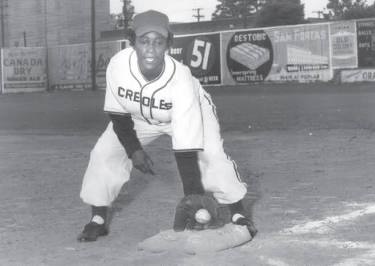

In January 1947, The Louisiana Weekly newspaper in New Orleans announced that Allen Page, a longtime sports promoter, baseball impresario, hotelier and businessman, was busy forming a new hardball team for African-Americans in the Big Easy. Dubbed the Creoles, the new organization was slated to start spring training in late March, and, reported The Weekly, “Page … is now signing up ball players” and “inviting all young baseball players … to contact him at the Page Hotel, 1038 Dryades St. …” The article also noted that the team’s home field would be at Pelican Stadium.

Two months later came the arrival of the Creoles’ first manager – 41-year-old Harry Williams, a respected, longtime Negro Leaguer who started his career in the top levels of Black baseball in the early 1930s and for 15 years or so hopped around to several clubs. He got into managing circa 1943, serving piloting tenures with, most recently, the Baltimore Elite Giants and New York Black Yankees.

The 1947 New Orleans Creoles’ season began, anchored by Allen Page, whose long-term impact on the National Pastime, both in NOLA and through the whole Black ball world, has been immense, as his son, Rodney Page, wrote a few years ago in a short article/tribute to Allen.

“The true story of Allen Page is his indomitable spirit, which speaks to the heart of self-reliance, self-definition, and self-determination,” Rodney wrote. “He transcended and excelled despite the shackles of the Jim Crow South and overt racism in America. A legacy of firsts was in his DNA.”

As alluded to the introduction to this post, one of Allen Page’s boldest, most daring moves as an owner and operator during his several decades in New Orleans previously owning and running several franchises earlier in his career, such as the Black Pelicans and Crescent Stars, was the launching of a fairly successful Negro minor league team just as integration had started the process of teams in Organized Baseball poaching the top talent from the Black circuits.

According to contemporaneous media coverage – particularly in The Louisiana Weekly – the New Orleans Creoles of the late 1940s were reliable members of the Negro Southern League who fared pretty well on the diamond, in the stands and out among the public.

The Creoles also reportedly maintained a working relationship with the Negro National and Negro American leagues, which makes sense, given the NSL’s ox thinking was the inclusion of women in the Creoles’ lineups, the highest-profile of which was doubtlessly Toni Stone, an infielder (usually second base, specifically) who starred for the Creoles in 1949 and later for the Negro American League’s Indianapolis Clowns.

Stone wasn’t the only woman to grace the rosters of the late-1940s New Orleans Creoles; in 1948, for example, Page brought aboard outfielders Fabiola Wilson, a former student-athlete at Xavier University of Louisiana in New Orleans, and Gloria Dymond, from Southern University in Baton Rouge. All of that was several years after Georgia Williams pitched for the Creoles in 1945.

There was one more female New Orleans Creole in the late 1940s, but we’ll save her for our next post about the club.

In addition, obviously 1947 was a pivotal year in the history of baseball in the United States (and eventually in many other parts of the world in general. It was the year Jackie Robinson broke Major League Baseball’s egregious color line with the Brooklyn Dodgers, which naturally served as part of the backdrop for Page’s and the Creoles’ exploits.

For simplification purposes, this post will largely focus on the New Orleans Creoles’ 1947 season, their first in existence under Allen, so we’ll now return to the narrative begun at the start of this post …

I’m going to try very hard not to get bogged down in too many specifics about the ’47 Creoles and just zero in on a few developments and trends that highlighted the season for the New Orleans crew.

In terms of significant developments or occurrences, there were two I want to point out. The first came in late April, when Page managed to wrangle in five players from the stellar Cuban professional league, including catcher Francisco “Frank” Casanova and pitcher Wenceslao Gonzales, the latter of whom I’ll examine in a little more depth in my next post about the 1947 Creoles.

“In an attempt to place a team in the Negro Southern League that is worth[y] of the great sport loving city that is New Orleans,” stated the April 26, 1947, issue of The Louisiana Weekly newspaper, “Allen Page, owner of the local league entry, has the services of five outstanding players” from Cuba.

The newspaper noted that the signing of the five Cuban ringers was facilitated by Alex Pompez, the owner of the Negro National League’s New York Cubans team. Pompez, a National Baseball Hall of Fame inductee, was close friends with Page and visited New Orleans frequently. The Weekly also stated that, essentially, the Creoles were a farm team for the NNL squad.

The inking of the five Cubans underscored the diverse locales from which Page plucked the members of the ’47 Creoles, reported the newspaper, which added, however, that the team’s roster was also stocked by much local talent, too.

