Black baseball history is, shall we say, fraught with complexity, nuance and the blurring of the lines between unique and ostentatious, creative and exploitative.

In a sport and a society that segregated ethnicities, relegated people of color to the sidelines and the shadows, and wielded hate and injustice as (often lethal) weapons, Black baseball players, managers, executives, journalists and fans often had to scrimp, save and scratch out a living. Teams and their owners were virtually forced to use creativity, flexibility and daring to find success and financial survival.

And sometimes, well, that led to some pretty ugly, embarrassing solutions and situations, ones that, out of fiscal desperation, exploited racial stereotypes and demeaning antics to maintaintain solvency and relevance.

That was certainly the case in New Orleans, where, perhaps more than any other community in America, blended, mixed and muddled the boundaries of race, class and ethnicity. This was, and is, a city known for its boisterous, bacchanalian celebration of Mardi Gras in a weeks-long, city-wide party that culminates with one club’s fabled parade of marching men wearing blackface and tossing coconuts to the hollering throngs that line the streets.

The annual Zulu club’s parade embodies both the joie de vivre of an entire city and the tangled, thorny, delicate historical and sociiocultural balance and backdrop in which New Orleans’ multihued, multicultural population lives and quite often thrives.

Now, enter one of New Orleans’ most peculiar baseball ventures ever – the Jax Zulo Hippopotamus.

Quite likely modeled on the Zulu Cannibal Giants – a largely barnstorming club that traveled the country and that had several different iterations in the 1930s and ’40s. The Giants exploited racial and cultural stereotypes of Africa and Africans to elicit laughs while playing decent baseball. Their schtick included wearing blackface and other face paint, putting on grass skirts, playing barefoot and adopting ridiculous “African tribal” names like Limpopo, Nyassess, Taklooie and Wahoo.

In an example of how tangled and scattered the Zulu Cannibal Giants’ story was, one version of the team was actually purchased by two New Orleans entrepreneurs, Ernest Delpit and Charles Henry, who moved the club’s base of operations from Schenectady, N.Y., to the Big Easy in 1936 and used the Lincoln Park ballfield as a home grounds for the Giants.

Now, whether there’s any tangible connection between the 1930s Zulu Cannibal Giants of New Orleans and the Zulo Hippopotamus is unclear, and I haven’t had the opportunity to explore the complete history of the former. (Also unknown is any possible connections between either team and the famed Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club and its hugely popular Mardi Gras krewe and parade.)

However, the two teams’ M.O.’s were very similar in terms of reducing themselves to outrageous racial caricatures that, looking back with 2025 eyes, were embarrassing and degrading but that, at the time in the 1940s, were quite profitable and popular.

Anyway, the first mention in local Crescent City media of the Zulo Hippopotamus that I found was the June 20, 1942, edition of the New Orleans States newspaper, which reported that the new aggregation would be sponsored by the locally based Jackson Brewing Company, makers of once-popular but now gone Jax beer.

“The team will be called the Zulo Jax Hippopotamus and will be dressed in Carnival (or Mardi Gras) style,” the paper noted, adding that the club was still seeking a few more players.

The Zulos apparently were scheduled to make their debut July 4 in a road doubleheader against a team in Bogalusa, a town in Washington Parish about 65 miles north of New Orleans across Lake Pontchartrain.

However, I couldn’t find any record of those contests actually taking place, so it looks like the Hippopotamus were introduced to the world when they stepped onto Hi-Way Park in New Orleans to face the Ryan Stevedores, a local club composed mainly of Mississippi River dockworkers, called stevedores.

In the lead up to the clash between the Zulos and the Ryans, the July 11 issue of the States called the Hippos “[s]omething new in Negro baseball” and that they “will be dressed in black uniforms and grass skirts [and] will wear wigs and comedianlike [sic] faces.”

The paper listed the team’s lineup, in which the players used goofy, supposedly “African” aliases like Zupotamus, Zipanter, Hippo and Zulk.

