As my blogging production slows to a trickle — and, perhaps, to a temporary halt at some point — I did want to revisit one of my posts from, geez, August 2020 about the bunch of New Orleans Negro Leaguers who ended up in the Great White North — Broadview, Saskatchewan, to be specific — in the 1930s.

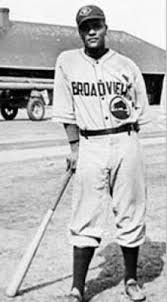

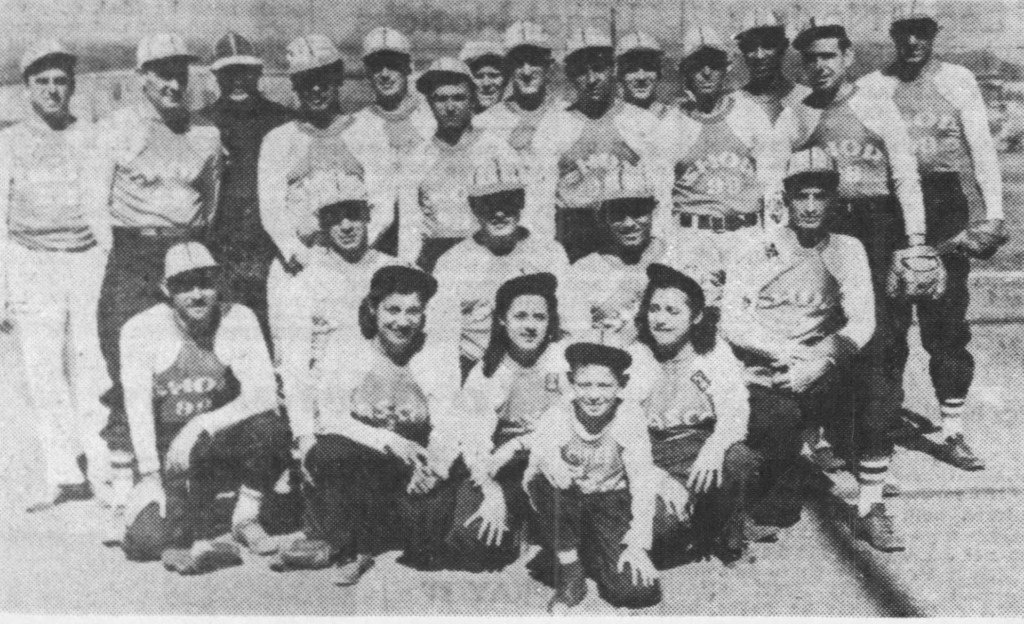

This group of Pelican State ringers helped make the Broadview Buffaloes of the Southern League in Saskatchewan an absolute juggernaut for three seasons, from 1936-1938, racking up pennants and attracting fans in droves during the brief but balmy summers on the Canadian prairies.

The Louisiana-infused Buffaloes of those glory years were deservedly inducted into the Saskatchewan Baseball Hall of Fame in 2017. Check out my original post here, as well as this great Web site for the Sask Hall of Fame, and this comprehensive, colorful site about the history of Western Canadian baseball.

Those Pelican Staters in Saskatchewan included Eugene Bremer, a New Orleans lad who pitched for several Big Easy teams in the 1930s before eventually cracking into the Negro League majors with the Memphis Red Sox, Kansas City Monarchs and Cleveland Buckeyes; Lionel Decuir, a catcher and centerfielder from N’awlins who later played briefly with the Cincinnati Tigers, Pittsburgh Crawfords and Kansas City Monarchs; pitchers Red Boguille and George Alexander, whose careers mainly took place in Louisiana; and the gentleman who’s the subject of this post, Freddie Ramie.

On kind of a side note, it’s important to mention the role the Canadian minor leagues of decades past played in the overall racial integration of baseball. For example, the first wave of Negro Leagues players signed by the Brooklyn Dodgers beginning in late 1945 — a decorated group of trailblazers like Jackie Robinson, Roy Campanella, Don Newcombe, Johnny Wright, Roy Partlow, Junior Gilliam and Joe Black — cut their teeth in Organized Baseball in Canada with (depending on the individual) the Montreal Royals of the International League, the Trois Rivieres Royals of the Can-Am and Provincial leagues and the Granby Red Sox of the Provincial League.

But other Black ballplayers engaged in the annual seasonal migration from the States up North across the border, where legalized segregation didn’t exist (or at least on a much smaller scale as in the U.S.) and players (and, at times, managers) of color were treated with a lot more respect than they could ever find in the United States, especially in the South, where the aforementioned group of Louisiana fellows toiled for much of their careers.

The prevalence of Negro Leagues players heading north is chronicled in several resources, including the book, “Black Baseball Players in Canada: A Biographical Dictionary 1881-1960,” by Barry Swanton and Jay Dell-Mah.

“Going over [some] records …, I realized that all these great players from the Negro Leagues played here, as well as a few major-leaguers and some pretty good local players,” Swanton told the Winnipeg Tribune in 1996. “Satchel Paige pitched for Minot Mallards of the ManDak League in their first three games against Brandon, Carman and a team in Minnesota, and he didn’t give up any runs, striking out 11 or 12 players.”

And segueing from that, one perfect example of this desire to play in the Great White North, especially in Western Canada, was the relative flood of former Negro Leagues who enjoyed the twilight years of their careers playing in the ManDak League, an independent minor league encompassing teams in – you guessed it – Manitoba and North Dakota. Many a former Negro Leauguer spent a season or more plying their trade in the ManDak, a phenomenon that’s chronicled quite well in the book, “The ManDak League: Haven for Former Negro League Ballplayers, 1950-1957,” by Swanton.

