Update, July 18, 2025: Since first posting this a few days ago, I’ve gathered a lot more information — namely, game coverage and box scores — that fills in Alexander Albritton’s baseball career significantly. A more detailed explanation can be found later in this post, and I plan on eventually doing an additional, separate post that includes a bunch of newly gathered stuff about Albritton, the baseball player. For now, read on …

To follow up on my previous post updating the tale of Negro Leagues pitcher Alexander Albritton, who was beaten to death at a psychiatric hospital in Philadelphia in 1940, something I wrote about in these previous blog posts here and here, and in this article on philly.com, the Philadelphia Inquirer newspaper’s Web site. (Unfortunately the article is behind a paywall, though.)

This second installment gets back to basics a bit, shall we say, and away from depressing ghost stories by looking at Albritton’s actual baseball career and his performance on the field before he left the game.

Albritton was born in February of either 1894, 1896 or 1897 (depending on the source), making him in his early- to mid-20s in the first coverage of his playing career that I found.

That would be in May 1918, when Albritton took the mound for the Bacharach Giants of Atlantic City against the 349th field artillery team from nearby Camp Dix. The Giants nipped the Army team, 6-5, and Alexander whiffed four and walked six. At the time, the Bacharachs were a top-flight independent team based in Atlantic City, N.J.

But by August of that season, Albritton had skipped to the Black Sox of Camden, N.J., for whom he hurled a two-hit gem over a team from Chester, Pa., in a 7-2 victory. The Camden Courier-Post stated that the Chesters “were simply baffled at the bat by pitcher Albritton,” who produced some “clever twirling.”

However, a couple months later, Albritton was suiting up for another independent, largely barnstorming aggregation, the Pennsylvania Giants, who voyaged to Reading, Pa., where they played a local club, the Kaufmann Professionals, a team representing a furniture store, in a pair of games. Both contests actually went into extra innings, with the teams splitting them.

(The Pennsylvania Giants seem to be completely distinct from the earlier, juggernaut Philadelphia Giants, an independent professional team that was loaded with Hall of Famers and should-be HOFers.)

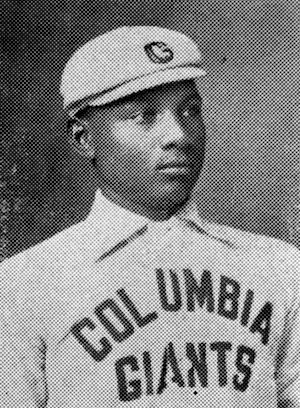

For the 1920 season, Albritton caught on with a team called the Pittsburgh Stars – likely the Pittsburgh Colored Stars of Buffalo, N.Y. – who were led by the great, ageless Grant Johnson, a turn-of-the-century star infielder who by then was pushing 50 (and who needs to be inducted in Cooperstown, like, yesterday). Albritton also apparently played left field for the Stars, but by the end of the season, Albritton was back with the Pennsylvania Giants, where he also suited up at first base on occasion.

It looks like Alexander started the ’21 campaign signed to the Buffalo club again, but he was lured away to the national capitol by the Washington Braves, who, according to contemporaneous reports, played in something called the Colored Professional Baseball League. I’ve never heard of a league in the 1920s with that precise name, and I doubt the media meant the first Negro National League, then in its second season.

Anyway, with the Braves, Albritton showed the talent that secured him a place in professional Black baseball. In late April, he hurled a three-hit, nine-strikeout, shutout gem to beat a team called the Brooklyn Slides, 4-0; a few weeks later, the Braves’ shoddy fielding let down Albritton, who held the Buffalo Stars (his previous team) to four hits in Washington’s 2-1 loss.

Fortune soon turned in Albritton’s favor. On May 18, 1921, he engaged in a pitchers’ duel with Hilldale’s Phil Cockrell before faltering in the later innings and suffering a 7-2 loss to the Darbyites.

At the time, the Philadelphia-based, then-independent Hilldale Club was one of the best teams in the country, and they apparently liked what they saw in Alexander Albritton, because 10 days after his hard-fought loss to the Darbys, he was on the mound, albeit for less than an inning, for Hilldale in its 10-9 triumph over the Norfolk Giants.

Two days after that, Albritton earned the starting nod on the hill for Hilldale in the front end of a doubleheader against Norfolk; Albritton claimed a 7-4 victory, which the Darbyites followed up with an 11-4 win in the second game.

He seems to have stayed with the Hilldales throughout the rest of the 1921 season, putting forth performances plagued by inconsistency. At times, he showed flashes of brilliance at times, such as his “airtight pitching” in a 2-0 blanking of a company team in Philly, according to the Philadelphia Inquirer.

