Editor’s note: Here’s another slice of prime Creole Pete Robertson, following the first entry here. For this one, we jump ahead some to Pete’s arrival in New York City following his move in the 1930s from the Big Easy to the Big Apple, where he eventually established himself as a vital and vibrant part of the African-American community by bringing his passion for N’Awlins food to the denizens of NYC.

This is taken from my lengthy essay about Pete that I started more than a couple years ago. I apologize for kind of jumping around within the narrative and shifting between time periods from one post to the next. Because this project has dragged out a good deal, I want to publish what I can now.

But first, a few paragraphs about Robertson’s extremely tight friendship with another New Orleans native son who eventually also settled in New York City and made a global name for himself: None other than Satchmo himself.

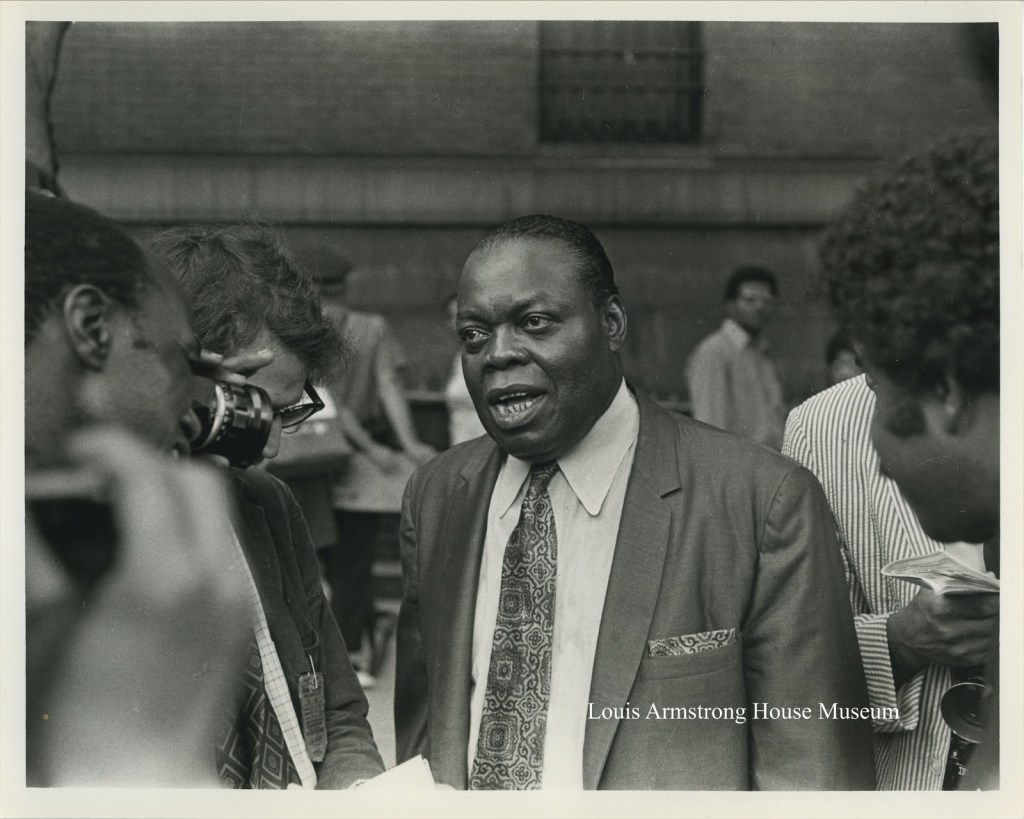

One final, New Orleans-themed note about Creole Pete: Robertson was extremely close with the Big Easy’s favorite son, none other than Louis Armstrong. By many accounts, Satchmo and Robertson were as tight as siblings; in fact, Pete frequently called Louis his “brother.” The Louis Armstrong House in Queens includes about a dozen archived materials involving Robertson, including pictures, a telegram, articles and a Christmas card.

When Armstrong died in July 1971, the Amsterdam News asked Robertson for his reaction.

“He was just like my brother,” Pete said. “I lost a part of me when Louis Armstrong died.”

The Amsterdam News’ Les Matthews described the scene at Satchmo’s funeral in Flushing Cemetery after the service.