So, as such, the experiences of the Louisiana lads in Saskatchewan were not completely out of the ordinary.

(To that point, it should be noted that the Pelican Staters weren’t the only Black ringers the Buffs imported from the States; several other standouts were lured north of the border to help Broadview steamroll the competition. In many games, African Americans outnumbered native Canadians in the team’s game lineups, with Black players making up two-thirds of the Broadview scorecard or more. Such a situation further underscores how Canadian baseballers held more progressive views on race than us here in the U.S., and how canucks were willing and even eager to plumb the ranks of the Negro minor leagues in their quests for championships.)

But back specifically to the Pelican State chaps in Saskatchewan in particular. Bremer was one of the first Louisianians to sign up for action in Saskatchewan, and he was subsequently joined or followed by Decuir, Alexander, and Red Boguille.

The aforementioned players suited up in various combinations in various years for Broadview between 1936-38, the years for which the Buffaloes were inducted into the Saskatchewan Baseball Hall of Fame. Some of them did don the spikes for Broadview in the years before that sterling three-year period, and one or two after that stretch as well, and we’ll get into the post-1938 years a little bit later in this post.

I won’t detail each player’s performance in each of those three glory years — that would be a veritable book in the making, and I don’t want to get bogged down in the minutiae of stats and records and game-by-game analysis. (Instead, more information about them is featured at the end of this post.)

However, I will do so for one guy heretofore unmentioned in this post, the guy whose life arc is, to me, the most fascinating and colorful, and he will now become the focus of this blog installment:

That singular man was named Fred Ramie.

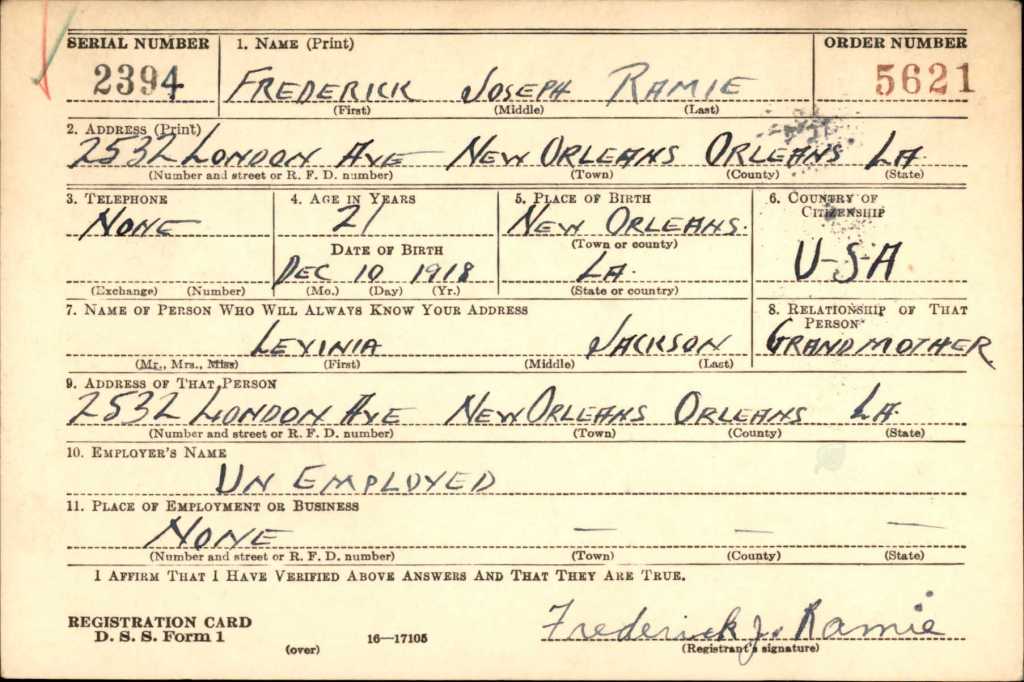

Born on Dec. 10, 1918 (some sources say 1916), in New Orleans to Joseph M. Ramie Sr., a mail carrier, and Leona (Levere) Ramie, Frederick Joseph Ramie had two brothers, August (born two years before Fred) and Joseph Jr. (born six years after Fred), known as Milton. At other points in time, Joseph Sr. was a self-employed beer deliverer, called a drayman; some sources list the senior Ramie as a section hand, or track maintenance man, for a railroad company.

Freddie spent much of his childhood growing up at 1957 Law Street, which was actually just catty corner from Crescent Park, where the New Orleans Crescent Stars played for several years in the 1930s. (The ballpark was one of the first in the city constructed specifically for Black teams and fans; it was the brainchild of the great Pete Robertson, about whom I’ve been researching and writing for a couple years. Check out a couple of my posts about him here and here.)

Freddie apparently started playing baseball as a youth, and by his teens he was suiting up for some of the most prominent Negro League teams in New Orleans, particularly with the Crescent Stars.

In spring 1934, for example, the Louisiana Weekly lists him pitching for the Crescent Stars while still a teenager. The April 14, 1934, issue of The Louisiana Weekly states that he took the mound for the Crescent Stars, who were members of the Negro Southern League) in the second game of a doubleheader against the Chicago American Giants (sometimes referred to as Cole’s American Giants at the time) of the second Negro National League. Ramie seems to have earned the victory in an abbreviated, five-inning game that the Stars won, 4-1. The American Giants won the first game of the DH.

