Before I complete the tale of the 1947 New Orleans Creoles (first two installments here and here), there’s a few other cool things I want to get to, including today’s post.

For this piece, I’m going to jump way back to something I discussed and wrote about in fall 2014 – that’s right, more than a decade ago. Here’s my article in the Philadelphia Inquirer, and this and this are the blog posts I wrote.

At that time, I somehow learned about (I can’t recall how, exactly) Alexander Albritton, a pitcher whose career in the upper echelons of Black baseball was mainly during the 1920s. I wouldn’t necessarily call his career brief, but it was generally unremarkable. He seems to have been a decent flinger of the horsehide, but he was far from a Hall of Famer. He could have brilliant outings, but he got just easily got shelled.

But his quality as a pitcher doesn’t really figure into the main thrust of his story.

What Albritton is most remembered for – the thing that makes his life truly remarkable – is his tragic death at the age of 45.

That death came in February 1940 while he was a patient at Philadelphia State Hospital, a notoriously decrepit, filthy and horrific public psychiatric facility commonly known as Byberry Hospital.

Albritton died at the hands of Frank Weinand, an orderly at the hospital who beat poor Alexander to death, allegedly to subdue Albritton during a psychological breakdown.

In addition to Byberry’s troubled, corrupt existence during its time – it finally closed in 1990 after numerous investigations into the deplorable conditions and questionable methods of its staff – several questions and mysteries remained, such as where exactly he was buried (I was unable to confirm his final resting place back in 2014).

But the biggest blank space in Albritton’s saga was what precisely caused his death. News reports at the time weren’t able to offer any clarity, mainly because on Albritton’s death certificate, the lines for the principal cause of death just stated “inquest pending.”

So it was apparently unknown, or at least unverified, exactly what Weinand did in his physical altercation with Alexander that killed the latter on Feb. 3, 1942.

Since I wrote the article on Albritton for the Philadelphia Inquirerer and the corresponding posts I penned on the sad incident, I hadn’t really revisted the Alexander Albritton tale for many years.

But a couple weeks ago, something made me circle back to the tragedy just to see if anything new had developed or emerged since 2014. I’m not sure what prompted me to check it out; it just kind of struck me one day. I had a feeling.

Turns out it was a good thing, too, because I did indeed find something new.

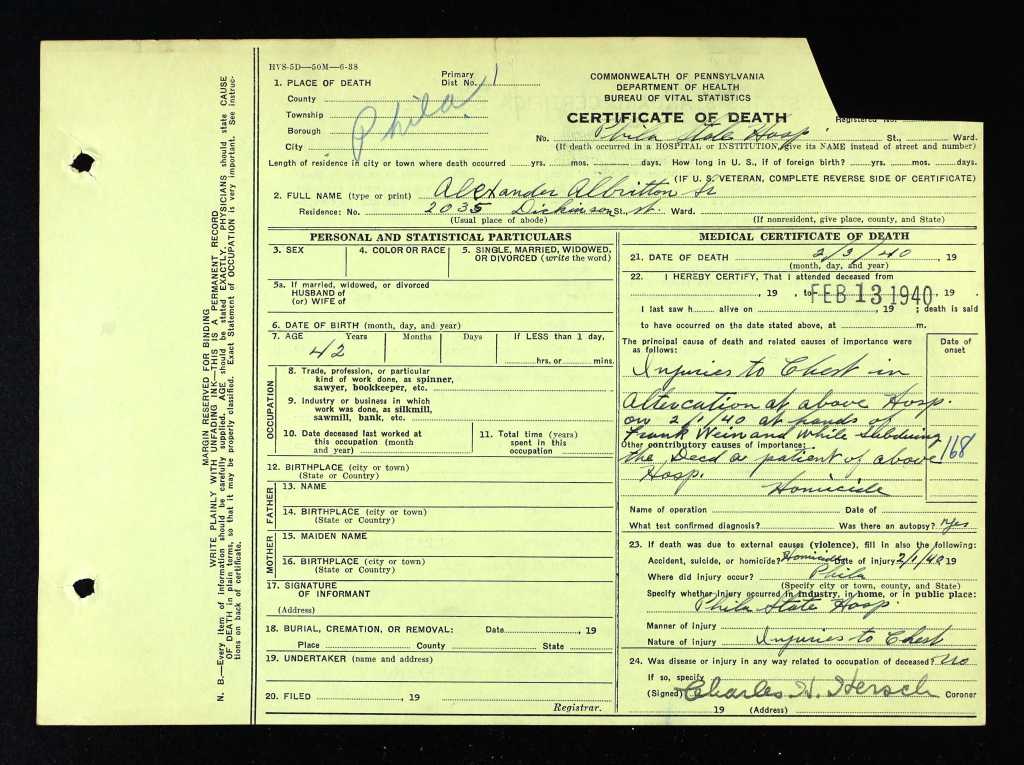

Namely, a second death certificate! One that included the actual results of the inquest/autopsy of Albritton’s body!