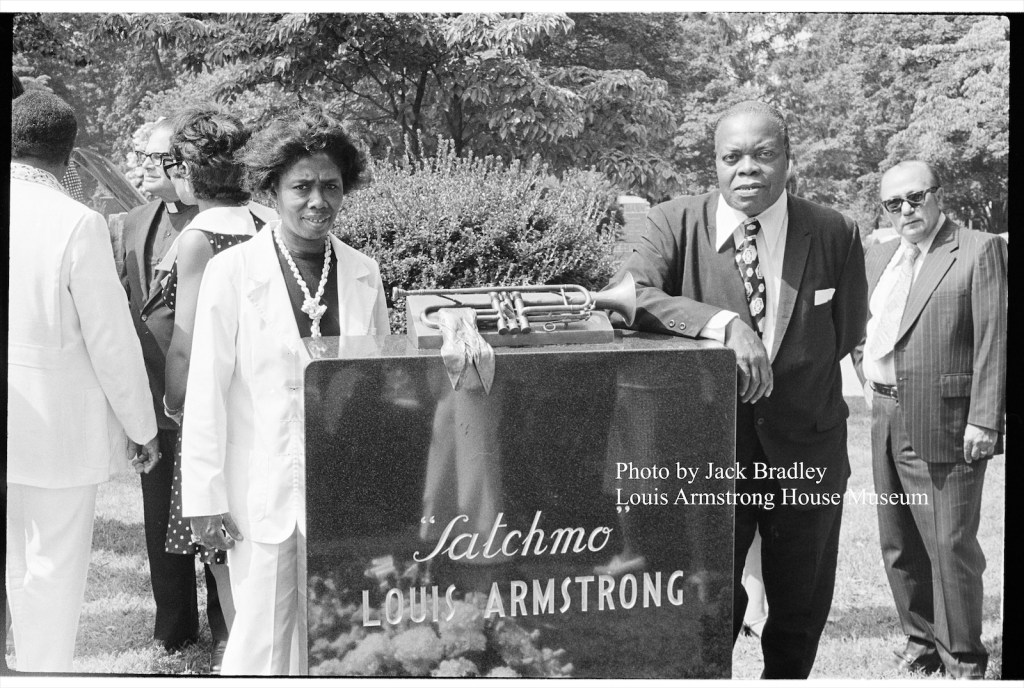

“‘Creole Pete’ Robertson, a lifelong friend whom many thought was Armstrong’s brother did not want to leave the Flushing [C]emetery,” Matthews wrote. “There was a strong bond between the two men.”

A quirky anecdote illustrating the NOLA-born connection between Pete and Satchmo, courtesy of a 1955 Jet column about one of Louis’ concerts:

“At his opening at Broadway’s Basin Street, Louis Armstrong spied two long tables of his native New Orleans cronies, hosted by Al Cobette and Pete Robertson, [and] quipped, ‘There’s a lot of gumbo eaters here tonight.'”

I’ve been in touch with Ricky Riccardi, director of research collections at the Louis Armstrong House and Museum, to get perhaps a deeper appreciation for Creole Pete’s relationship with Satchmo. Riccardi is one the preeminent modern scholars, researchers and writers regarding Armstrong; his incredibly comprehensive new biography of Louis, having published two biographies of Armstrong, including 2020’s “Heart Full of Rhythm: The Big Band Years of Louis Armstrong.” Riccardi also earned a Grammy for his liner notes for the Mosaic label album, “Complete Louis Armstrong Columbia and RCA Victor Studio Sessions 1946-1966.”

Ricky graciously wrote up a short essay about the relationship between Robertson and Armstrong for this blog; here’s a few excerpts from the article by Ricky, to whom I extend my heartfelt thanks for all his assistance and input about Creole Pete:

Born in Mississippi in 1905, Robertson spent part of his youth in New Orleans, where it’s possible he first met Armstrong; they certainly looked alike to enough to sometimes be mistaken for brothers!

Robertson spent time in the Negro Leagues, where he was catcher to the legendary pitcher Satchel Paige, but he made his most lasting impact on the citizens of Harlem with the opening of Creole Pete’s at 2700 7th Avenue in 1938. Armstrong almost immediately became a regular; Creole Pete’s remained his venue of choice in New York City when he craved a taste of home.

More importantly, Creole Pete himself became a friend. Digging through the Louis Armstrong Archives, one finds photos of Creole Pete backstage with Louis throughout the 1950s and 1960s, at venues such as Freedomland in the Bronx; one photo of Robertson even turned up in one of Armstrong’s collages; There are telegrams and Christmas cards from Creole Pete and his family. Even after Louis’s passing, Creole Pete remained in his orbit, invited to Louis’s widow Lucille to the dedication of Louis’s headstone in 1973 and to participate in a New Orleans Jazz and Food Festival at the Rainbow Room that same year.

Though he remained — and remains — far from a household name, these archival treasures illustrate a close bond between Armstrong and Robertson that lasted several decades, a testament to their friendship and the power of good home cooking that often brought them together.