(The doubleheader was part of a scheduled eight-game exhibition series between the two clubs. At that time, the Negro Southern League was generally considered a minor league, and the American Giants were likely playing the Crescents and other minor Southern teams as part of the Giants’ spring training. While the American Giants were past their glory days in the 1920s under Rube Foster, the Windy City club was still good. During the series against the Crescent Stars, four men who would eventually earn induction into the National Baseball Hall of Fame – Turkey Stearnes, Mule Suttles, Willie Wells and Bill Foster – saw action for the Giants, and the team was managed by the illustrious Louisianan, “Gentleman” Dave Malarcher, a disciple of Rube Foster who was 39 in 1934. The Crescent Stars, meanwhile, were stocked with a bunch of local and regional talent. In addition to Ramie, the team boasted manager/outfielder Red Parnell, infielder Tom Muse, pitcher Milfred Laurent and Pepper Bassett, who would eventually earn renown as the “Rocking Chair Catcher.” The Stars were coming off a successful 1933 season, during which they won the NSL second-half pennant and lost to the American Giants in a so-called “world series.”)

Ramie was still with the Crescents Stars a month later, when they hosted the Monroe Monarchs, another NSL team that was based in Monroe, La., a small city in the northeast section of the state. According to the Weekly, Ramie pitched the front end of a doubleheader with the Monarchs; the Stars claimed the first game, the Monarchs won the second. The first contest included a relief stint on the mound by Monroe’s Hilton Smith, who would go on to star in the Negro majors for many years and be inducted into the NBHOF in Cooperstown.

The 1934 Crescent Stars season also included extensive road trips, and Ramie was there for the ride. The Stars’ tour of ’34 brought them, with Ramie, to places like Chambersburg, Pa.; Belmar, N.J.; and even Brooklyn, N.Y.

(Interestingly enough, the Crescents’ barnstorming edition for 1934 also now included Lloyd “Ducky” Davenport, an outfielder from the Big Easy who went on to star in the Black baseball bigtime with several teams, including the Philadelphia Stars, Memphis Red Sox, Birmingham Black Barons, Chicago American Giants and Cleveland Buckeyes. Also on the roster by this time was aforementioned NOLA pitcher Gene Bremer, about local lad who eventually made good in the Negro League big time with clubs like the Memphis Red Sox, Kansas City Monarchs and Cleveland Buckeyes.)

Fred played for a variety of local New Orleans teams in the mid-1930s, including the Jr. Black Pelicans in 1935. I’m not completely sure if the Jr. Pels had any connection to the regular Black Pelicans, but regardless of that, Ramie proved to be a solid pitcher for the Juniors; in July 1935, for example, he pitched the Jr. Pels to an 11-2 win over the Southern Sluggers at Crescent Park, and a few weeks later he took the mound in the Jr. Pels’ 8-6, come-from-behind victory over a team called the Krazy Kats.

But, like many players in New Orleans at the time, Ramie also hopped around from team to team, something evident in the summer of ’35, because in addition to the Jr. Black Pelicans, Fred also suited up for the Algiers Giants. For example, Freddie was unable to hurl the Giants — the premier team on the Westbank of New Orleans — to a win against the Southern Stars, who topped the Giants, 9-7, at Westside Park. That Algiers was fairly stacked, too, with local stars Lionel Decuir, Diamond Pipkins, Dickey Matthews, Tom Muse and Herman Roth as manager.

Another club for which Ramie played was the St. Raymond Giants, a semipro team likely sponsored by St. Raymond Catholic Church.

It looks like 1938 was a pivotal year for Ramie in terms of his development as a world traveler. In April 1938 he was on the roster of the Crescent Stars as a left fielder, joining famous local players like Percy Wilson, George Sias, Raoul “Red” Boguille and Black Diamond Pipkins.

By June, however, Fred had migrated up north to join the Broadview Buffaloes in Saskatchewan, along with buddies Lionel Decuir and Red Boguille.

“Making good in a big way are young baseball players from New Orleans now playing on a Canadian team,” reported The Louisiana Weekly.

“… Ramie and Bougille [sic] alternate in pitching and fielding,” the paper added. “Both have been running up great records as pitchers and due to their efforts, their team, the Broadview Buffaloes, are now leading the Southern League in Canada and seem headed for a pennant.”

The paper noted that Ramie had pitched a 12-inning, 8-7 win for the Buffaloes, and The Weekly noted that all the Louisiana lads “are pounding the apple hard for extra base hits and are well liked.”