The unit’s second baseman, Joe Wiley, was a local star who ended up being dubbed Bozo for the Zulos. It also appears that another well traveled regional favorite, Kildee Bowers, played right field under the alias “Big Chief” Kobo.

The earliest reference of the Zulo Hippopotamus I came across in The Louisiana Weekly newspaper is the publication’s July 18, 1942, when it reported on the “newly organized baseball team” and its 6-4 win over the Ryan Stevedores in the Zulos’ debut contest July 11. (A doubleheader was originally scheduled, but the second game was called because of darkness.)

“The Zulos[,] wearing black uniforms and kinky wigs and comedian like faces[,] have some of the best players in their city in their club, each bearing a nick name [sic],” the paper stated, noting that the Hippopotamus’ “Denzo” earned the W on the mound.

The newspaper added that the Zulos were already looking forward to further action on the diamond.

“For the benefit of baseball fans who did not get a chance to see the Zulos in action at Hi-Way Park last Sunday will have a chance to see them in action on July 19 at Hi-Way Park,” reported The Weekly. “This is to be one of the interesting [sic] games of the season, because the Ryans want revenge and the Zulos will try to keep them from getting that revenge and not break their start of a winning streak.”

The mastermind behind the creation and management of the Zulo Hippopotamus was Jacob White, a Mobile, Ala., native who worked as a longshoreman on the New Orleans docks. The team’s headquarters was 1200 S. Rampart St., which, according to various documents, was White’s residence, which placed them in the Central City neighborhood.

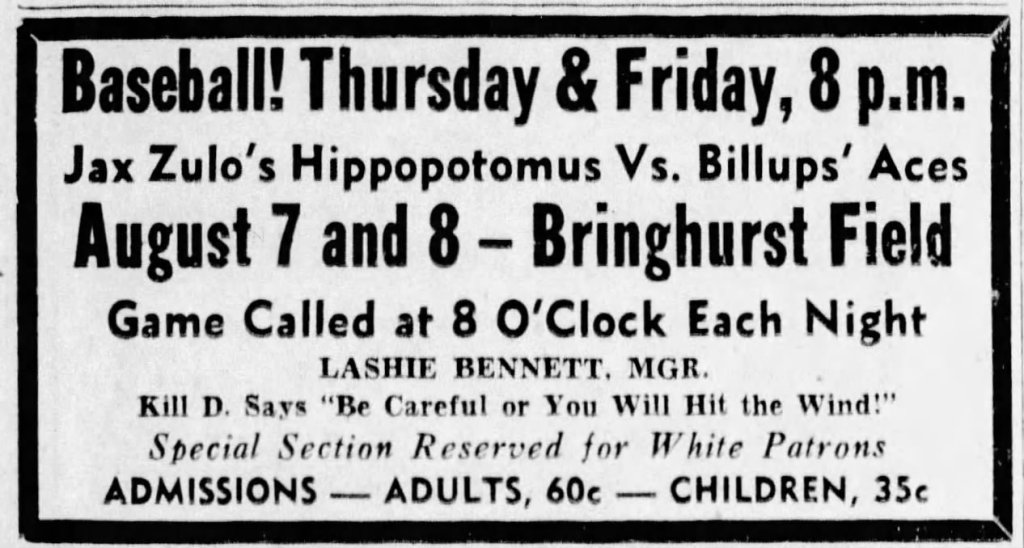

That’s the only reference I found to the Zulo Hippopotamus in The Weekly 1942, and in 1943, I couldn’t find any reference to the team until very late in the season – the end of October, to be precise. That’s when the Zulos squared off against the Jax Red Sox of Houma, La., a town about 60 miles to the southwest of New Orleans in Terrebonne Parish, for what The Weekly described as the “state championship” of Black baseball.

The Houma club was led by sawed-off half-pint pitcher Frank Thompson, nicknamed the Ground Hog because he was reportedly a squat 5-foot-2, with a cleft palate, a scar on his lip, and a broken, jagged bottom that protruded like an upside down tusk.

