Editor’s note: This is the third and final installment of a series about the 1947 New Orleans Creoles. The previous parts are here and here.

I’ll launch this concluding chapter by concluding the story of the official 1947 Negro Southern League season. Like many a season in Black baseball, the ’47 NSL campaign was one filled with uncertainty, irregularity and seat-of-one’s-pants planning.

Schedules were always adjustable, including official league contests, and at the mercy of financial realities, travel complications and other variables that were always shifting throughout the season.

So by what was declared the end of the regular season, it was unclear about what to do in determining a league champion. From what I can glean, everyone involved agreed that the powerhouse Asheville Blues had won the first-half championship, but there was less consensus about who won the second half.

At one glance it appeared the Blues had nabbed the second-half flag as well, which would have automatically made them league champs. However, the New Orleans media announced, somewhat unilaterally, that the Creoles had won the second half, thereby setting up a playoff between Asheville and New Orleans.

For whatever reason, all agreed just to hold a best-of-five championship series between the Blues and the Creoles, which began Sept. 12 in New Orleans.

“HEAR YE! HEAR YE! COME ONE, COME ALL,” wrote The Louisiana Weekly’s ace scribe, Jim Hall, in the paper’s Sept. 6 issue.

“Haven’t you heard the latest news? There is going to be a town meeting at the Pelican Stadium,” Hall added.

He continued later in his article: “Now, that you have the news, the old town-crier will stop singing the blues. But I must make this last call. Hear Ye! Hear Ye! COME ONE! COME ALL!”

The teams split the opening two games, both held at Pelican Stadium, then the New Orleans guys took game three, 4-1, at Baton Rouge.

However, the Blues rebounded with a 10-5 win at Shreveport to even the series at two games each, and they clinched the series and the NSL championship with a dominant 16-4 triumph in game five in Beaumont, Texas.

Thus ended the 1947 Negro Southern League season, with the New Orleans Creoles as runners up. The Creoles tied a bow on a relatively successful debut campaign by beating the visiting Indianapolis Clowns, 11-8, in an exhibition at Pelican Stadium on Oct. 2. Page somehow got Negro Leagues big-timer Chet Brewer (Cleveland Buckeyes) in pitch in the game against the Clowns, with Baton Rouge native Pepper Bassett, aka the Rocking Chair Catcher, backstopping.

William Plott, in his comprehensive book history of the Negro Southern League, described the life in the NSL for teams like the Creoles. In particular, he explained what the league meant for players.

“The Negro Southern League gave a home to professional baseball in Southern cities that could not field teams at the Negro National League level,” Plott wrote. “… In those cities were players whose renown would hardly leave their expanded neighborhoods. Thousands of them played the game in even greater obscurity than did their counterparts in the ‘major league’ Negro National League and later Negro American League. The Negro Southern League was minor league baseball … That means that the number of players who went on to become major leaguers … was relatively small.”

Plott added that the achievements, both routine and extraordinary, of the NSL’s players were quite often obscured, clouded, forgotten or ignored, the result of spotty media coverage, poor record keeping – Plott noted that “[n]o official statistics were ever issued by the league” – and irregular scheduling.

It was in this stark reality that the following three 1947 New Orleans Creoles toiled with a universal zeal for the national pastime.

Wenceslao Gonzales O’Reilly – In April 1947, Creoles owner Allen Page turned to a close friend to boost the Big Easy team’s roster, a move that brought five ringers from the storied Cuban Professional League. The personnel coup was arranged by Alex Pompez, the owner of the New York Cubans of the Negro National League and one of Page’s dearest friends. (Pompez was eventually ushered into Cooperstown in 2006.)

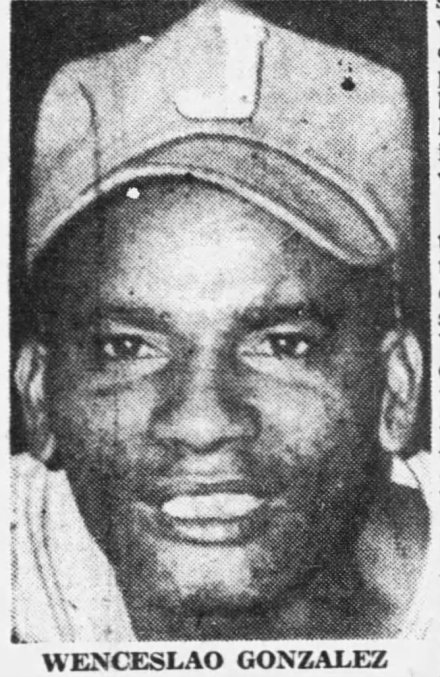

Among that group of five hired guns was pitcher Wenceslao Gonzales, a fresh-faced native of Quivican, Cuba, who was five months away from his 22nd birthday when he arrived in New Orleans.