“Although first preference for berths was given to local boys,” the paper said, “the lack of proper response and the refusal of candidates to report [to the team] consistently have forced … Williams to bring in many of the players who have written in from all over the country. However, despite the fact that players from Indiana, Illinois, Pennsylvania, Alabama and Ohio have been grabbed the spotlight [sic], at least six Louisiana youths, including four New Orleans lads, have showed [sic] enough to warrant at least four starting berths.”

The second major development in the Creoles’ season took place occurred on an executive level. Upon the death of then-NSL president Tom Wilson in late May 1947, Page was selected to succeed the revered Wilson, who had been a team owner and league executive in multiple Negro professional loops for nearly 30 years.

In covering the NSL’s season organizing meeting in Nashville (the home of the league-member Cubs) in late May, newswire reporter C.J. Kincaide noted the election of Page as league president.

“Mr. Page is no new figure to baseball,” Kincaide wrote. “In addition to being a successful businessman in New Orleans, he has been a promoter of baseball for a number of years and is well-known and highly respected by owners and managers of both the Negro American and National Leagues.”

In his article, Kincaide quoted Page himself, who told the reporter that “we have a big job to do, if for no other reason than for Tom Wilson who all baseball men loved and respected.”

While it was certainly an honor – and an assumption of significant responsibility – for Page to be elevated to the head of a far-reaching organization, he had assumed similar league executive positions before, and he would later, a fact that reflected how respected and capable he was for shepherding numerous teams into a functioning operation spread out of several states at a time in history when the long overdue integration of Organized Baseball was starting to gradually chip away at the viability of Black baseball.

Pundits from around the country chimed in with their thoughts of and hopes from Page’s ascension to league president, and what it might mean for the NSL. Referring to the building of a new edition of the NSL, seasoned journalist and columnist for the Pittsburgh Courier Lucuis Jones wrote that Page was tasked with “[b]ringing the Southern League in its own [as] a two-year overhauling job.” He added that Page was an excellent choice to succeed Wilson, calling Page a “nationally-known team owner and sportsman,” and the scribe reported that Page thought that “a powerful … six-club circuit in which all the clubs are within a 500-mile radius of each other is a better financial proposition … and much more [stable] than an eight-club league” in which some teams must travel more than 500 miles and possibly barnstorm on the way in order to play every other league team.

Jones further outlined Page’s thoughts about the future of the NSL, noting that the new president said the league’s players must be aware of the importance of putting quality teams and exciting play when they take the field.

Every club cannot have a winning outfit. But every team can hustle and display sterling sportsmanship.

Allen Page, stated to columnist Lucius Jones

Jones penned that Page “stated firmly that effective at once, every club must require its players to hustle throughout every game and cease their ‘umpiring.’ Failure to adhere to these directives may bring fines or suspensions or both. ‘Every club cannot have a winning outfit,’ said Mr. Page … ‘But every team can hustle and display sterling sportsmanship.’ This will win the public anywhere, any time, [sic] it’s good box office and it’s a fool-proof way to get the cash customers …” to come to games.

Aside from these two events – the Creoles’ recruitment of Cuban players to beef up the team’s roster, and Allen Page becoming league president – the 1947 Creoles season marked a trend followed by Page and his teams over the course of several years.

Namely, that Page brought aboard women to his baseball operations, either as coaches or players, making him, and the women he signed for his teams, early trailblazers in women’s sports.

Although previous baseball history featured a bunch of women’s teams, both Black and white, that had played, often by barnstorming, America’s pastime – and, especially, the famed All-American Girls Professional Baseball League during World War II – Page was one of the very first baseball figures to sign individual women to his otherwise male teams.

That was especially true of his New Orleans Creoles teams of the late 1940s. The most famous woman recruit, of course, was Toni Stone, an infielder who suited up for the 1949 Creoles before moving on to the Black baseball big time with the Indianapolis Clowns.

In addition to Stone, New Orleans native and former Xavier University of Louisiana student Fabiola Wilson and Gloria Dymond, who had attended Southern University, to take the field for the Creoles in ’48.

However, there was another women plucked from the ranks to play for the Creoles – former UCLA student-athlete Lucille Herbert – sometimes referenced by her married name, Lucille Bland – to act as one of the team’s on-field base coaches in 1947, a move that caught the attention of local fans and national journalists. I’ll discuss Herbert in more depth in an ensuing post.

On top of these factors, like countless other Black baseball teams at that time, the Creoles did their fair share of barnstorming across the country, and in 1947, the Crescent City club took several weeks in July to head north and east to take on various diverse aggregations on the way.