But at other times, his pitching was certainly less-than-stellar, like when he got drubbed by a team called the Fleisher Yarners in Bristol, Pa. The Lancaster News-Journal summed it up nicely: “The ‘Yarners’ took a liking to Albritton’s offerings and knocked him out of the box in the first.” (Fleisher scored five times in the opening frame.)

In 1922, Albritton jumped to the Baltimore Black Sox, but I could only find one game in which he played – a late-August encounter with a local team, Public Service, in Camden, N.J., in which Albritton hurled a complete-game, seven-hit victory over the “Postscripts,” according to the Camden Courier-Post.

I could find no more mention of Albritton in the press until the following March, when the Courier Post reported that he had signed again with the Camden Black Sox. The newspaper asserted that Alexander would be the ace of the pitching staff.

However, the next time Albritton pops up is in May 1923, when he’s pitching for the Washington Potomacs, an independent team led by none other than future National Baseball Hall of Famer Ben Taylor.

With the Potomacs, Albritton pitched to a 4-4, darkness-ended tie with the Richmond Giants on May 18. Then, during a series of games with the great Harrisburg Giants, who at the time were also an independent club, one that included legendary outfielders and should-be Hall of Famers Rap Dixon and Fats Jenkins. (One year later, when the Giants entered the new Eastern Colored League, Dixon and Jenkins were joined in the outer garden by Oscar Charleston, many folks’ – yours truly included – choice for baseball GOAT of any era, league or color. That trio also ranks among the great outfields of all time – the greatest, according to some.)

One of the Washington-Harrisburg clashes came on Independence Day in D.C., with a doubleheader. Albritton pitched the first contest and got tagged with the 5-2 loss.

For the next five weeks or so – into late August – the Potomacs seemed to have played largely teams far from major-league level, such as company squads and town/city clubs. And in general, Alexander gave a good account of himself. Against a Philadelphia department store team on July 21, Albritton “was in wonderful form and did not yield a hit until … the seventh,” stated the Philadelphia Inquirer of his 3-0 victory; in Mount Holly, N.J., against a town team, Albritton “tightened up in the pinches” in posting another 3-0 W, according to the Pittsburgh Courier.

The Seamheads database paints a bit of a different picture, however. The Web site has the Potomacs going 14-20, with Albritton posting a record of 0-4, with a staggering 8.61 ERA, only five strikeouts and a horrendous WHIP of 1.783.

(If media reports are to be believed, though, the situation got a little better later on in the season, with the Aug. 25 Norfolk Journal and Guide, in describing the “rejuvenated” Potomacs, called Albritton “one of the leading pitchers in the East.” The Washington Evening-Star, one day later, asserted that “the local club has one of the best pitching corps in the colored league.”)

But Albritton then seemingly jumped back to the Baltimore Black Sox, because on Sept. 9 he came on in relief in the ninth to clinch the 12-8 triumph over the New York Lincoln Giants in the Big Apple. That Lincoln Giants club was absolutely loaded, with pitcher-manager and eventual Hall of Famer Cyclone Joe Williams (who got tagged with the loss in that 12-8 game), plus three guys who should be in the Hall in Oliver Marcell, George Scales and Spot Poles. (It also had star pitchers Bill Holland, Sam Streeter and Dave Brown.)

The 1924 baseball campaign seems to have started with a bit of equivocation for Alexander Albritton. Multiple media reports in April ’24 stated or hinted that he was uncertain with whom he’d sign – possibly with the Philadelphia Giants, possibly re-signing with the Potomacs, maybe with the Newark American Giants.

Pittsburgh Courier columnist Rollo Wilson, for example, wrote in early April that “Albritton … is undecided where he will twirl this summer. He is considering an offer to go up into New York state, he says.” But then, less than a week later, a newswire service reported that Albritton had committed to pitch for the Newark American Giants “but as yet has not sent in his signed contract.”

He landed with none of those. Instead, in 1924 Albritton initially suited up for the Brooklyn Cuban Giants, apparently a new, independent team that was distinct from the Brooklyn Royal Giants of the ECL. He pitched for them in a 2-0, 14-inning win over the Charleston Giants, as well as a 19-6 triumph over the Wilmington Professionals. Both games took place in May.

(Interestingly, on May 24, 1924, the Philadelphia Tribune asserted that Albritton “is the pitching ace of the Giants” and called him a “spit ball artist.” I’d never seen him reported as a spitball pitcher before I found the Philly Tribune article in question.)

However, he once again jumped ship and apparently left the Brooklyn club for a team called the Pittsburgh Giants; on June 22, he pitched for his new team in their 11-1 drubbing at the hands of the General Tire company team in Akron, Ohio.

And a month later, Albritton was back with the Washington Potomacs, who were again piloted by Ben Taylor. There was a key difference in the setting, though – in 1924, the Potomacs were no longer an independent team, but instead members of Ed Bolden’s Eastern Colored League, one of the seven Negro Leagues now officially recognized as major leagues. That would seemingly make Alexander Albritton an actual major league baseball player. But we shall see.