Gonzales’ primary “claim to fame” was a single Major League Baseball appearance, with the Washington Senators on April 13, 1955, eight years after becoming one of the staff aces for the modest New Orleans Creoles.

Here’s how the Tucson (Ariz.) Citizen newspaper described Gonzales in June 1953, while he was playing minor-league ball with Cuidad Juarez (located in the Chihuahua state of Mexico) in the Arizona-Texas League:

“By stretching the imagination a trifle, we find that Wenceslao Gonzalez [sic] of Juarez … is a left-handed version of the famous Satchel Paige,” wrote the Citizen’s Ray McNally.

“Like Paige,” McNally added, “Gonzalez [sic] is “a pitcher with oodles of stuff, a variety of deliveries, [and] a sensational mound record. He’s a fellow whose age offers an interesting point of speculation and a guy who has plenty of color.”

The Citizen further analyzed Gonzales’ strengths as a pitcher, asserting that the Cuban southpaw “appears to have a rubber arm – one of those valuable pieces of a pitcher’s armor that seems to get better with age.”

But back in 1947, when he signed on with the New Orleans Creoles, he was barely in his 20s and fresh from a tour of duty in the Cuban Navy during World War II, ready to start his professional career. He’d spent eight years in amateur beisbol in Cuba, including an early stint on the Cuban national team in 1939 at the age of 14, when the club won the Amateur World Series, the country’s and the national team’s first international championship.

With the Creoles in 1947, Gonzales was generally viewed as the team’s pitching ace, something Pittsburgh Courier correspondent/columnist Lucius Jones asserted in a May 1947 column; Jones noted that Gonzales’ recent Creoles debut was a two-hit gem against the Memphis Red Sox.

Another article in the May 24 issue expounded on that notion: “Gonzales came to the states [sic] with high praise and in his only out[ing] he displayed a coolness and polish of a veteran and a rare assortment of every pitch in the book. He is destined to reach the highest rung in baseball.”

In its June 8, 1947, edition, the Chattanooga Daily Times asserted that “[t]he Creole pitching staff is built around” Gonzales, who “is the strike-out wizard of the Creoles and is leading the league in that department.”

Wenceslao Gonzales retired from professional baseball at the age of 43 and passed away a dozen years later at the age of 55 in Cuidad del Carmen in Mexico.

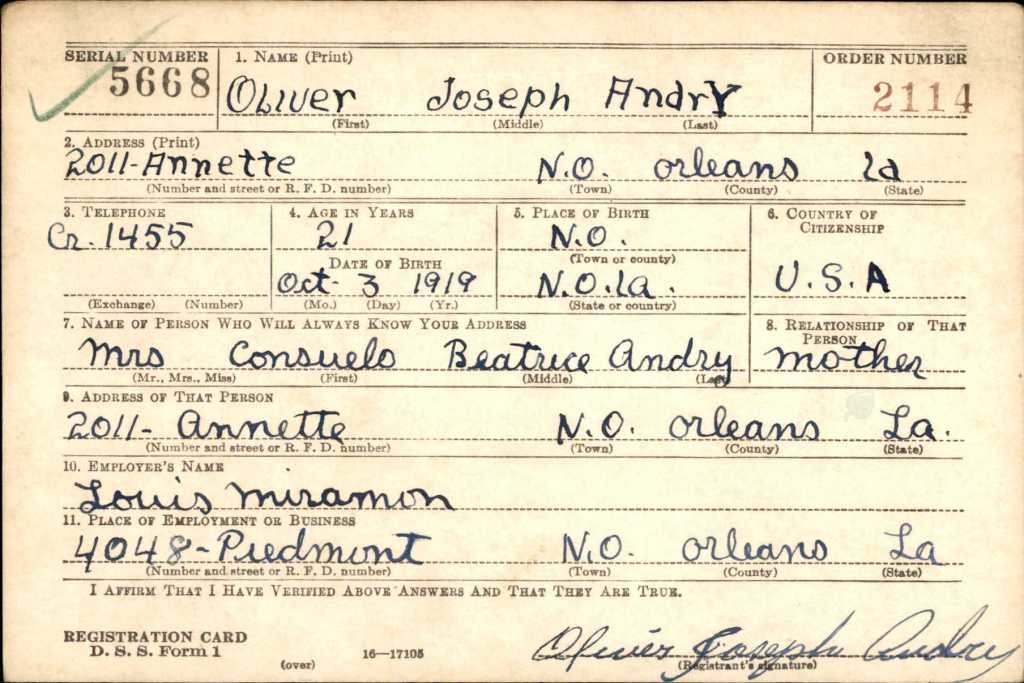

Oliver “Butsy” Andry – Oliver Andry was born on Oct. 3, 1919, in New Orleans; his parents were Willie Andry, a laborer for a steamship company, and Consuelo Andry, nee Jackson. When Oliver was a youth, the family lived on St. Anthony Street; later on, the Andrys moved to Annette Street in the same neighborhood.