— Ricky Riccardi

For more of Riccardi’s article to me, see the quotes section below, because he relates quite a tale about Louis and Pete. Again, many thanks to Ricky and the Armstrong House for the contributions, including the incredible photos!

The bond remained strong throughout Pete’s and Satchmo’s lives, both in their hometown town down South and when they each relocated to the Big Apple. For a little info on Louis’ life in NOLA, check out this piece, but when it came to the second chapter of Robertson’s life — that of his time in New York — we start in the late 1930s, when he moved to New York.

(According to George Palmer of the Amsterdam News, Robertson moved to New York City on the oddly specific date of Aug. 2, 1938 and opened the restaurant in 1943.)

While living in the Empire State, Robertson’s life continued to be a hurlyburly of money, influence and even a little intrigue. Before he opened his famous restaurant, Robertson operated an illicit “after hours” club in Harlem, but he decided to get out of that fast lane because New York cops began squeezing him for bribes.

But once he got his cafe up and running, he and his Creole joint quickly became staples of Harlem society and nightlife. For almost two decades, Pete boasted a lavish down-home Louisiana menu and a massive, star-studded clientele. (According to an Aug. 6, 1975, article by George Palmer in the Amsterdam News, Robertson’s famous nickname, “Creole,” was coined by actor and entertainer Nipsey Russell, who frequented Pete’s gumbo joint.)

“I looked all over Harlem trying to find a good spot and a safe spot,” Robertson said in a 1974 interview with Black Sports Magazine. “Finally I found a location on Seventh Avenue and that’s when I opened up Pete’s Creole Restaurant. Boy! That was home for all the celebrities — Sugar Ray Robinson, Joe Louis, Phil Rizzuto of the New York Yankees, Bob Feller, Satchel Paige, they all used to be there.

“I was open 24 hours and business was terrific every night,” he added. “I did my best business between 2 a.m. and 9 a.m. Everybody in show business used to come to Creole Pete’s Restaurant when they got off work. A lot of people used to come just to see the celebrities.”

He then added: “Well, when I first came to New York, they didn’t have a real first-class restaurant in Harlem. Being from the South, I believed in eating, and eating good. Most New Yorkers were from the South and they loved that soul food. But my number one special was Creole food, because I was from New Orleans.”

The menu included (in Pete’s own words), “Louisiana Creole gumbo, Creole shrimps [sic], Creole Chicken, Creole pork chops, hot sausage Creole style … and Louisiana Creole gumbo.” He called Creole dishes “the greatest of foods,” and, he added not so modestly, “I consider myself the No. 1 person in making it.”

Pete even bragged that his gumbo would fix up a hangover better than Pepto Bismol.

“If you’re a person that drinks and you have a tendency to get a little sick from drinking, you can always eat that Louisiana Creole gumbo and it’ll always straighten you out,” he said. “It has so many different vitamins in it and so many different sauces, herbs and spices that it’ll sober you right up.”

Pete’s cuisine digs gained some mention in Jet magazine in 1952, when the publication, under its “New York Beat” section, noted that Robertson “spent more than $20,000 in redecorating his House of Gumbo Cafe, then sent to his native New Orleans and imported a chef and ten creole [sic] beauties as waitresses. Five of them made over $150 in tips alone the first week.”

One of the earliest, and most effusively comprehensive, articles about Pete’s still-new restaurant was the December 1994 “Harlem Night Life” column by Wally Warner in the New York Age.

In the column, Warner cites Curley Carter, a chef imported from New Orleans who was responsible for creating and cooking up the joint’s already-famous gumbo.

“If you took his kitchen away from [him],” Warner wrote of Carter, “he’d probably want to die. Curley has been cooking for over thirty years. His English isn’t very articulate to describe his artistry of food. He welcomes you into the kitchen to sample his sauces and other dishes. They taste very good, so you ask him the secret to his culinary genius, but with so many continental terms to unmask – he just smiles and say [sic], ‘That’s the way I always do it. His own favorite dish is craw fish [sic] bisque, creole [sic] style, with candied yams, string beans and sauce.”

According to Warner, another Pete’s staple was seafood, and lots of it, including “[o]ysters, clams on half shell, deviled crabs, shrimps [sic], Spanish mackerel, weakfish, sea bass [and] filet of sole.”

The bottom line, Warner wrote, was that Creole Pete’s digs were all about no-frills, unpretentious, downhome charm.