When I did take a return dive into the story a couple weeks ago, I hopped on Ancestry and did a search or two on Albritton’s life, including looking up the death certificate for the heck of it.

At first, what I found was the same document I came across in 2014 – with the same old “inquest pending” rubber stamp on it.

Curious as to whether there might be any addendums or anything attached to the primary certificate page, I clicked to see the next page of records that had been uploaded to Ancestry.

Lo and behold, there was now a second death certificate following the original, and it was one that had filled in the lines for the exact cause of death.

I don’t know precisely why I hadn’t uncovered the follow-up certificate 11 years ago, i.e. whether I was sloppy or careless in my reporting or if the additional document had been filed and uploaded since 2014.

Regardless of how it happened, it happened, and now, with a decade of additional lessons learned about journalistic investigation and historical research, I’d found something big.

So what caused Alexander Albritton’s death? States the newfound document: “Injuries to chest in altercation at above hosp. [sic] on 2/1/40 at hands of Frank Weinand while subduing the decd [deceased][,] a patient at above hosp. [sic].”

The ruling of the coroner, Charles H. Hersch: “Homicide.”

Murder was the case, indeed.

Now, as reported by the contemporaneous media of the time, Weinand was charged with murder on Feb. 5, 1940, but eventually he was largely cleared of wrongdoing by the investigation into Albritton’s death; the post-incident probe determined that Weinand had acted in self-defense when Albritton allegedly attacked the orderly with a broomstick. (The charges appear to have been downgraded at some point to manslaughter.)

However, even with the completed autopsy results, the second death certificate leaves a lot of curiosities and questions about what all happened. There’s also a lot of details about the case that, whether due to unavailability of information or lack of time on my part, I wasn’t able to fully explore and write about over a decade ago.

First, there’s other differences between the two death certificates. The most noticeable is that the spaces for background information about Albritton, or any deceased person – sex, race, relatives, spouses, addresses, birthday and place, etc. – are filled out on the initial document but left largely blank in the second one, probably because it would have been roughly the same information.

Another key difference between the two versions is the listed date of death; on the first one, it’s stated as Feb. 3, 1940, but on the ensuing one, it’s Feb. 1, 1940.

The variation can most likely be attributed to the gradual discovery and revelation of the complete and accurate account of what had taken place between Albritton and Weinand. In the particular case of date of death, it eventually came out that Albritton’s body – indeed, the fact that he was dead – wasn’t discovered for a couple days by hospital staff.

What seems to have happened is that Albritton’s body was likely found on Feb. 3, at which time staff and investigators probably just assumed that he had died that same day, but subsequent multiple investigations by the State Police, the Philly police and others found that the altercation between Albritton and Weinand actually occurred two days earlier.

It then took staff, doctors and others to not even realize for two days that Albritton was dead and hadn’t been treated at all for the injuries – which included, it seems, four broken ribs, a punctured lung, and constusions to the torso and arms – sustained by the altercation. It would seem that whatever Weinand did to Alexander, it was severe, even with the former’s exoneration.

Another aberration between the two death certificates is the date they were filled. The first one indicates that it was logged on Feb. 6, 1940, but, curiously, there is no filing date on the updated document version, only that Hersch had “attended the deceased” on Feb. 13.

Yet another discrepancy is Hersch’s signatures – they look substantially different.

Moreover is the uncertainty about where Albritton’s body ended up. The initial death certificate states that the dispensation of the body took place on Feb. 9, 1940, at Eden Memorial Park cemetery of Collingdale, Pa. However, back in 2014 I called Eden to confirm, and the staff there said they had no such record of Albritton. (I also called three other possible cemeteries, none of which had any record of him, either.) Then, in the second edition of the death certificate, all of that information is left blank.

The details of the fatal incident are intriguing, and hopefully I’ll be able to talk about those at some point. I also hope to follow up on where Alexander was buried, as well as examine his family background.

But next up will eventually be a look at Alexander’s career on the diamond.

Pingback: Alex Albritton on the field | The Negro Leagues Up Close

Pingback: The Negro Leagues Up Close

Pingback: Tragedy, nomadic life in the Albritton family | The Negro Leagues Up Close