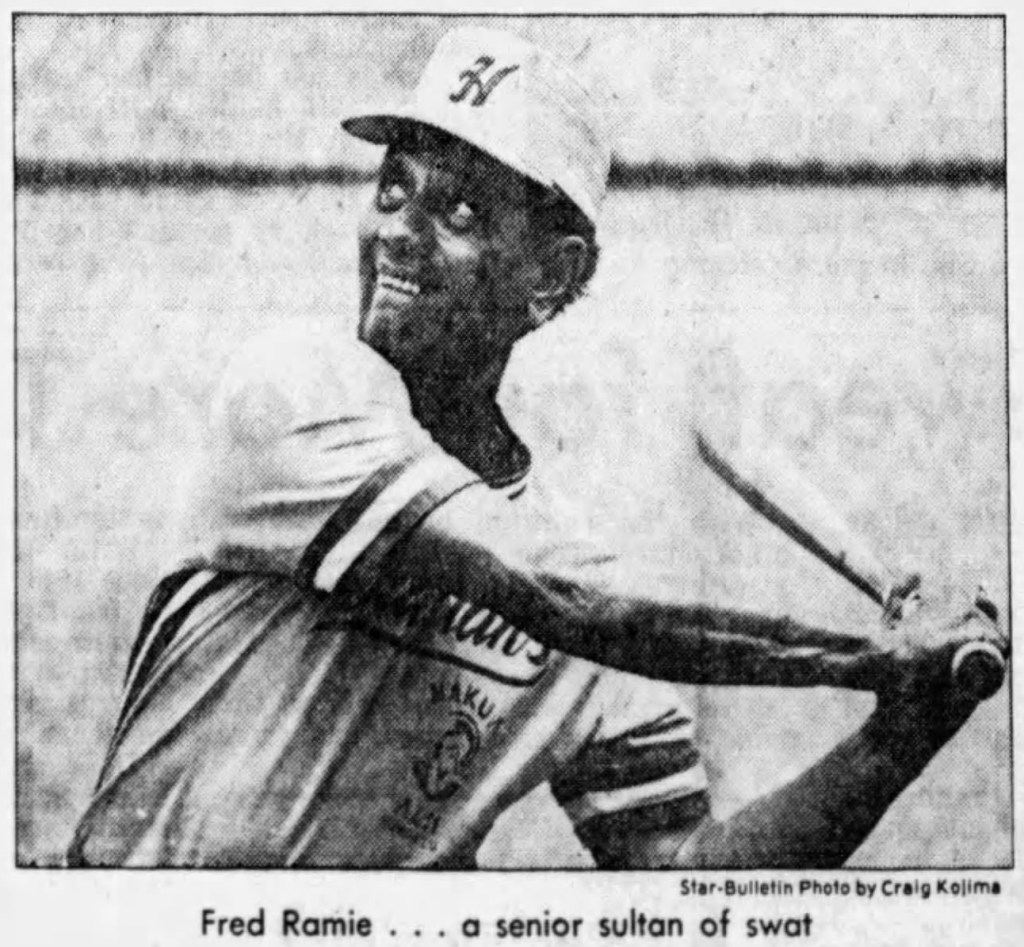

The Louisiana Weekly then reported, in its Aug. 6, 1938, issue that Fred was still shining for the Buffaloes. Under the headline, “Freddie Ramie makes good on Canada team,” the paper stated that Ramie was “enjoying a brilliant season as a pitcher for the Broadview Buffs in Canada. He has compiled the good record of 9 wins, 3 losses and two ties.”

Saskatchewan newspapers have Ramie, along with Boguille and Decuir, playing for the Buffaloes as early as late May; fellow Louisianian George Alexander also eventually joined that trio in Broadview that season.

The June 18 issue of the Regina Leader-Post reported that Ramie pitched well in a tough, 3-1 loss to the Regina Army and Navy Senators, stating that “Lefty Ramie did a neat job of chucking for the Buffs and gave up only seven hits altogether to play a big part in the best game of the season …”

On June 22, the Broadview battery of Ramie and Decuir helped the Buffaloes win the annual exhibition tournament in Watson, Saskatchewan; the Buffs came out on top of the 16-team fray.

When he wasn’t on the mound, Ramie held down left field for the Buffs admirably.

The Buffaloes ran away with the championship of the Southern League (located mainly in the province of Saskatchewan, it looks like), thoroughly overwhelming the other teams in the circuit and prompting some observers to grumble that Broadview was so good it shouldn’t have been in the league. The Louisiana-laden Buffs also played a bunch of exhibition games that season, including several holiday tournaments and some showdowns against barnstorming Negro League teams. (For a more detailed rundown of the Buffaloes’ years with the Louisiana players, check out my earlier post.)

In August 1938, following the end of the season on the Canadian Plains, Ramie and fellow New Orleanian George Alexander returned to the Big Easy to play for Fred Caulfield’s Jax Red Sox semipro team, a stint that included what The Louisiana Weekly dubbed a city/state Negro championship series with the New Orleans Sports.

Fred continued his career in baseball during the ensuing few years, mainly in New Orleans. In 1939, he began the season with the semipro New Orleans Sports, who were managed by Clarence Tankerson (who was an important figure on the city’s Black baseball scene for many years) and also featured Lionel Decuir catching.

Interestingly, as a side note, in April 1939, Louisiana Weekly sports editor/columnist Eddie Burbridge reported that “Freddie Remy [sic], local hurler, may go to California soon to slam ’em over the plate for a West Coast ball club. May pitch in Texas first.” However, I haven’t had a chance to really look into whether Fred actually took advantage of such far-flung options.

Regardless, by mid-spring, Fred had jumped to the Jax Red Sox, and by the end of the season, he’d hooked on with the Shreveport Black Giants, who were piloted by the great Winfield Welch.

During the middle of the 1939 campaign, however, Fred had a chance to return to the Canadian plains, courtesy of the just-mentioned Winfield Welch. Because on this new journey north, Ramie didn’t suit up for the Broadview Buffs or any other Canadian teams – he came as a member of the Crescent Stars, who undertook an extensive barnstorming trek that brought them to the Great White North.

This version of the Crescent Stars was piloted by Welch, who probably recruited Ramie and the rest of the roster to undertake the epic road jaunt around the continent. Such barnstorming tours were nothing new to Welch, who a few years earlier had led an aggregation called the Shreveport Acme Giants, who were another mostly-on-the-road team that also wound its way north, traversing the U.S. Midwest and entering into Canada. Some of the players from that Acmes team – including Gene Bremer, Red Boguille and Lionel Decuir – were among the group of New Orleanians who ended up jumping to the Broadview Buffalos and other Canadian teams.