But Thompson’s unusual physical appearance belied his substantial talent on the mound; for the better part of the 1940s, the Hog was a frequently dominating pitcher in New Orleans and the entire region. He was so good that he spent four seasons in the big time, pitching for the Birmingham Black Barons of the Negro American League and the Homestead Grays of the Negro National League, compiling a cumulative record of 12-10 with a 3.51 ERA and an ERA+ of 113.

The Red Sox were for several years a formidable semi-pro team overall, too, and had posted a reported record of 23-2 in 1943 heading into the scheduled showdown with the Zulos.

But the Hippopotamus wasn’t just a collection of clownish stereotypes the Zulos boasted a virtual who’s who of New Orleans Negro League legends, beginning with the Skipper himself, Wesley Barrow, the greatest manager in New Orleans Black baseball history. In The Louisiana Weekly, Barrow was referred to as “Weslie Barral,” and his Zulo “name” was Big Chief Foozy. I am unfortunately not making that up.

The Zulo lineup was absolutely loaded. At shortstop was New Orleans native Billy Horne, who spent time in the top levels of Black hardball, primarily with the Chicago American Giants and the Cleveland Buckeyes. His Zulo character’s name was Zupater.

Patrolling left field was Gretna, La., native J.B. Spencer, who usually played in the infield, including with the dynastic Homestead Grays, the New York Black Yankees and the Birmingham Black Barons. Spencer received the Zulo moniker of Zulk.

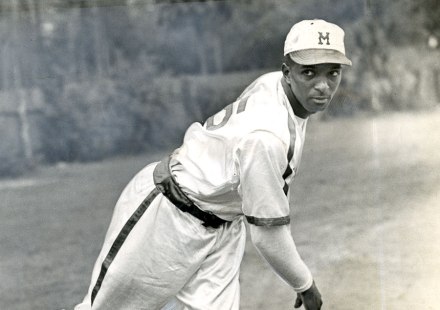

And, perhaps most significantly, the Hippos had pitcher John Wright, a New Orleanian who is most widely known as a staff ace for the 1940s Homestead Grays dynasty, and as the second African American signed to a Major League Baseball contract, following Jackie Robinson to the Brooklyn Dodgers organization. Zuba was Wright’s name with the Zulos.

According to The Weekly, the Zulos got a late start to the season but still managed to bring a record of 10-1 into the game with the Red Sox; the Hippopotamus, for example, had just beaten and tied the Gulfport, Miss., Black Tarpons.

(Interestingly, both teams in this “state championship” clash were sponsored by Jax Brewery, a less than surprising situation given that Jax sponsored many area baseball teams over the years, Black and white, pro and semi-pro.)

Between the star powered novelty of the Zulo Hippopotamus and the captivating character who was Frank “the Mighty Ground Hog” Thompson, the clash was a marketing goldmine for Allen Page, New Orleans promoter extraordinaire and successful entrepreneur, who booked the teams into Pelican Stadium for Oct. 24.

In the end, the Zulos proceeded to claim what was billed as the state championship for 1943 by beating the Houma club, 2-1, in the first of two scheduled games. Roughly 2,300 folks turned out the Pelican Stadium for the games and saw Wright go the distance on the mound for the Hippos and secure the win. Although the second game was called because of darkness, with Houma leading 9-3, The Weekly declared that Page and Zulos owner Jacob White “were convinced that the fans were satisfied at the way those boys performed.”

The Zulos then wrapped up their ’43 season with an 8-2 win over the Mobile, Ala., Black Shippers on Nov. 14 in another matchup arranged by Allen Page.

