertson as an ambitious rising talent — and eventually built a small empire as a baseball impresario.

Starting as a slugging catcher for the New Orleans Black Pelicans of the Negro Southern League in the 1920s — he reportedly served as the backstop for none other than Satchel Paige, although there’s no concrete proof that Paige actually played for the Black Pels — Robertson grew in stature and influence in the bustling hive of Black baseball activity in New Orleans.

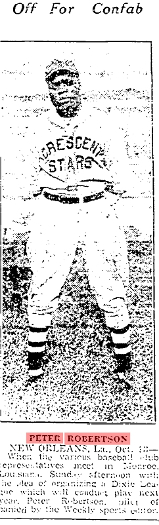

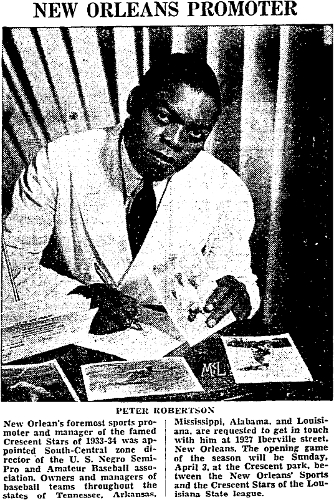

He eventually managed and owned multiple semi-pro and professional teams, including the powerful Crescent Stars in the early 1930s, and became a prime force in the construction of Crescent City Park, which became Black New Orleans’ premier baseball grounds for much of the 1930s and beyond. “Creole Pete” also helped draw top-level Negro League teams from the North and Midwest for exhibitions and other hardball events in New Orleans.

His goal, according to local media, was to replicate the success of the legendary Rube Foster of Chicago, the founder of the first Negro National League and eventual inductee into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, N.Y.

“Peter Robertson lives baseball,” stated the July 15, 1933, issue of The Louisiana Weekly. “Has lived it for years. His chief ambition ever since the day he drew on a catcher’s mitt and decided to play the game was to become a second Rube Foster.”

It’s for those reasons, for his towering influence over 1920s and 1930s Negro League baseball in New Orleans — that his unmarked grave on Long Island, about 1,200 miles from his roots in the Big Easy, is in the process of receiving a stone marker, courtesy of the nationally recognized Negro League Baseball Grave Marker Project.

Created by Jeremy Krock, an anesthesiologist in Peoria, Ill., in 2004, the NLBGMP has raised money and worked to successfully purchase and place headstones or markers at the graves of dozens of Black baseball legends whose careers largely took place during the tragic era of segregation.

Starting with outfielder, Negro League All-Star and championship winner Jimmy Crutchfield, the NLBGMP has brought dignity to the final resting places of team owners, managers and players, including Hall of Famers Pete Hill and Sol White, as well as superstars and Hall of Fame candidates like John Donaldson, Grant “Home Run” Johnson, Bruce Petway, Dan McClellan, Sam Bankhead and “Candy” Jim Taylor. Most recently, the project dedicated a marker in St. Louis for Henry Bridgewater, who founded and created the St. Louis Black Stockings, an important early “colored” ball team in the 19th century.

The Grave Marker Project works with the Society of American Baseball Research to achieve its goal, and author Larry Lester, the co-founder and chairman of SABR’s Negro Leagues Committee, lauded Krock and the NLBGMP for their ongoing efforts.

“The Grave Marker project continues to build momentum and recognition as more unmarked graves are discovered and eventually honored with custom-made headstones, courtesy of Dr. Krock’s commitment in recognizing these forgotten legends of the game,” Lester said.

Lester added that Creole Pete is a perfect candidate for a marker.

“Because of his wide-range of skills, professions and his place in the communities, I think he truly deserves a headstone,” Lester said.

According to Krock, the Robertson effort began when another SABR member, Ralph Carhart of New York City, gave a lecture at the New York State Association of Cemeteries in 2017. Following the lecture, representatives from Pinelawn Cemetery reached out to Carhart about whether any ballplayers might be buried in unmarked graves in the cemetery, and, using the SABR Negro Leagues Committee’s databases, Krock and Carhart discovered Robertson’s grave.

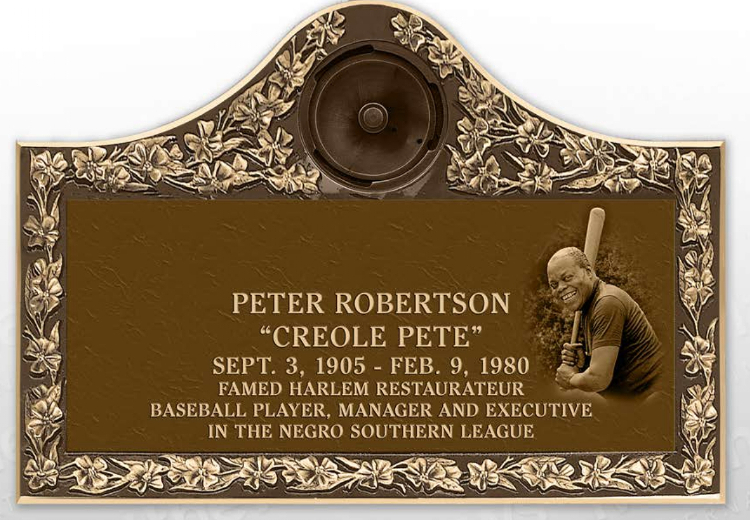

Krock said that Pinelawn continues to work with SABR and the NLBGMP to install a stone at Creole Pete’s burial site. The design of the marker has already been OK’ed, and it features a portrait of an older, smiling Robertson in a batting pose with a bat over his shoulder. The text on the stone reads:

Peter Robertson

“Creole Pete”

Sept. 3, 1905 – Feb. 9, 1980

Famed Harlem Restaurateur

Baseball Player, Manager and Executive

In the Negro Southern League

Krock credited Pinelawn Cemetery with taking the reins of the effort to find funds and move ahead with the stone, which is currently on order.