“The price is fitted to your purse,” the columnist enthused. “Don’t go to Pete’s looking for glittering trimmings; the restaurant is undecorated except for a few still lifes of celebrities on the wall. The atmosphere is restful and the service is deft; this reflects the reason why Pete’s is one of the busiest restaurants in Harlem, satisfying the discriminating appetites of celebrities, professional people and the average John Q. Public …”

In 1954, Daily News lifestyle columnist Robert Sylvester reported on Robertson’s business, with special emphasis on Pete’s Creole stew concoction.

“You get a big dish of gumbo for exactly $1 and you can also get wonderful barbecue ribs,” Sylvester wrote. “… I promise you it’s a big bit for a single buck.”

The coverage in the Daily News was significant — it showed just how popular Pete’s joint had become that word of the restaurant had crossed over into the mainstream press. In fact, Sylvester and the Daily News again hyped up Robertson and his Creole chow in 1958, when the scribe reported on a party given by famed jazz trombonist Tyree Glenn at Glenn’s home in New Jersey for radio personality Jack Sterling. The wang dang doodle was catered by none other than Robertson, and Sylvester lauded Pete for the latter’s two career aptitudes.

“The other night [Glenn] gave a party for Jack, and since he wanted to do something special for Jack and his CBS crew, Ty dug up Creole Pete Robertson,” Sylvester penned. “Pete has two distinctions. He was Satchel Paige’s first catcher and he can make a New Orleans gumbo which is enough to make you wake up in the night screaming for more.

“If you’ve never eaten gumbo,” Sylvester added, “you haven’t really lived. It’s got rice and ham and chicken and a hundred strange spices and a broth, and right in the middle of every portion is a small cooked crab. Man, it is pure heaven.”

In February 1947, the restaurant even garnered a few words on the Daily News sports page, where legendary sports editor scribe Jimmy Powers — who was a steady, vocal proponent of integration in baseball for much of his storied career — sang the joint’s praises.

“Peter Robertson, retired ball player, now has one of Harlem’s best eating establishments, specializing in Louisiana gumbo,” Powers wrote.

(Pete also brought the same savvy he employed as a baseball magnate to his restaurant business, and he wasn’t above trying to butter up the local media for some free advertising, so to speak. In May 1952, he hosted local journalists for a lavish Creole feast, prompting the New York Age’s Edward Murrain to claim that the members of the press were “still panting from the effects of the wonderful food ‘Creole’ Pete Robertson put on for the fourth estate at the opening of his renovated restaurant …”)

Robertson wasn’t just a Creole culinary master and businessman supreme while he was in NYC. During his time as a bigwig in Harlem life, Robertson took on a slew of challenges, including briefly running for the informal title of “Mayor of Harlem” in 1948. (More on this below.)

Another sign of the esteem in which Robertson was help among the folks of Harlem and New York City came in May 1964, while the New York City Council was discussing creating an all-civilian review board to conduct investigations into citizen’s complaints of police abuse, brutality and other instances of NYPD misconduct. The Amsterdam News’ James Booker and Les Matthews conducted “man-and-woman-on-the-street” interviews with local politicians and civic leaders, including Robertson.

“The creation of a civilian complaint board is a good thing,” Pete told the journalists. “An outsider can usually see better than someone that’s inside. The body must have the right people, however.”

In addition to his reputation as a restaurateur civic leader, Pete cut a dashing figure in Harlem thanks to his knack for fashion. Wally Warner of the New York Age noted that Robertson stood at five-foot-11 and tipped the scales at 185 pounds, with brown eyes and “large, muscular hands. … His taste in dress is both fussy and flamboyant, running from light gray suits and carefully matched sport ensembles; he favors double-breasted suits.”

Robertson also welcomed to his restaurant a galaxy of national stars and new and old friends from the worlds of music, sports and politics; chaired the Harlem Citizens’ Committee; founded the Harlem chapter of the Louisiana State Club; and provided catering services for charity events, such as the Amsterdam News Welfare Fund Midnight Show at the Apollo Theater.

(The 200-member Louisiana State Club, mentioned above, apparently was quite active in Harlem, working to bring a further taste of the Big Easy to those in the Big Apple. In 1953, for example, the club celebrated that most New Orleans of events, Mardi Gras, with a three-day ball that cost more than $6,700. Robertson, naturally, served as “King of the affair,” noted Jet magazine.)

In 1960, he founded and served as president of Creole Pete’s L&M Social Pleasure Club, reported the Amsterdam News, which stated that the “purposes [of the club] are precisely what the name implies. … It plans to promote good fellowship of New Yorkers who are natives of Louisiana and Mississippi, their families and friends. … The club does plan to aid civic and educational activities.”