After a bus breakdown in Delaware and a few game cancellations and rescheduling, the Creoles played semipro teams in several Northeast states and locales, including Union City, N.J.; eastern Pennsylvania; Wilmington, Dela., where they played the similarly barnstorming Cincinnati Clowns; and in New York City, where they lost a pair of games to the famed Bushwicks of Brooklyn and crossed bats with their NSL rivals, the Asheville (N.C.) Blues as part of a doubleheader at the Polo Grounds. (Unfortunately, the Creoles did a figurative face-plant on the big stage, losing to the rival Blues, 15-2 in front of 9,000 spectators. The second game of the doubleheader was a showdown between the NNL’s New York Cubans and New York Black Yankees, with the Cubans winning the contest.)

The Creoles trekked back to the Crescent City in time for a home series with the NSL Nashville Cubs beginning July 13, but not before stopping in the City of Brotherly Love for a tilt with the Negro National League’s Philadelphia Stars. That clash ended in the 12th inning with the score knotted at 5-5; the teams ran up against the city’s midnight curfew, forcing the game to be called and left unsettled. The highlight of the affair was a grand slam by Creoles right fielder Fred McDaniels.

Other road trips made up a further significant amount of the Creoles’ schedule, including early-season warm-up exhibitions in McComb, Miss., against a squad from Hammond, La.; a conflagration against the Cinderella Sports in Monroe, La.; a trip to Grambling, La., to square off against the Grambling State University team; contests at various spots in the Pelican State against fellow Louisianian teams from Lake Charles and Shreveport; and showdown in Selma, Ala., against a team from that city.

Even many official NSL league games were held on the road in neutral locations. When the Creoles ventured to North Carolina during the last week of May to face fellow NSLers the Raleigh Tigers, games weren’t just played in Raleigh proper. The teams also faced off in Clinton and Goldsboro. And the Creoles crossed bats with league powerhouse Asheville at different cities and towns in the Tar Heel State.

The Creoles also ventured into the Lone Star State a couple times to play both Texas squads and NSL rivals at neutral sites. In mid-June, for example, they made their way north and west, first to play another of their NSL foes, the Atlanta Black Crackers, in Shreveport, La. They beat the Black Crax 8-7 in front of more than 3,000 fans, then headed to Longview, Texas, where they were scheduled for another game with the Crackers.

As with other teams Negro League teams, the 1947 Creoles at times traveled with an NSL rival, the Atlanta Black Crackers and the always-league-leading Asheville Blues, a situation the Creoles employed when venturing to east Texas via games at Shreveport or Little Rock, Ark.

The Creoles returned to northeast Texas in late June-early July, to, among other tasks, take the field against league opponents the Chattenooga Choo Choos, as well as an East Texas all-star team comprised of players picked from various semipro clubs in Texas, particularly in the eastern side of the state. The Creoles beat the picked nine, 7-3.

It also must be noted that I couldn’t find the results of several Creoles games as previewed in newspapers across the South – such as apparently scheduled contests in Macon, Ga., in June; Hickory, N.C., also in June; Longview; and elsewhere. But again, such willy-nilly plans and scheduling often never worked out in the Negro Leagues, and teams picked up games – both in-league and barnstorming or exhibitions – whenever and wherever they could.

Hence, when accumulated into a whole baseball season, all of these highlights sort of reflect the colorfulness, unpredictability, resourcefulness and adaptability that were so common with pre-integration African-American baseball.

The Creoles and their owner, Allen Page, employed creativity when battling the uncertainty and roadblocks that constantly popped up for teams in at all levels of the Negro Leagues. In that way, they were very much a typical Black baseball enterprise, especially those that took place in the late 1940s and into the ’50s, when integration was gradually but steadily eroding the Negro Leagues’ cultural importance and fiscal bottom lines.

Sprinkled throughout the Creoles’ season were a handful of other events, including a charity game in late June against a collection of all stars from other local clubs at Pelican Stadium. Benefitting the New Orleans Mardi Gras Association, the contest pitted the Creoles against a squad composed of players from the New Orleans Black Pelicans, Dr. Nut Tigers, Algiers Giants, Regal Tigers, Kenner White Sox and other aggregations.

The all-star roster was led by catcher Lionel Decuir, who played several seasons in the Negro League big-time with the Kansas City Monarchs and others, and the one and only Robert “Black Diamond” Pipkins, a well traveled, highly sought after baseball mercenary of sorts who, like Decuir, broke into the Black majors, specically with the Birmingham Black Barons.

The benefit game ended with the Creoles’ 14-3 drubbing of the all stars, with the highlight being an inside-the-park home run by the Creoles’ Oliver Andry, a stubby but fiery team sparkplug whom I’ll examine, like Herbert and Gonzales, in an ensuing installment. The day featured other events, including a youth baseball clinic by Manager Williams for about 260 youngsters.

With all that said, how did the New Orleans Creoles do on the diamond and at the gate? How good were they in action and attendance?

Well, it’s a little hard to say. We’ll look at that in the next post on the Creoles.