And a month later, Albritton was back with the Washington Potomacs, who were again piloted by Ben Taylor. There was a key difference in the setting, though – in 1924, the Potomacs were no longer an independent team, but instead members of Ed Bolden’s Eastern Colored League, one of the seven Negro Leagues now officially recognized as major leagues. That would seemingly make Alexander Albritton an actual major league baseball player. But we shall see.

In practical terms, Albritton was back in action under a skipper he knew and hopefully was used to. The Courier’s Wilson wrote on July 19, quizzically, that Taylor plucked the battery of Albritton and catcher Willie Creek from the Homestead Grays, who at that point had yet to become the major-league powerhouse they were in the 1930s and ’40s. In 1924, the Grays were still growing and gestating toward their golden era. However, I’ve found no proof, i.e. game coverage or printed game box scores, of Albritton actually suiting up for Homestead. Anyhoo, Albritton appears to have finished the 1924 campaign with the Potomacs.

For the following season, 1925, Albritton reportedly began the season with the Potomacs. In early February, Rollo Wilson penned that in ’24, “Albritton proved one of the steadiest men of the [pitching] staff.”

Returning Washington manager Taylor, in an article in the Baltimore Afro-American attributed to himself, acknowledged that the Potomacs had been a mediocre venture on the diamond during the previous two seasons and would need significant adjustiments and additions for the ’25 season to be any better than the club’s previous couple summers. Taylor noted that he first inked Albritton to the Potomacs in 1923 and that the Philly lad would be back in 1925.

The ’25 season, though, didn’t work out as planned for the Washington Potomacs – by June, they’d abandoned the nation’s capital and moved to Wilmington, Del. But Albritton, along with the rest of the Potomacs, soldiered on, and on June 8 he earned a 7-6 victory over the Mahanoy City (Pa.) Blue Birds, despite inconsistency on the mound.

“‘Twas a game of good baseball, bad baseball, good pitching, bad pitching, and much heavy hitting …,” reported the Mahanoy City Record American.

“Neither Albritton nor (Blue Birds pitcher) Knetzer looked any too steady out on the hill,” the newspaper added, “each allowing five passes in addition to the heavy and sincere clubbing. Both were in to stay the limit, however, and both worked hard.”

Actually, Albritton was the article’s lead, starting with the first paragraph. Unfortunately, the report was dotted with some verbiage that is now woefully outdated and offensive. (That’s in addition to the bizarre word salad and questionable grammar.) Stated the initial paragraph:

“Alexander Albritton, looking like a coal yard at midnight in Pittsburgh, brought his rag time [sic] band of Wilmington Potomacs to the West End Park yesterday and pitched his dusky brethren to a 7-6 victory [over] the Mahanoy City Blue Birds in a battle featured by extra basehits [sic]. Alexander the Great emerged victorious over the Flock but not until a torrid session that lasted two hours and fifteen minutes and ended with the winning run on second base had been laid before the fans.”

(I’ll note here that in the June 13, 1925, edition of the Pittsburgh Courier, Rollo Wilson asserted that Taylor had actually signed Albritton to the Potomacs in the current year from the Philadelphia Giants.)

The rest of the 1925 campaign proceeded with further inconsistency from Albritton. On June 21, he pitched well in the Potomacs’ 9-3 triumph over a town team in West Lebanon, Pa., but five days later, he looked dreadful against a team in Hazelton, Pa., getting shelled for eight runs in seven innings of work in which he didn’t notch a single strikeout.

As the 1925 season wore on, there was more bad news for the Potomacs – they were forced to drop out of the ECL and revert to a barnstorming, independent team. (Wilson described the newly rebranded club thusly: “Several league discards are on a co-plan team which is laying around the Somnolent City as the Wilmington Potomacs. Larry Somer … has charge of the outfit and is getting them good booking.”) Albritton stuck with the rebranded franchise, however, with continued mixed, often mediocre, results.

But Albritton still couldn’t sit still, and in September 1925, he took the mound for a traveling “all star” team under the managerial eye of grizzled veteran catcher Chappie Johnson, who was approaching the half-century mark age-wise. On Sept. 20, he hurled the the first game of a four-game series between Chappie’s All Stars and a barnstorming team in Binghamton, N.Y., and came away with a complete-game, 7-1 win in which Alexander scattered eight hits.

That’s the last mention on Albritton I could dig up until a few in spring 1927, which places him on another all-star aggregation or sorts, this one led by future Baseball Hall of Famer Louis Santop and apparently based in the small town of Ambler, Pa. Santop called the club the Bronchos, and, per his usual, Albritton was decent but nothing spectacular; in a doubleheader against the spring-training, Ben Taylor-piloted Baltimore Black Sox, Alex picked up the win after going seven innings in long relief against the strong-swatting Baltimore bunch. The Asbury Park, N.J., Press newspaper reported that “as a whole [Albritton] turned in a very credible performance.”