Creole Pete also liked boxing. Or rather, he liked watching and promoting it, a passion that led him to try to bring prime-time fights to Harlem’s Rockland Palace in the late 1940s. In November 1948, the New York Age reported that Robertson, “well known sportsman,” expected to open the venue to fights in January.

The Palace, it said, was the “scene of many historic ring battles,” including fisticuffs involving, among other pugilists, Jersey Joe Walcott, Elmer Ray, George Brothers, Panama Al Brown, Cocoa Kid (Herbert Lewis Hardwick), Kid Chocolate and Lorenzo Pack. According to the Age, Robertson had already booked Sugar Ray Robinson to open the boxing series. It’s unclear, however, if Robertson was successful in actually bringing matches to the Rockland Palace.

(The Rockland Palace is its own unique story. Founded by the Odd Fellows, over its decades and decades of existence, the venue welcomed an array of events, including concerts, political rallies, church sermons, sporting events and banquets. It housed the home court of the Harlem Yankees pro basketball team, and it was often a locus of LGBTQ social activities, including lavish drag balls.)

Even in the last phase of his life, Robertson helped lay the groundwork for something special in a third community. After selling his Harlem restaurant in 1955, Creole Pete eventually moved to the Nassau County community of Roosevelt on Long Island, and by the early 1970s he became a significant figure in his new home.

(An interesting note: according to issues of Jet in in the late 1950s/early 1960s, Pete had by then become a head chef-cook at a restaurant/cafe owned by ex-heavyweight boxing champ Jack Dempsey.)

Informal and unspoken patterns of segregation — such as housing red-lining, white flight and disproportionate government spending — led to Roosevelt developing into a majority African-American community where many middle-class Black New York City residents, such as the Robertsons, moved to after leaving the big city for the quieter confines of the suburbs. Despite a long history riddled with challenges to its educational system and a lack of representation in county government, Roosevelt blossomed into one of the Northeast’s most economically better off and culturally rich Black communities.

But Robertson’s family was also not immune to tragedy. Pete’s eldest son, Pete Jr., was murdered in 1979. Another son, Pablo, starred in basketball, eventually playing with the Harlem Globetrotters and blossoming into one of the flashy early stars of the famed Rucker Park community basketball courts. However, just 10 years after his father passed away and 11 years after his brother, Pablo died at the age of 46.

But even with the parade of stars as friends, the accolades for his tasty gumbo at his bustling restaurant, and his social and political influence, Robertson never lost the love of the national pastime that he nurtured in New Orleans.

He served on committees that planned and raised money for Jackie Robinson Day and Roy Campanella Day, which honored two of the earliest integraters of baseball and Brooklyn Dodgers stars, as well as a similar celebration for the New York Giants’ Monte Irvin.

In 1948, the Amsterdam News reported that Robertson was “rated the best baseball authority in Harlem,” and in 1950 the New York Age stated that Robertson was ecstatic “over his two kids who are big enough to dig baseball.”

Robertson’s vast knowledge of and passion for baseball led to him being one of several Harlemites interviewed by the Amsterdam News in 1949 about how Negro League Baseball could survive after all the Black game’s best players had been plucked by the Majors.

In his comments, Robertson said schools and other community institutions should start growing their amateur baseball programs, and he proffered that existing Negro League teams should enter “Organized Ball” as whole entities, which he theorized would help white America learn about Black baseball.

Ultimately, he said, the Negro Leagues still retained the potential to thrive.

“With proper handling, the [Negro] league could definitely be improved,” he said. “There is more interest in the game today than there was formerly and this is one of the main factors which would help the sport, which should have a place in the national sport picture. The Negro leagues [sic] cradled the boys who are in there now and gave them the chance to be seen.”

While he kept one eye on the Negro Leagues, Robertson also paid keen attention to what was happening in the Majors, which, by the 1950s, had drawn many African-Americans’ attention away from Black ball.

In June 1951, Jack Dalton of the New York Age talked to Robertson — who had always maintained his renown as a baseball fanatic — about the fever pitch of baseball competition in New York.

“Peter Robertson, who knows more about baseball than ninety-nine percent of the New Yorkers, claims that the Giants will have all the Yanks [sic] business within the next year,” Dalton wrote.

Such a prediction would have been a popular one in the Big Apple, especially among the city’s Black baseball fans, many of whom keenly cheered for the Giants, whose lineup featured several African-American players, including Willie Mays, Monte Irvin and Hank Thompson, while the Yankees wouldn’t integrate for another five years.