In 1939, though, it was as a New Orleans Crescent Star that Fred Ramie crossed the northern border into Canada. The rambling team played several games in Saskatchewan and Alberta. One of Ramie’s best mound performances on the jaunt was a July 9, 1939, clash with the similarly barnstorming aggregation, the famous House of David team, who were based in Michigan at a religious commune. Ramie pitched three-hit ball in the Stars’ 4-0 victory. The game was held in Edmonton, Alberta.

Unfortunately, Fred wasn’t as fortunate in a return game with the Davidites in Edmonton two days later – he had to exit the game in the sixth inning after suffering an injury two days earlier.

After criss-crossing the Canadian Plains, Ramie and the Crescent Stars made a bunch of stops for more games in the States as they apparently made their way back to the Big Easy, including places like Albion, Wisc.; Belleville, Ill.; Charles City and Clinton, Iowa; and Escanaba, Mich.

(For this stretch of play, Ramie often played in the outfield on days he didn’t pitch, a trend he began and continued through much of his career.)

It appears that when the Welch-led Crescent Stars returned to Louisiana from their extended travels, Welch turned them into another version of the Shreveport Giants for the remainder of the season, and Ramie was along for the ride.

In 1940, Ramie played for the Algiers Giants, a powerful, long-standing Negro Leagues team based across the Mississippi River on the Westbank. Also on the team was Big Easy baseball legend Wesley Barrow, who anchored the Westsiders behind the plate. That season, Ramie also pitched a little bit for another Westbank club, the Tregle Pets.

Freddie continued with the Algiers Giants for the following two seasons, when the club was sponsored by the Dr. Nut company, which produced a popular soft drink. The Algiers club also featured Eugene Bremer, as well as two young prospects who would go on to greatness by breaking into the Black baseball majors – Herb Simpson and J.B. Spencer. Lionel Decuir also played for Algiers at this time.

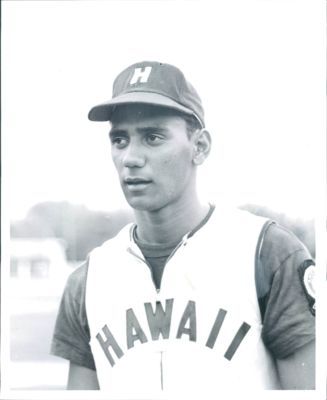

Ramie seems to have left New Orleans for Hawaii in the mid-1940s; he first appeared in the Honolulu media as a ballplayer in 1943 and married his first wife, Lily Kealoha Kamana, a native Hawaiian, around the same time the same year. They had their first child, son Ronald Joseph Ramie, a little more than a year later.

But before we delve into Fred’s life and career in the 50th state, it’s important to give a rundown on the history of baseball on the islands, beginning with the military teams composed of U.S. soldiers and sailors stationed in Hawaii.

Another significant part of Hawaiian hardball history is the Hawaiian Winter Baseball League, a short-lived – it existed from 1993-97, and from 2006-08 – minor circuit somewhat similar to other winter leagues like the integrated California Winter League (1910s-1940s); the famed Cuban League (1878-1961), where white, Black and Latino talent flocked in the winters to form some of the greatest baseball teams of all time; the Puerto Rican Winter League, founded in 1938 and still going today; Jorge Pasquel’s renegade Mexican League (1940s); and other circuits in Latin America.

While the Hawaiian Winter League didn’t have the historical significance of those early leagues, it still proved a popular entity in Hawaii and attracted talented then-prospects like Todd Helton, Jason Giambi, Buster Posey, Aaron Boone and Ichiro Suzuki.

MLB.com writer Matt Monagan gave readers a reflective look back at the Hawaii Winter League, including quoting former Hawaiian Winter Baseball League owner Duane Kurisu.

“We carried a vision that went beyond baseball. …,” Kurisu said. “We felt that our role could be to develop the tools of Aloha, which included characteristics like trust, confidence, character and community.”

There was also the Hawaii Islanders of the Triple-A Pacific Coast League. The squad existed from 1961-87 and maintained affiliations with several major league clubs, and it won the PCL titles in 1975 and ’76 as the top farm team of the Padres.

The PCL franchise began as the Sacramento Solons, who moved to Hawaii in 1960 to become the Islanders. They ended their 27-year existence in the 50th state prior to the 1988 season, when they moved to the mainland to become the PCL’s Colorado Springs Sky Sox. (The franchise currently exists as the Double-A San Antonio Missions in Texas.)

“But in between their coming and going,” wrote Hawaii Advertiser reporter Stacy Kaneshiro in 2009, “the Islanders brought a lot of memories.”

Noting the roller-coaster existence of the team, both at the turnstiles and on the field, Kaneshiro added that “[i]n their heyday, the Hawaii Islanders were like the opening [of] Dickens’ ‘Tale of Two Cities’: The best and worst of times.”

Then there’s the Hawaii AJA Baseball Association, a network of amateur leagues based on each island of the state. Founded way back in 1908, the AJA still thrives today, with the Maui All Stars winning the 2023-24 state championship, their second in a row.

The AJA perhaps represents the multiculturalism and ethnic diversity of Hawaii, with the organization uniting players and teams from just about every background – Native Hawaiians, Polynesians, Japanese, Chinese, Filipino, Portuguese, and Black and white ones from the mainland.

While the AJA – formally known as the Hawaii State Americans of Japanese Ancestry Baseball Tournament – began more than a hundred years ago as a baseball outlet for Hawaiians of Japanese descent, it has since blossomed into a prestigious yearly event that brings together baseball-loving Hawaiians of all ethnic backgrounds. Reporter Bart Wright wrote in a 2019 article for the Hawaii Tribune-Herald:

“Baseball has forever been popular on the Big Island, but the community structures they knew back before World War II, the leagues, ballparks, the games themselves, are mostly all gone, if not forgotten.

