With my previous post, about New Orleanian turned Hawaiian Fred Ramie, I’m going to try, at least through the end of the year, focusing this blog on the history of Black baseball in New Orleans and Louisiana.

I’m also going to attempt to keep posts much shorter than I have been over the last few years. While 6,000-word diatribes can be very valuable and needed for certain subjects, I also know that there’s only so much material that readers should be asked to slog through over and over again.

One of the reasons for the shift in focus is how, over the last several months, I’ve been going through microfilm of the Louisiana Weekly archives from various years, and I’ve been finding a treasure trove of cool stuff that I really want to write about and to bring to my readers.

And one of the historical trends I’ve noticed is the formation, and attempted formation, of all kinds of locally based leagues, playoffs and competitions on a city, regional and even interstate level.

I’ll start exploring that theme with the year 1944 (80 years ago) when at least four such organized competitions took place, beginning with the one most fascinating to me – the Inter-Project Athletic League, in which four housing projects throughout the city of New Orleans competed against each other, including softball.

America’s first public housing projects – which were designed to replace slums with new, subsidized apartment buildings for low-income residents – were actually built in New Orleans in the late 1930s and early 1940s. In 1941, four segregated developments, or projects, for the city’s Black residents were officially opened – the Calliope, Lafitte, St. Bernard and Magnolia developments.

Here’s how journalist Roberta Brandes Gratz described the early New Orleans projects in the June 22-29, 2015, issue of The Nation magazine:

“New Orleans was one of the first cities in the country to get public housing, with six projects in place in the early 1940s. These were solid, well-crafted brick structures of three to five stories, often with tile roofs, front-entrance grillwork, solid wood floors, and separate entrances for small clusters of apartments. Many of them stood around courtyards with shade trees and paths. As a style, they became the model for the many private garden apartments that followed.”

The Calliope Projects were located along what is now Earhart Boulevard in Central City, more or less a stone’s throw from the area that would eventually house the Superdome. The Magnolia Projects were located in the Central City neighborhood, to the west of downtown. The St. Bernard Projects were located in Mid-City, with Bayou St. John and what is now City Park to the west, Dillard University to the east, and the Fairgrounds close by on the south. The Lafitte Projects were located in the famed Treme neighborhood, bordered by the French Quarter to the immediate southeast.

Together, these “big four” New Orleans developments housed thousands and thousands of residents – enough for each projects to form its own softball team. And within just a few years, these teams, representing neighborhood pride, joined to create the Inter-Project Athletic League in June 1944.

According to the July 1, 1944, issue of The Louisiana Weekly, “[T]he purpose of the League is to stimulate wholesome interest in all forms of athletics and to develop a closer inter-project tenant relationship.”

I discovered this nugget of softball competition while combing through the archives of the Louisiana Weekly from 1944. The league launched during the summer of that year with four teams – the Lafitte Tigers, the Magnolia Greenies, the St. Bernard Grays and the Calliope Patriots.

Each team had its own “home grounds” baseball/softball diamonds – on expansive playgrounds – with games shuffling among the four, mostly on Sundays.

The Louisiana Weekly reported that “[a]dmission to all games is free, so show good will [sic] and let’s have a crowded park at all games at all times.” The July 15, 1944, issue of The Weekly, in reporting on the Tigers’ 7-3 win over the Greenies, and the Grays’ 5-0 triumph over the Patriots, stated that “[b]oth games were played before a very large and enthusiastic crowd.”

The July 22 edition of the paper included an article covering the previous weekend’s game.

“The crowd was very large at both games,” the article stated. “For a very good evening of enjoyment and good softball playing [,] visit the playgrounds where there is a game between two of the Inter-Project league teams.”

The league recruited leading activists and educators to guide the organization. Selected as the first president of the league was Sheldon C. Mays, a teacher first at the private Gilbert Academy and then at a public school, Valena C. Jones Elementary.

Mays was also a prominent community leader, giving speeches and school graduations, serving as a field executive for the Boy Scouts, and chairing community committees and organizations that advocated for fair housing and the advancement of Black leadership in New Orleans.

Mays also served as the assistant manager at the Lafitte Project, then as manager of St. Bernard and Calliope in succession.

Also brought on board to provide stability and exposure for the new Inter-Project League was Clement MacWilliams, a prominent Civil-Rights reporter for The Louisiana Weekly. “Mac,” as he was known by many in the city, was also a Boy Scout leader and a youth mentor at both the Magnolia development and the New Orleans Recreation Department.

MacWilliams’ role in the community, especially his experiences as a reporter and writer, made him a natural choice to help lead the softball loop, primarily by doing media relations and public outreach, including a column in The Weekly during the league’s second season in 1945.

While I haven’t been able to delve into this topic in depth like I’d ideally want to, the Lafitte and St. Bernard clubs were the class of the 1944 Inter-Project Athletic League, with those two battling for first place all season.

Each team seems to have had an ace pitcher who could completely shut down opponents’ lineups during any given game. The Patriots, for example, had Jessie Madison, who hurled a no-hit, no-run gem against the Greenies, while the Tigers went to battle with “Bo” Augustine and “Gummy” Williams able to put the clamps on their foes.