(Robertson and other Black baseball fans were keen supporters of Irvin, who crossed over from the Negro Leagues to the majors during a Hall of Fame career; in August 1951, Pete was part of a group working toward having a Monte Irvin Day at the Polo Grounds.)

But for now, the tale of Pete Robertson, both in life and now in death, is a huge success story. Although he left the Crescent City in the 1930s and became a big wheel in Harlem and on Long Island, Robertson remained a New Orleanian and a Louisiana man through and through — as a baseball player, owner and lifelong fan, and as a man with culinary expertise and an eccentric, extroverted personality.

In the aforementioned 1974 article in Black Sports Magazine, Creole Pete extolled the virtues and excitement of the city where he forged his career and began his incredible life.

“… Creole food is a certain type of food that [Creoles] create. I’m not a Creole, but I know how famous the food is. Everybody who’s been to New Orleans and had Creole food always wants to get it again. And I could really fix it.”

But when it comes to creating something New Orleanians love, Robertson was, for 20 years, a master of the Crescent City baseball scene. He loved food, and he loved baseball, and he always approached the latter, just like Creole cooking, with zeal.

His beloved Big Easy never forgot him, either. In June 1958, while Robertson was enjoying three weeks of vacation in New Orleans, plans were laid out for a “Night in Honor of Creole Pete,” reported Elgin Hychew of the Louisiana Weekly newspaper. The publication added that Pete [had] been away from New Orleans 25 years and is famous for his New York eating place which is known the world over.” The gala was held at the famed Dew Drop Inn and hosted by club owner Frank Painia, and according to an ensuing article headline in the Weekly, it was a “howling success.” (More on the celebration below.)

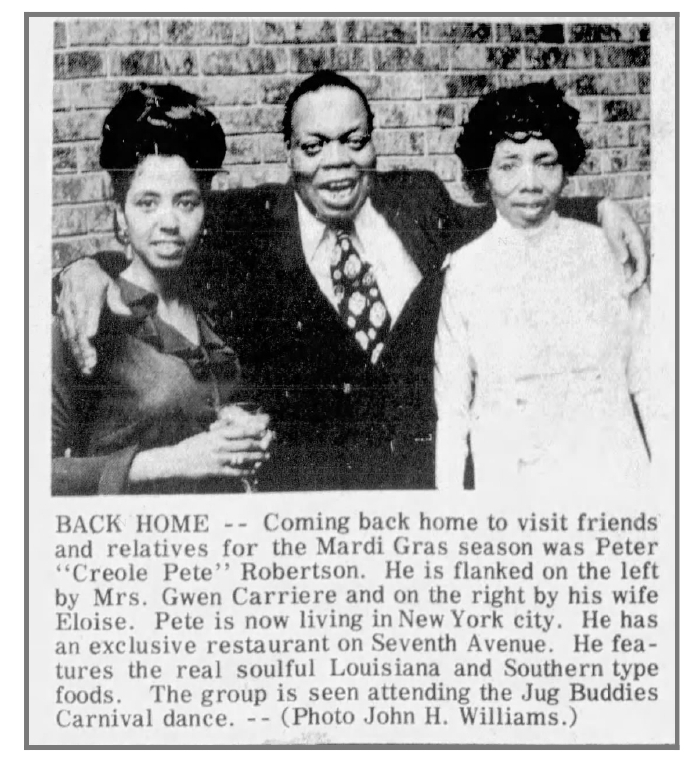

Robertson, with his wife Eloise, made another return to New Orleans for in March 1973 for Mardi Gras as well, when he was similarly feted and received very warmly by his lifelong friends and loved ones in the Crescent City.

In particular, he gathered with a bunch of his old Big Easy baseball chums at Mule’s Restaurant and Bar, which stills stands today on Laharpe Street in New Orleans. It apparently was an evening of boisterous reminiscing about the golden days of N’Awlins Black baseball 40 or so years earlier. Joining Pete were Percy Wilson, Robert “Black Diamond” Pipkins, Herman Roth, Milfred Laurent and Edward “Squatter” Benjamin.

Finally, for now, a bunch of quotes from and about Pete Robertson that I wanted to show readers without further elongating the main text of this already too long screed; I figured that if I included the quotes as a little addendum, it wouldn’t bog down the main body of the post. So, here we go!

First, we have thoughts on Pete’s Creole Restaurant, from Pete and from fans …

From an article by Major Robinson in the Amsterdam News from April 11, 1987:

“Or what about Creole ‘Pete’ Robertson, a former Negro League baseball player from New Orleans, whose specialty was hot and spicy dishes such as dirty rice and gumbo. Often after a game at the Polo Grounds or Yankee Stadium one could find celebrated pitcher Satchell [sic] Paige polishing off a plate of Jambalaya (Cajun rice, shrimps [sic], chicken, beef sausage with a plate of red beans and rice on the side).”