“‘We had so many different ethnic groups and they all wanted to play baseball,’ said Royden Okunami, president of the Hawaii entrant in the four-island AJA baseball league. ‘Every (sugar) plantation had their own team, with everyone eligible, no matter where you came from, but then they also had a Chinese team, Filipino and Portuguese teams, and, of course the Japanese team.’”

Wright also quoted an AJA administrator, Curtis Chong: “All these things that occurred in the past, the plantation lifestyle, the laborers in the fields being the ballplayers, the way they formed the leagues so they could play, all these things we represent in a living memorial. We could have put up a monument, but instead, we have a living memorial, something that keeps building on itself, honoring the past in the present.”

So where does Fred Ramie fit into all of this?

It appears as though Fred moved to Hawaii in the 1940s, well before the territory was admitted to the union in 1959, and he wasted no time in immersing himself in the islands’ baseball scene.

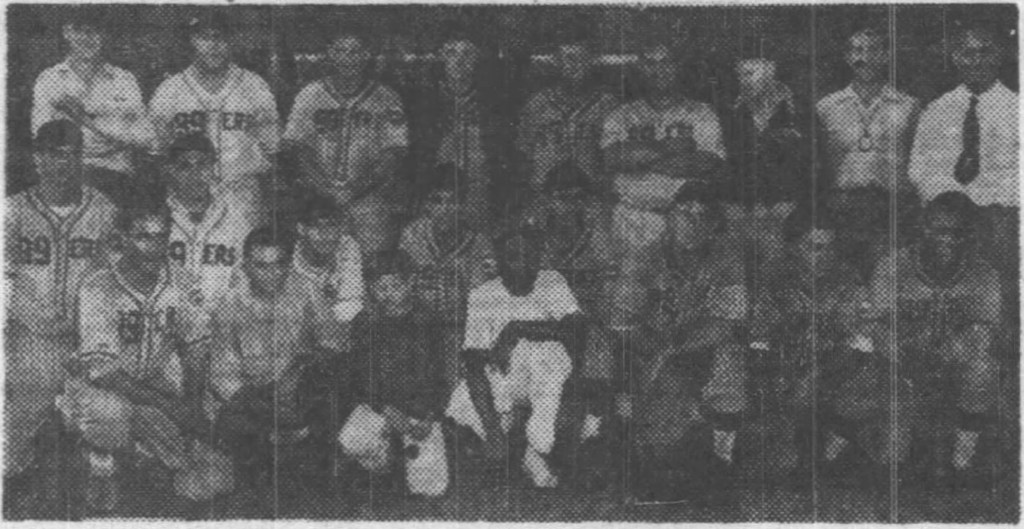

In the spring and summer of 1943 – roughly two years into the U.S.’ involvement in World War II – Ramie took part in the newly organized Pearl Harbor Civilian Baseball League, made up of employees and other civilian members of the Naval base community. Ramie played for the Shop 99 team, which was composed of workers with the Ship’s Service and Maintenance division, and he helped guide the squad to the league championship that inaugural year. Fred swatted two home runs and was picked for the left field spot on the league’s first-team all-star lineup.

For several ensuing years, Freddie Ramie suited up for the Pearl Harbor Civilians’ Navy Yard team in various leagues in and around Honolulu; in 1946, while playing for the PHCs in the Federal Employees baseball league, Ramie earned all-star team honors as an outfielder.

In 1947, it appears that the Honolulu Baseball League was sort of shoved out of the spotlight on the islands by the relatively new Hawaii Baseball League, and Ramie and many of his teammates and peers made the jump between leagues. Ramie, who’d already gained a fair amount of attention from local baseball connoisseurs, competed for the reigning HBL champion Braves team as an outfielder. Unfortunately, in July ’47, Fred broke his collarbone, hampering his participation in the rest of the season.

Two years after that, Fred played for the unfortunately-named Injuns team in the annual Hawaii Baseball Congress tournament in spring 1949, and he ended up winning the tourney’s batting championship, going 10 for 20 for an average of .500.

Over the next several seasons, Ramie transitioned from outfielder to pitcher, climbing the hill regularly, just like he did in the 1930s and early ’40s for various African-American teams in Louisiana and beyond. When taking the mound for the Tigers team in the HBL at that time, Fred was used mainly in relief.

By 1957, a new circuit had come together, the Puerto Rican Baseball League, operated by the Puerto Rican Athletic Association, and Fred Ramie was part of it, playing for the Kondo team. In ’57, the PRBL ran from January to April, and Fred made the most of it by winning the batting triple crown, hitting at an eye-popping clip of .571 and driving in a league-leading 12 RBIs, while tying for the league home run tallies with two.

Ramie repeated as PRBL batting champion in 1958 with a mark of .526 while playing for the Kondo Auto Paint Shop team. He also smacked three homers, drove in 18 runs, slashed 30 hits and clubbed seven doubles, the latter two figures also leading the league. Two years later, Ramie signed on as the field manager for the Rican Giants team, and in 1962 he served as the league’s vice president and returned to the top of the PRBL batting heap in by swatting a league-leading .538 on 14 hits in 26 at bats for the Rican Giants.

By the early 1970s, Freddie, then well into his 50s, was coaching his children in local baseball leagues. In 1972, he coached the Maka-Pointers team to the State Senior Little League championship; the aggregation included Fred’s son, Vernon Ramie, a 13-year-old lefty, who won the title game, 7-0, over the Kainalu team, striking out 11 and allowing only two walks.