However, despite their success on the field and (apparently) at the gate, the deeply problematic nature of the Zulos’ clowning schtick and the way it pandered to ugly stereotypes of people of color didn’t win everyone over as fans. In the Nov. 20, 1943, edition of the Cleveland Call and Post, an unnamed sports columnist tore into the Hippos’ degrading conceit (warning about bizarre punctuation and text stylization):

“I notice that two of ‘our’ teams will play a baseball game in New Orleans Sunday afternoon. … They are the MOBILE BLACK SHIPPERS and the (hold your breath, please!) – JAX ZULU [sic] HIPPOPOTAMUS — (you may relax now.) Yep! Those are the names of the teams. And I thought ‘Ethiopian Clowns’ was bad enough.

“Do You ever stop to wonder why Negro teams have to adopt such unearthly names? Maybe it helps their playing ability???? It also ‘helps’ our reputation as a race of clowns.”

It’s a blistering critique of a team – and the idea of pandering to the lowest common denominator – that now, eight decades later, seems not just offensive, but actually culturally regressive.

(News of the Zulos’ existence and gimmick reached the mainstream media in other parts of the country as well, including the Associated Press, one of whose columnist, Romney Wheeler, found the novelty team somewhat amusing. “And a bright note for baseball: the Zulu Hippos, and newly formed negro [sic] team, left New Orleans for its first game dressed in mardi gras [sic] costume – the first time this season any club has felt the need of rejoicing clothes,” Wheeler penned in July 1942.)

The 1944 season involved a handful of Zulo games, includingh a season-opening road loss to the Black Shippers in Mobile; a 0-0 tie with the Gulfport Black Tarpons in Pascagula, Miss.; several more games against the Houma Red Sox; a 7-0 whitewashing of the Regal Cubs in Lodbell, La., a contest that drew about 1,200 spectators; a one-run triumph over the Port Gibson (Miss.) Adds; a defeat in Slidell, La., at the hands of the Jax Red Sox of New Orleans (this Jax team appears to be a different one from the aforementioned, Ground Hog-guided Houma Jax Red Sox); and a 6-4 victory over the Houston Tigers.

The most significant development of the 1944 Zulos campaign came in May, when Robert “Big Catch” Carter, a popular, well regarded local outfielder and manager whose most respected tmanagerial stint (or at least the one I know the most about) was with the Metairie Pelicans, a top-quality semi-pro baseball club based in the small city just to the west of New Orleans.

According to the May 20, 1944, Louisiana Weekly, Carter more or less volunteered to take over the piloting reins of the Zulo after watching the Hippopotamus lose to the Houma Red Sox, 20-4, at Pelican Stadium in a rare mound loss for Ground Hog Thompson.

The newspaper opined that with Carter, the Hippos could look forward to a markedly brighter future.

“The Zulos played a good game of baseball, and the fans in Houma were well pleased with the airtight game,” the publication stated. “The Zulos are in much better shape than they were when they met the Red Sox at Pelican Stadium May 7 and lost the game, 20-4.”

The newspaper said that Carter “watched the game [and] … immediately offered his services to strrengthen the club. … [and] has already added some new players to the team, and from the way he feels about the matter he only needs a shortstop, then the fans of New Orleans will have a team to be proud of.”

The ensuing seasons for the Zulo Hippopotamus baseball team (I was able to look through The Louisiana Weekly archives up through 1947) unfolded in much the same manner as the first couple years of the club’s existence – mostly road games across Louisiana and into Mississippi, including games in Lake Charles, Alexandria, Rosedale, Shreveport and White Castle, La.; and Jackson and Hattiesburg, Miss.

Exactly how long the Zulo Hippopotamus lasted as a coherent group of athletres is unclear; like I previously noted, I only went through old newspaper archives up through 1947, and given that Negro Leagues records and statistics were always spotty at best, and that by the 1960s or 1970s, we might not be able to readily find out the length of life possessed by the Zulos.

What is known, though, is that a lot of players came through these two talent pipelines – and although many of the details are either a complete mystery or ride, the tale of the New Orleans Zulo Hippopotamus, a weird little baseball team that dreamed big and made its complicated, weird mark on a city that itself is just a little weird and an awful lot complicated.