In 1928 Albritton reportedly returned to Santop’s crew, but I couldn’t find evidence of Albritton pitching in a game with the aggregation that year.

And that, as far as I could find, was that for Alexander Albritton’s career on the diamond. Looking back, one question we can maybe ask when summing up Alexander Albritton’s career on the diamond is somewhat basic: How good was he? And, more specifically, was he of major-league caliber?

We can probably trust the venerable writer/researcher James A. Riley, author of the landmark “The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues,” who included a brief entry on Albritton:

“During a five-year span in the early ’20s, he pitched with five different eastern teams, but despite being a hard worker and always ready to pitch, never really made it big. … He was a fair pitcher and could beat the white semipro teams but was not effective against the [B]lack major-league teams.”

From what I could glean, Riley’s assessment is pretty spot on and sums up Albritton’s on-field career perfectly, and that sentiment was generally echoed by Ben Taylor himself, who wrote in his aforementioned, first-person article in the Afro-American in early 1925:

“He is a fair pitcher, but is too light for the big leagues. However, he can beat most any white club and will earn his salary pitching against the semi-pros. He is a hard worker and is always ready to work.” (This might actually be from where Riley got his assessment of Albritton.)

Therein lies a second question we could pose about Albritton – did he ever actually achieve “major league” status?

From what I can tell, and from the record that I found, Albritton did play for a team that is now considered a major league team in the eyes of modern Major League Baseball – for the Washington Potomacs of the Eastern Colored League in 1924. By my tally, every other edition of a given team for which Albritton played was either an independent, barnstorming and/or sub-top level.

However, we should possibly go a bit further to sharpen up the focus even more by making sure that, during that tenure with the major-league Potomacs, did Albritton ever actually pitch against another team that was similarly of major-league level? Or did he personally only ever pitch against lesser opponents in games scheduled between official ECL contests?

The verdict: Albritton never took the mound pitching for an MLB-level team against an MLB-level team.

The verdict: Albritton never took the mound pitching for an MLB-level team against an MLB-level team.

So, he was briefly a member of a team that is now considered major league, but he never pitched in any official fully major-league games.

Thus, the answer to the question of whether Alexander Albritton was a major league player is, as is quite often the case in the Negro Leagues, it’s complicated.

It also must be pointed out that I might have missed a game or two in my research, and that someone might, down the road, uncover proof of Albritton’s fully and unquestionably major-league status.

Update/Edit: Like I noted up top, I’ve learned a great deal more about Albritton’s life on the diamond, such as box scores and game covers, that detail many additional games in which he played over his career. The bottom significance of that is that we can definitively say that Alex Albritton, was, under newly modernized MLB standards, an officially major league baseball player.

Specifically, I now know that Albritton did pitch or otherwise play in several games in which his team was of major-league level, and so was the opponent. The records of these additional major-league games came courtesy of my friend and peer Kevin Deon Johnson, whose own database included these “new” games. Many thanks to Kevin for the input and research.

As stated at the beginning of this post, I plan on doing a separate, more thoroughly post fleshing out Albritton’s career, but for now, I’ll explain how I missed these additional games when I was doing my own research on Albritton.

Basically, I searched the newspaper databases to which I have access for the keywords “Albritton,” “Allbritton” and “Albritten.” The game articles and box scores Kevin possessed featured Alexander listed under an array of other spellings and names — “Britton,” “Britt,” “Al Britton” or some other abbreviation.

I subsequently did my own additional research using those new keywords, and I uncovered a slew of other games in which Albritton participated, many of them against semipro or company clubs.

So keep an eye out for my next post about Albritton’s baseball career. Now, back to this original post …

A final query we could ponder regarding Albritton’s time in baseball is whether he might have shown any flashes or hints of symptoms of the illnesses that would land him in a psychiatric hospital in just over a decade.

Alas, that’s a question that might have no discernable answer, at least at this moment. The coverage of him in his athletic pursuits mentioned no signs of psychological instability or distress that I could find. Moreover, we don’t immediately have access to any relatives, descendants or friends for any testimony, whether spoken or written, as to his health.

In general, though, many people afflicted by mental illness start showing severe, debilitating symptoms in the late teens or early 20s. Depending on the year of his birth, Albritton was in his early- to mid-20s years old at the time of the first game coverage of him, and late-20s-to-early 30s at the time of his last mentioned performance. Why did his career end? Was it his health? Was it by choice? Or was it because, well, he just wasn’t that great a player?

I’ll hopefully be able to more fully dive more deeply into his afflictions, hospitalization and death. But for now, we close the curtain on Albritton’s career pursuing the national pastime.