But just because Fred was now immersed in coaching newer generations of baseball fans, doesn’t mean he himself quit playing on the diamond. Later in the ’70s, Ramie excelled in the senior softball community. His club, named simply the Hawaiians, won the Hawaii state senior softball championship. At the conclusion of the 1979 season, Freddie was named circuit MVP, an accomplishment he repeated in 1983 while leading his team to its fourth straight Hawaii Senior Citizen Softball crown.

Two years later, Freddie co-coached the island of Hawaii’s team to the Seaweed Kealoha Fall-Winter Slow-Pitch League championship.

While living in Honolulu, Fred worked as a civilian electrician at the Pearl Harbor Naval Shipyard; a 1944 news articles reported that Ramie, at the time an electrician third class, was one of 15 people who received a commendation for their role in salvaging ships that were sunken or damaged in the devastating attack by the Japanese on Dec. 7, 1941, that pulled the U.S. into World War II. He also worked for the City and County of Honolulu.

Ramie had four children in Hawaii ii in addition to his first child, Ronald; the other kids included son Vernon (Vern) Ramie, and daughters Leimomi Ramie (later Ronstadt post-marriage) and Michele. (More on Vern and Ronald in a bit.)

Fred lived in several areas in Honolulu – which is on the island of O’ahu – during his life. The 1950 federal Census, for example, lists him on N. King Street (keep in mind that Hawaii was still a U.S. territory in 1950, nine years before it became a state).

(Interestingly, the document also lists Ramie as Puerto Rican, although I haven’t been able to find any information or detail on the Ramies’ exact cultural heritage, besides that both of Fred’s parents were born in New Orleans. In the 1930 Census taken in the Crescent City, Fred and his parents are listed as “Negro,” but the 1950 Census states that Fred was Puerto Rican.)

When Fred first got married, he lived on Waialae Avenue, the main street in the Kaimuki neighborhood. (Kaimuki eventually became where Chaminade University of Honolulu is located, having been founded in 1955. College basketball fans might recognize Chaminade as the host of the annual, midseason Maui Invitational tournament. Kaimuki is also the location of Kapi’olani Community College.)

The Ramies also lived on Leilani Street, located in Honolulu to the northwest of Kaimuki and closer to Pearl Harbor in the Kalihi neighborhood. (Kalihi is the home district to Tulsi Gabbard, who served in the U.S. House of Representatives from 2013-2021 and was the first Samoan-American and first Hindu to serve as a voting member of Congress and is currently a leading candidate to join Donald Trump’s 2024 campaign ticket as the vice presidential nominee.)

Finally, Fred and family lived on Awawa Street in the Wakakilo neighborhood in the planned community of Kapolei, which is informally dubbed “the second city of O’ahu,” even though it is technically located in and governed by the city and county of Honolulu. It’s also near the historically vital and culturally rich Ewa Beach, on the southern shore of O’ahu to the west of Pearl Harbor.

By an unfortunate turn of bad luck, the Ramies’ home at this address was destroyed by a fire in 1973; according to news reports, the fire was caused by children playing with matches, with the blaze doing $42,000 worth of damage. Luckily, no one was hurt.

Frederick Joseph Ramie passed away on Jan. 15, 1999, at the Kaiser Foundation Hospital in Honolulu. His obituary in the Honolulu Advertiser newspaper called him an “all-star baseball player with Hawaii Major League, Puerto Rican League and Makule League.”

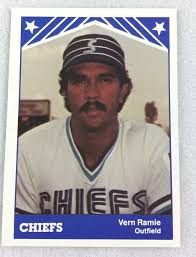

Another way Fred Ramie built his lasting legacy is through his family, teaching his kids to love the sport of baseball as much as he did. That imparting of diamond knowledge took hold most in his son, Vern Ramie, who was born in Hawaii in 1958 to Fred and Lily.

Vern, a first baseman/outfielder, excelled in the game so much at Kamehameha-Kapalama High School that he earned a spot on the University of Hawaii team, then went on to play in the minors for a few years in the 1980s, suiting up several teams in the Toronto Blue Jays system — who took him in the 12th round of the 1979 draft — including the Knoxville, Tenn., Blue Jays (Double-A Southern League, currently the Tennessee Smokies); Kinston, N.C., Eagles (Single-A Carolina League); and the Syracuse, N.Y., Chiefs (Triple-A International League, now the Syracuse Mets.)

For his cumulative minor-league career, Vern hit a very respectable .275/.401/.456, with 50 round trippers, 77 doubles, 13 triples and 233 RBIs. He scored 214 runs, swiped 16 bases and posted excellent fielding percentages of .993 as first base and .964 in the outer garden.

(His teammates in the minors included future major leaguers Jimmy Key, Tony Fernandez, George Bell, Mark Eichhorn and Jesse Barfield.)

After retiring as a player, Vern remained in the game and, like his father, has spent many years passing on his knowledge and love of the game, especially at Kamehameha-Kapalama High School, his prep alma mater, where he piloted the team to five state title games and seven state semifinals, winning it all in 2003 for the state championship. In a coaching career that ran from 1991-2013, he also skippered the school to five Interscholastic League of Honolulu titles.

In 2013, Vern Ramie also received the Chuck Leahey Award in 2013, given to a person who has made significant lifetime contributions to the sport of baseball in the state of Hawaii.

Aside from his high school coaching career, in 2014 Vern co-founded the 808 Baseball Academy, where he and the other staff tutor and coach young men and women from Hawaii, Japan and the Mainland in baseball and softball. The academy — which also features Honolulu native, former New York Met and Nippon Professional Baseball standout Benny Agbayani — hosts hopeful baseball stars at its field and facility in Waipahu.