From New York Age night life columnist Wally Warner in March 1946:

“Peter Robertson, owner of Pete’s Restaurant … has developed a smart continental-style restaurant by using the personal touch. He thinks in terms of friends instead of customers. This has resulted in busy days for all concerned — starting with breakfast and continuing on through dinner and late supper.

“No one calls Pete Mr. Robertson more than once; he makes everyone too much at home for formalities. A connoisseur of years standing, Pete likes to supervise each order with a waiters [sic] concern for service. For dinner for instance, he’ll take a menu and sidle over to [a] table and ramble off suggestions, telling at the same time how he prepares his dishes. And when he’s through you may find yourself deviating far from the routine of your regular diet …”

From Pete himself, in Black Sports Magazine, December 1974:

“Louisiana Creole gumbo carries practically every vitamin in the book. Most dishes carry one vegetable; Louisiana Creole carries five vegetables: onions, peppers, celery, okra and tomatoes. Now the meats. The meats that go into it are smoked sausage, smoked ham hocks, chicken, turkey, veal. The brain food in a gumbo is shrimps and crabs. It is served with rice. It’s not a stew and it’s not a soup; it’s between the two. That’s the original Louisiana Creole Gumbo.”

In an article by Robert Sylvester of the New York Daily News in September 1954:

“Pete Robertson operates his gumbo palace 24 hours a day at Seventh Ave. and 132d St. You get a big dish of gumbo for exactly $1 and you can also get wonderful barbecued ribs. Gumbo is served in a bowl. It has rice and okra and chicken and ham and other stuff. It also has special herbs which Pete brings in from New Orleans. In the middle, floating in the stew, is a small crab boiled in its shell. I promise you it’s a big bit for a single buck.”

We now go to Pete Robertson, baseball philosopher and kingpin, with a few quirky and colorful comments from the man himself. Throughout his life, no matter what other challenges he tackled and ventures he launched (entrepreneurial, charitable or otherwise), Creole Pete remained intimately connected to the sport he played, managed and loved. He never ventured too far away from his first love. To wit …

In July 1953, the Associated Negro Press’ Al Moses somewhat randomly quoted Robertson musing on players’ natural mitts:

“Most of the important ball stars had what I call pocket hands,” Moses quoted Pete as asserting. “The horsehide seemed to fit perfectly in their giant paws, seldom falling out.”

Robertson also pontificated about what the future held for Negro baseball for an article in the Amsterdam News in August 1949:

“With proper handling, the [Negro] league could definitely be improved,” he said. “There is more interest in the game today than there was formerly and this is one of the main factors which would help the sport, which should have a place in the national sport picture. The Negro leagues [sic] cradled the boys who are in there now and gave them the chance to be seen. Now schools and other institutions have added this game to their programs and more and more are playing it as a direct result. I think the best way to revive the game would be for the Negro teams to enter organized ball as classified ball teams. The public is not too well informed about the Negro teams of today and by entering organized ball they would have a better chance to be seen and heard from.”

Pete was also frequently asked about his opinions on hot news topics of the day.

By Amsterdam News reporter Milton Mallory, who in November 1953 collected sidewalk interviews that included Robertson, about the possibility of a lottery in New York:

“Yes. I think [the] lottery should be legalized, it would take some of the heavy taxes off the business man. The City and State would receive enough money to build better schools and highways and maybe come out with a little reserve for miscellaneous.”

An article by the Amsterdam News’ James Booker and Les Matthews, about the idea of a civilian review board for the NYPD, in May 1964:

“The creation of a civilian complaints board is a good thing. An outsider can usually see better than someone that’s inside. The body must have the right people, however.”

Then, the Amsterdam News in May 1967 quoted Pete regarding Muhammad Ali’s stand against the Vietnam War draft:

“Well, he said he is a minister and he should be exempt. I believe that Muhammad Ali’s outspoken attitude played a big part in the decision of the judges. I don’t think they should take his title away either.”

As mentioned previously in this post, Pete was so popular in his NYC surroundings that he briefly ran for the title of “Mayor of Harlem” in early 1948. Although the position was largely ceremonial, and although he withdrew from the campaign after a few months, the fact that Robertson was drafted into the race reflects his massive popularity among his fellow Harlemites.