The season wrapped up in late summer with a pair of barnburners between the two top clubs, St. Bernard and Lafitte. First, on Aug. 27, in what The Weekly dubbed “one of the greatest battles of the sport season,” Lafitte edged St. Bernard, 4-3, in 11 innings at the Grays’ home field. The narrow triumph vaulted the Tigers into first place with a 7-3 record, topping the Grays’ 6-2 mark.

However, St. Bernard turned the tables on Lafitte with a 6-5 triumph in the de facto title game, held at Calliope Playground on Sept. 17.

Following the end of the season, an all-star team was chosen by the public from the three other teams in the inter-project league.to play a postseason game against the champion Grays, xxxxxxx won that contest, xxxx.

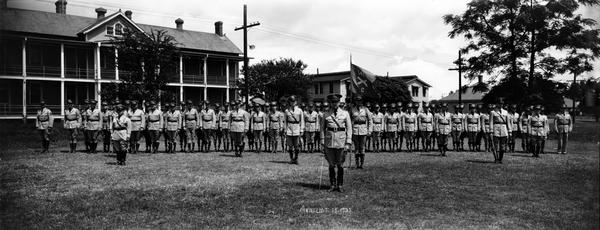

The League enjoyed its second season in 1945, with a couple of major modifications. First, a fifth member was welcomed into the circuit – the Jackson Barracks, which has been the headquarters of the Louisiana National Guard for nearly two centuries.

Located in the Lower Ninth Ward of New Orleans, Jackson Barracks, at the time of the Inter-Project League, had shifted to temporary federal control and became an outpost and point of embarkation for soldiers being shipped overseas.

But in terms of the city’s housing projects, the admission of Jackson Barracks into the Inter-Project League proved disastrous, athletically speaking. The Guardsmen claimed the regular-season pennant at 6-1 and played 4-2 St. Bernard, the 1944 champ, in the title game.

The championship clash proved to be no problem for the military men, who crushed the Grays, 5-1, on July 29, 1945. The Weekly stated that “[T]hose orange clad clouters from Jackson Barracks gave an exhibition last Sunday of some of the best slugging of the year.”

That brings up the second significant adjustment for the Inter-Project League’s second season – the projects teams played squads from other community organizations and local businesses throughout the season, mostly as exhibitions. And while the housing teams played their schedule, a separate city league composed of independent squads was playing.

Among these independent teams were Foster’s Chicken Den, the Harlem Crusaders, the Southern Knights of Labor and Toni’s Tavern, but it was the Club Crystal squad from the 20th Century Athletic Club, as the best independent squad in the city, that trounced the Jackson Barracks aggregation, 7-1, at Lafon Playground. According to The Weekly, nearly 3,000 fans turned out to see the title game on Aug. 5.

Following the city championship showdown, the Club Crystal team on Aug. 25 squared off against an all-star team made from various players from each of the five Inter-Project League clubs; the Crystals won that game, too, this one by a count of 8-1.

Throughout the 1945 softball campaign, MacWilliams contributed a periodic softball highlights column in The Weekly, and after the lid was closed on the 1945 summer softball season, his newspaper piece reflected on the season that was, with a particular focus on his hope that Inter-Project athletic training and competition could provide the city’s young men – the ones fighting the war abroad and the ones who remained home – with the type of structure, discipline and physical activity that might make those men stronger and more equipped to contribute positively to society.

“I have been doing a great deal of thinking,” MacWilliams wrote in a regular softball column the newspaper, “about the future of our boys, the ones that are home and the ones that will return. Much can be done for them if the ones who have the power would only do something. I, personally, love sports, most any kind and will do whatever I can to help the game. If any attempt is made to improve conditions for our boys you can bet your life that I will be in there pitching.”

“Mac” also listed eight developments or changes that he would have liked to see if and when inter-project and intra-city play kept going. Among this eight-point wishlist were local businesses taking more of an interest in local sports through team sponsorship or other bottom-line boosting support; seeing more young women take up sports; and creating and construction a “Negro Recreation Center” in the city.

For the purposes of this blog, the individual desire from MacWilliams’ list that carried the most significance for the city and its Black residents and businesses was increased involvement in young adult recreational sports by the city’s semipro and pro baseball managers in young men’s sports, especially softball and baseball. Wrote MacWilliams:

“I would like to see the Negro baseball managers take an interest in our youngsters. These boys are the future teams but they need plenty of help from those who know baseball.”

I’m not sure if the Inter-Project Athletic League remained active in the years after 1945, and if so, how much and for how long. I didn’t have a chance to look much beyond the ’45 season.

Unfortunately, by the 1980s, the Crescent City’s housing projects had largely deteriorated and become rife with crime, with much of the strife the product of gang violence, the crack cocaine and AIDS epidemics, and the devastating effects of Reaganomics. In addition, by that time the city’s projects had become inhabited almost entirely by people of color, a dynamic that reinforced the racial and class segregation and stratification that captured African Americans in the same cycles of poverty that the projects were supposed to eradicate in the 1940s.

When Hurricane Katrina came through in 2005 and destroyed much of the city, many of the projects’ buildings had been closed or razed; Katrina effectively finished off what were innovative and influential public-housing developments.

Within a few years after Katrina, the vast majority of all the buildings in the “big four” developments were torn down and marked for redevelopment. In their place came brand new, grant-funded, government-backed developments, including mixed-income and mixed-use housing, such as townhouses and other dwellings. Whether such post-Katrina housing efforts have worked in improving life amoung disadvantaged communities remains up for debate.