As further evidence that the Ramie family had baseball running through its veins, Vern’s older brother, Ronald, who was born in 1944, enjoyed a few years in the San Francisco Giants farm system in the 1960s, including stops in Lexington, N.C.; Salem, Va.; and Decatur, Ill.

Way back a couple years — this post has been on the burner for too long — I tracked down Vern Ramie and interviewed him over the phone about his father and the ways Fred Ramie influenced Vern’s own career in the national pastime.

“Baseball is a way of life in the Ramie family, all generated from him,” said Vern, who added that Fred coached his kids in the Hawaii Little Leagues. “Baseball is in our DNA.”

In fact, both Ronald and Vern filled out questionnaires for a study by William J. Weiss, a publisher and statistician based in San Mateo, Calif. The forms assessed the complete baseball careers of each study participant, from youth, high school, college to professional.

On his questionnaire, circa 1980, Vern Ramie lists his positions as first base and outfield, and that he started with the Makakilo Little League and the Waipahu American Legion. He attended and played for Kamehameha High School, where lettered in football and basketball in addition to baseball, before heading to the U. of H., then the semipros and pros.

When answering the question of his greatest thrill in his baseball life, he wrote:

“My biggest thrill was playing for the USA All-Star team in Japan in the summer of ’79. We lost [their] first 3 games then came back to win the next 4 to win the series.”

On Ronald Ramie’s questionnaire, dated 1963, Ron states his position as outfield and that he attended and played baseball, plus football and track, at Farrington High School. He also participated in the police activity league and American Legion baseball.

Ronald wrote that his most interesting experience in high-school or college baseball was seeing a high-school teammate club four home runs during the state high-school playoffs. His personal goal for himself was “[t]o play Big League baseball someday.”

To the question of his “most interesting or unusual experience” from throughout his entire tenure in baseball, he listed a game from the previous summer in which he smacked two homers and drove in seven runs in the American Legion regional playoffs.

By the time Vernon was born in 1958, Fred had already been in Hawaii for well more than a decade, and the elder Ramie rarely reflected on his baseball roots in New Orleans or in Black baseball, his son said.

“He didn’t talk a lot about his playing time in New Orleans,” Vern told me. “He never really went into a lot of detail about it.”

However, Fred was extremely proud of his hometown and stayed close with his relatives in the Big Easy.

“He loved it there,” Vern said. “All of his family was still there, and he still went back to see them. He tried to get back as frequently as he could, maybe one or two times every year. I always remember how happy he was to come home and see everyone.”

(Vern noted that there’s less members of the Ramie family still in New Orleans; many of them left during Hurricane Katrina and decided not to return.)

Well, that’s the story of Fred Ramie, the man who traversed the North American continent over the roughly six decades he spent in the sport of baseball. From segregation in New Orleans to the lonely prairie in Saskatchewan to the sun-kissed sand of Hawaii, Fred spent his life lacing up his spikes for dozens of teams on various levels of play. In the end, I’d say, he represented his hometown very well, showing folks across the continent what a N’Awlins kid could do on the diamond, and he, perhaps best of all, passed that passion for America’s pastime down to his own kids.

Postlude

While this post focused on Fred Ramie, I feel bad giving short shrift to some of the other local lads who played for the Buffaloes, because each one of them is fascinating in their own right. The life and career of Gene Bremer has been fairly well documented, largely because he’s the one who had the longest, most illustrious career in the Negro big leagues, so I’ll suggest the comprehensive compendiums of him and his career here and here for more information.

Thus, here’s a short rundown of the additional Louisianians in Saskatchewan:

Lionel Decuir, while not as illustrious as Bremer, enjoyed a decent career in the top-level Negro Leagues, including two as a backstop with the Kansas City Monarchs in 1939 and 1940; he received tens of thousands of votes in fan balloting for the East-West All-Star game each of those seasons. He also suited up for the South team in Allen Page’s annual North-South All-Star game in New Orleans.

A native New Orleanian, Decuir played locally in the Crescent City with the Caulfield Red Sox, New Orleans Black Pelicans, the Algiers Giants, the New Orleans Sports and the Dr. Nut Tigers (yes, that’s the real name, from the team’s corporate sponsor, the Dr. Nut soda company), among other clubs. Decuir also played quarterback for the Brutes team in New Orleans’ semi-pro sandlot football league.

Boguille, from what I can tell, never broke through to play with teams in either the Negro American or Negro National League, but he likely played against those top-level aggregations when they journeyed to New Orleans, either as part of spring training in March and April, or post-season barnstorming tours in September and October. He seems to have been a few years older than the other New Orleans lads who went to Saskatchewan, having started his semi-pro/pro career in the Crescent City in the early 1930s. In the years in the Big Easy before his time in Saskatchewan, Boguille hurled for the Rhythm Giants, the Crescent Stars, the Algiers Giants and the Caulfield Ads, as well as the Shreveport Acme Giants. (More possibly to come about the barnstorming Shreveport Acme Giants and the way they served as a conduit for Louisiana players to pass through from New Orleans to Broadview.)

I wasn’t able to really dig much into the story of George Alexander; I just never had the time to root around for his, umm, roots. But I know he did frequently lace up the spikes locally for the Jax/Caulfield Red Sox, a team managed by businessman and N’Awlins baseball mogul Fred Caulfield and sponsored by the Jax Brewing Co., proud makers of Jax Beer, a Big Easy favorite. His peak with the Red Sox came between 1939-40, and, according to a 1944 Chicago Defender dispatch, Alexander turned down an offer to join the Cleveland Buckeyes in favor of signing up for the Army, advancing to corporal and serving in New Guinea in 1944.