While he was still in the race, in February ’48 Creole Pete outlined his “platform” for the “mayoral election,” as detailed in the Feb. 7, 1948, edition of the Amsterdam News. Here’s a few thoughts from him about what he’d be able to bring to his “constituents” if he was elected …

“My general and overall plan for the improvement of Harlem is very simple and easy to understand. It is my belief that the surest means of eliminating practically every civic evil in Harlem is through the constructive guidance of our young people in the elevation of recreational and sanitational standards through our own efforts.

“It has long been agreed by everyone that something should be done along these lines but as yet no one has ever outlined exactly WHAT [caps in original] should be done. I have what I believe to be a workable plan that will demand something of all yet not be unduly expensive to any one person or group of persons. …

“I do not choose to make any empty campaign promises. I will simply state that if the people of Harlem select me as their ‘Unofficial Mayor’ I shall sincerely lend my every talent and resource to the performance of that office.”

Here are thoughts by the unnamed writer of the article:

“As a candidate in the “Harlem Mayorality” race, Peter Robertson is perhaps the best known and most colorful figure of all. The popular restaurateur, more popularly known as ‘Creole Pete,” has long been prominent and active in Harlem’s civic programs. By possessing all of the attributes which go to make a good citizen with keen public consciousness, Pete’s qualifications for the position of Harlem’s “Unofficial Mayor” are many and worth the listing.

“’Pete’ has done many things to promote the general welfare and to develop a better way of life in Harlem, and not the least of these have been his many substantial donations to many of the community charitable enterprises. He was one of the very first to come through most liberally with donations for the Harlem Serviceman’s Center, the Sam Langford Fund, the Amsterdam News Welfare Fund, the New York Baptist Fund and the Sydenham Hospital Fund to mention a few.

“It has always been with great pride that ‘Pete’ has noted the achievement of any Harlemite or member of the Negro race. During the recent Jackie Robinson ‘Day’ campaign, ‘Pete’ served as a committeeman, working diligently and devoting much time and effort. Because of his labors he was responsible in raising one of the largest amounts of money accounted for in the entire drive.

“Being a family man, and the father of two fine, robust boys, ‘Pete’ has a heartfelt concern for the less fortunate children of Harlem. Because of this concern he has always been a heavy contributor to the Mother Goose Kindergarten Nursery and the Riverdale Orphanage.

“A tall, always smiling man of boundless energy, ‘Pete’ has innumerable social interests. He is very active in the Young Men’s Christian Association program and is a member of the Metropolitan Stevedore Club, the Independent Political Association and the Louisiana State Club. He was founder and organizer of the latter.

“Known and admired by all of Harlem’s hundreds of stage, screen and radio folk, ‘Pete’ has been assured by them of their support to his campaign and, if he is elected, he has their promise of cooperation with the administration.”

Finally, we’ll finish out with a bang, with another excerpt from Ricky Riccardi’s article to me. Enjoy, and thanks as usual to all who are reading:

“In September 1952, Louis Armstrong sat down for a radio interview backstage at the Paramount Theater with broadcaster Sidney Gross. As Gross began taping the conversation, Armstrong taped it, too, adding to his private collection of hundreds of reel-to-reel tapes. Early in the interview, Gross noticed Armstrong eating a bowl of gumbo and asked him how it made him feel. “Well, I feel like I’m right in the heart of New Orleans right now.’

“Wasn’t that wonderful? Gross asked, before addressing his audience. “Incidentally, everybody down at WSMB, tonight I was introduced by Creole Pete, who’s one of the great cooks in New York, brought along a steaming bowl of Louisiana Creole gumbo.’

“How’d you like it?’ Louis asked.

“Oh, it was really wonderful,’ Gross replied.

“You made yourself proud, you know that? You stepped up there!’ Armstrong said, before noting that joining them for the feast was vocalist Velma Middleton, Louis’ valet Hazes “Doc’ Pugh, and Creole Pete Robertson himself. Louis decided to give his friend one more plug of the air.

“You want to take the family to Pete’s restaurant sometime,’ Armstrong implored. “It’s up there on 131st and 7th Avenue in Harlem so you can really rest and relax and spread out on that table and really have a ball at Pete’s.’

“I must do that,’ Gross promised, caused Armstrong to insist, “You must visit him, anyway.’ That particular feast was paid for by the famed arranger Gordon Jenkins, who was sharing the bill with Armstrong at the Paramount. “Music maestro Gordon Jenkins’ gumbo food bill, when he played the Paramount Theater with Louis Armstrong, was $300. He had Creole Pete Robinson [sic] bring him the New Orleans dish every night backstage,’ Jet magazine reported on September 27, 1952.”