“The cemetery kind of took it upon themselves to do it and purchase the marker,” he said.

Krock said that SABR and the NLBGMP are working with the cemetery to possibly identify more unmarked graves of baseball figures at Pinelawn.

“[The Robertson effort] was just luck that the owner of the cemetery heard Ralph speak and reached out to us. It’s a wonderful opportunity.

“This is how a lot of our projects go,” he added. “If we hadn’t done this, no one would have.”

And beyond the Robertson project and any other individual NLBGMP efforts, Krock said all baseball figures, and all people, deserve dignity in death.

“As far as we’re concerned,” he said, “there’s no one who’s not worthy of a grave marker. It’s just a matter of identifying the graves and raising the money for a marker.”

Regarding Robertson in particular, Krock added that the process of delving into Robertson’s career made it obvious that Robertson was an ideal candidate for the NLBGMP.

“It was fascinating researching how his career went as a player, manager and owner,” he said. “He did all of those, and we’re proud to be a part of this project. He had a fascinating life.”

Creole Pete most certainly did.

After playing for the Black Pelicans for several years, Robertson tired of the seasonal nature of the baseball business — he reportedly washed dishes during the off-season to earn money at one point — and decided to take up cooking, a skill he inherited from his mother and grandmother. He found a year-round job working in the restaurant of a large New Orleans department store.

He saved money while working at the store and eventually raised enough capital to start his own baseball team, the Crescent Stars, circa 1930. He strengthened the team enough that top-level Black teams teams — like the Chicago American Giants, Homestead Grays, the Kansas City Monarchs and the New York Black Yankees — routinely stopped in the Big Easy for exhibition games with the Crescent Stars.

“I had this team — ‘30 and ‘31 — and at that time none of the major Northern teams came down,” Robertson said. “They didn’t come South because they never could make any money down there. There wasn’t any team good enough, but in two years time I had built up a team down there strong enough to play these teams from the North. And I invited them down with the guarantees that they’ll make money. …

“I was able to take all these teams down there and draw, and make money, because I had built me up the kind of team that could beat these people. And we used to beat them.”

He later bemoaned the fact that these same outside teams routinely poached the Crescent Stars’ best players, which became a factor in him folding up shop in New Orleans and heading North himself.

“After those teams from the North began to come down there and see [the Crescent Stars’ players] they started stealing them,” he said. “They started stealing all of my ballplayers, boys I’ve been training three and four years. The New York Black Yankees brought Zollie Wright and Red Parnell to New York. The Philadelphia Stars took a guy named [Ducky] Davenport. The Chicago American Giants took two or three players.”

“Well,” he added, “you couldn’t blame the boys. They had a chance to go North, get out of the South and get more money than we could pay them. And, after that I didn’t want to go to the trouble of building up another team, because they would just steal them. Then I decided I’m going North [italics in original].”

In addition, Robertson immersed himself in the annual doings of the Negro Southern League, and he periodically attempted to generate enough interest and funding for other regional, state and city-wide leagues.

In the lead-up to the 1932 campaign, for example, Robertson played a key role in a move to create something to be called the Tri-State Baseball League, which would potentially include teams from Louisiana, Arkansas and Mississippi and could, theoretically, challenge the NSL for dominance in the South’s Black baseball scene.

Robertson, as owner at the time of the New Orleans Black Pelicans, traveled up to Monroe, La. – home of the powerful Monroe Monarchs – in late January 1932 for the first official meeting for the fledgling league. While a dozen or so cities reportedly expressed interest in joining the circuit, the Louisiana Weekly stated that a “Big Four” franchises would lead the way – the Black Pelicans, the Monarchs and clubs in Little Rock, Ark., and Jackson, Miss.

However, by late February, the prospects of a successful launch of the lead dimmed, apparently despite all the enthusiasm from Pete, who, according to the Weekly, “has made plans to rebuild the Black Pelican Club and thrust it into the [league] hook-up, is rather dubious about some things these days.” The paper reported that Robertson hadn’t heard from the league headquarters in Monroe for weeks.

But regardless of whether or not the league would take off – it wouldn’t – Robertson was reportedly determined to give the Crescent City the best possible team.

“But reply or no reply [from Monroe],” reported the Weekly’s Earl Wright, “league or no confederacy the big former Black Pelican catcher says he is going to put a baseball team on the diamond.”

Within a couple weeks, the chances of a Tri-State Baseball League disintegrated when the Monroe Monarchs, who by then were arguable the best Negro Leagues team south of the Mason-Dixon Line, bailed on Robertson and the other team hopefuls to become the anchor of a revived NSL.

(The decision by the Monarchs to jump circuits was probably a smart one, and certainly understandable, especially because with the demise of the first Negro National League in 1931, the NSL was improbably emerging as the nation’s one and only Negro major league in 1932. Monroe emerged as the best team in the 1932 NSL and lost out on claiming the league title thanks to a questionable turn of events and bureaucratic smoke and mirrors that gave the crown to Cole’s American Giants. For more detail on the entirety of the 1932 Blackball season in the South, definitely check out Tom Aiello’s fantastic book, “The Kings of Casino Park: Black Baseball in the Lost Season of 1932,” an excellent history of the Monroe Monarchs.)

Thus began the baseball seasons of 1932 and ’33, which ended up representing both Robertson’s pinnacle as a baseball magnate, and a crucial turning point in his career, his life and the sport he loved in New Orleans.

More Creole Pete stuff to come …