Oliver was the third of (by my count) a dozen children and grew up in the historic Claiborne Avenue neighborhood, which, before it was chopped in half by the construction of I-10, was one of the liveliest, most tradition-rich Black sections of New Orleans.

By the time Oliver was in his early 20s, he was playing centerfield for the Dr. Nut Tigers, a New Orleans semipro team sponsored by the World Bottling Corp., a local company that produced Dr. Nut soda. In July 1941, Andry racked up two doubles and a homer in a Tigers game against a team from Houma. By trade he worked as a plasterer in building construction for Louis Miramon, a property developer from Slidell, La.

But in May ’42, Andry enlisted in the Army as a private and served his country for three-plus years in World War II. After being discharged in October 1945, Oliver – nicknamed “Butsy” – continued a career in semi-pro baseball that included a stint with Allen Page’s New Orleans Creoles.

He returned to the diamond in 1946, once again playing for the Dr. Nut Tigers.

Andry was a potent little sparkplug on the field. At just 5-foot-1 and a mere 125 pounds, Butsy flitted around the outfielder catching fly balls, but at the plate he boasted a surprising amount of power and prowess.

When he climbed aboard to New Orleans Creoles’ train, by mid-season 1947, Andry had turned into a fan- and media-favorite standout, both at home and on the road. In late May of that year, the Macon (Ga.) News stated that “[a]nother star with the Creoles who are expected to take a bright spot will be Oliver Andrews [sic], amazing outfielder”; a Louisiana Weekly cover of a doubleheader bringing the Atlanta Black Crackers to the Big Easy reported that “center fielder Oliver Andry performed miracle catches in the field and continually brought the crowd to its feet.”

Later in the season, the Atlanta Daily World, in its preview of a Creoles-Black Crax series, dubbed Andry “the dapper youngster who made several spectacular catches in centerfield.” In June, Andry hit a three-run, inside-the-park homer in the second inning in the Creoles’ 14-3 cakewalk over a composite local all-star team in an exhibition clash, prompting the Delaware County Daily Times of Chester, Pa., to write that Andry was “the best flyhawk in the state, is hitting well over .300, and is a speed merchant on the bases.”

Andry continued with the Creoles the following season, and his local renown continued to grow, with some media reports referring to him as unusually little – in August 1948, as the Creoles were prepping for a game against the barnstorming Cincinnati Crescents in Selma, Ala., the Selma Times-Journal stressed Andry’s tiny stature in a preview article, referring to him as “Oliver Andry, New Orleans boy, sensational midget leftfielder.

“When fans see Andry they will see a real Creole boy making some sensational catches in the left field garden. He is the fastest man on the team.”

Unfortunately, I couldn’t find any mention of Oliver in The Weekly over the next two seasons (1949 and ’50), so I stopped looking at that point.

As Oliver approached middle age, he attended Beecher Congregational Church in New Orleans, serving as a deacon, and by the 1950s, multiple generations of pretty much the entire Andry family lived on Pauger Street, still in the historic Claiborne Avenue district.

But later in life, Oliver Andry and his wife, Mildred (nee Sayas) Andry, whom he married in 1959, moved to Slidell, maybe 35 miles away from New Orleans on the northeast shore of Lake Pontchartrain.

Andry also took part in the Old Timers’ Baseball Club, a local organization of dozens of former Negro League and Black baseball players and managers; he sometimes played in the club’s annual all-star reunion game.

Butsy Andry died on Aug. 31, 2004, roughly a month before his 85th birthday, and was buried in Resthaven Memorial Park in the New Orleans East part of the city.

Lucille Herbert – “Miss Lucille Hebert [sic], former softball and [field] hockey star in California and one of the best feminine athletes in these parts, will be a regular figure in the frist[sic] base coaching box for the New Orleans ‘Creoles’ of the Negro Southern League this year. This wil make her probably the first woman in colored baseball history to be so intimately connected with the ‘playing’ end of a professional diamond aggregation.”

That’s how The Louisiana Weekly announced that Lucille Herbert, a New Orleans native and recent graduate of the University of California-Los Angeles, had been hired by Allen Page to blaze a trail in New Orleans baseball history.

While Page and the Creoles are well known as the folks who in 1949 famously hired the legendary Toni Stone, one of Negro League baseball’s earliest and most popular female trailblazers,

But Page plucked other women to join the Creoles’ roster and join his team, including Fabiola Wilson and Gloria Dymond. But Lucille Herbert (married name Lucille Bland) was the first, in 1947.

For her excellent book, “Curveball: The Remarkable Story of Toni Stone,” Martha Ackmann interviewed Lucille Bland, who told the author that Page ran an ad in The Louisiana Weekly for a woman to join the Creoles. The team owner thought having a female presence on the club might pique potential fans’ curiosities and entice them to games.

“He thought that would be the come-on,” Ackmann quotes Bland as saying.

As it turned out, Page ended up not having to look very far for a woman prospect – Bland was already working as a cashier at the Page Hotel.

“Lucille Bland loved sports, played basketball and baseball at Dillard [University, an HBCU in New Orleans], and read everything she could about her hero, Babe Didrikson Zaharias,” Ackmann wrote.

While Page insisted that Bland (at that time Herbert) stay attractive and “stylish” on the field, she knew how to entertain a crowd, and as a result she wasn’t afraid to “get right in an umpire’s face and let him have it,” Bland said.

She noted that at first the other players weren’t thrilled with her presence – “they resented it immensely” at first – but once she proved to them that she was a baseball junkie who knew the game front to back, they became more comfortable with her around and accepted her suggestions. “I was a sister to them,” Bland told Ackmann.

The first mention of Herbert I found in the media outside of New Orleans in 1947 came in mid-May, when the Morning World newspaper of Monroe, La., mentioned her in a preview article about the Creoles’ upcoming game against the Cinderella Sports of Monroe.

“A feature of the Creole outfit is its woman coach, Lucille Hebert [sic], who will operate from the first base coaching box when her team is at the bat,” stated the World.

The national press apparently caught wind of Lucille’s presence with the Creoles in mid- to late-July, when several papers from outside Louisiana, as well as multiple national Black wire services, reported on her position with the New Orleans club.

An Associated Negro Press dispatch from July 21 noted that “[n]ovelty has been added to baseball by the New Orleans Creoles, members of the Negro Southern League, in Miss Lucille Herbert, and attractive 24-year-old graduate of UCLA who travels with the club and acts as coach.”

It added that “[h]er hobby is sports and she played softball, basketball and a number of other sports. …

“[S]he hopes to land a post in a city playground or recreation center, but, until then, watch her on the first base line with the Creoles.”

The Los Angeles Tribune, another Black paper, published a sports brief about Herbert, noting that she was a student at local schools, Los Angeles City College and UCLA, and graduated in physical education from the latter institution. Being a coach, the paper stated, gave Herbert “one of the most unique jobs held by a woman.” The publication added that Lucille “plays baseball herself.”

Unfortunately, many of the media references to Herbert included commentary about her looks and attractiveness, including a column by my journalistic hero, the Baltimore Afro-American’s Sam Lacy.

“Southern League teams are whistling at the first base coach of the New Orleans Creoles,” Lacy wrote in the Afro’s July 26 issue. “He’s a she, 24-year-old Lucille Herbert, beauteous UCLA graduate.”

A short essay about Lucille can be found on the Web site for the Center for Negro League Baseball Research. The essay states that Bland “was an outstanding all-around athlete” who was selected by Page “as a third base coach/traveling secretary/player because of her athletic ability, her bubbly personality and her administrative skills.”

The CNLBR piece adds:

“As the Creoles’ third base coach Lucille was said to have put on quite a show when New Orleans was up to bat. Her confrontations with the umpires were said to have been quite a spectacle. Lucille’s fiery demonstrations always kept the fans entertained. She was very popular with the players, fans and media. A picture of Lucille in her Creoles’ uniform was even featured on the cover of the [team’s] program in 1947.”

The short article underscores that she was a well known figure in the New Orleans community by showing pictures of her in her Creoles uniform mentoring kids during a baseball camp at Pelican Stadium in June 1947.

After her tenure with the Creoles, Lucille stayed active in the local community; she attended Dillard, where she starred in basketball, and she later helped perform fundraising for the school. She also participated in a voting registration drive, sponsored by the Pontchartrain Park Homes Improvement Association in 1961, during the Civil Rights Movement.

Lucille achieved one of her goals when she earned a position as a recreation supervisor with the New Orleans Recreation Department in 1952. As part of the job, she coached the girls basketball team at the Rosenwald Recreation Center, for example. Unfortunately, though, she was dismissed from the job in 1957 for specious reasons put forth by the NORD supervisor, who was the son of the department’s executive assistant director.

Later on, Bland headed back to California, where she earned a master’s degree from Pepperdine University and spent her career in the education field. However, she maintained a home in New Orleans.