This post was originally designed to be part of my previous one about the details of Alexander Albritton’s death and the blanks that still need to be filled in more than eight decades later. The idea was to segue from the grim specifics of the death of one patient at Philadelphia State Hospital, commonly known as Byberry hospital, into a discussion of the horrific conditions in general at Byberry and the myriad tragedies that took place there in its long, troubled history.

But the post just grew longer and longer, and potentially more tedious. Plus the stuff in this new post doesn’t directly involve Alexander, but instead subjects kind of tangential to him. So I decided to break this off into a sort of postlude or sidebar to the previous, main post about Albritton’s death.

**********

Warning: This post contains information and photos that might be disturbing to some readers.

In the larger view, Alexander Albritton’s tragic death served to underscore the fact that Philadelphia State Hospital, commonly known as Byberry, was rife with deplorable conditions that most likely led to Albritton’s death – and the deaths and suffering of countless others.

Albritton’s violent demise prompted a local military veterans leader to publically call on the four Black members of the state legislature from Philadelphia to demand an investigation into the conditions at Byberry.

The question soon became how, exactly, the conditions at the hospital were such that a single attendant was monitoring an entire ward; why the injuries that caused Albritton’s death went undiagnosed and untreated for two-plus days; and how and why Albritton ended up dead, sitting on a bunch, unnoticed?

Some of the most piercing criticism was leveled by Deputy Coroner Vincent Moranz, who told the Philadelphia Tribune that the “(t)his system is obviously undermanned and underpaid. If there were more attendants, it would not be necessary for one attendant to take such strenuous measures in handling persons like Albritton.”

Moranz added that Weinand was “the victim of a system which fails to provide proper supervision over its charges.” The Tribune also noted that Genevieve Davis, the supervising nurse general at the hospital, stated (it’s unclear exactly when and where she gave this testimony) that the facility only had three doctors and seven nurses caring for more than 1,000 patients.

The Pittsburgh Courier reported on a recent report stating that recently, Byberry had been seeing a death every week to 10 days, and it took only an astonishingly short time for another questionable, violent death to occur at the institution; less than an hour after Albritton was found dead, 61-year-old Francis Hughes succumbed to injuries suffered about a month earlier in a scuffle with Alfred Gilmore, 46, that took place roughly 24 hours after the latter was admitted to the hospital.

The tragic pattern continued seemingly ad infinitum throughout the hospital’s history, both before and after Albritton’s death, from the facility’s opening in 1911 and the closure of its last buildings and wards in 1990. In June 1938, the Philadelphia Inquirer published an investigation by reporter John McCullough, who toured both Byberry and Norristown State Hospital, another large psychiatric facility in Pennsylvania. In comparing the two hospitals, McCullough gave a largely positive review of Norristown, but leveled substantial criticism at Byberry, which he said featured such apathy and disregard toward patients by the staff, the facility seemed like it was in the diseased “dark ages” compared to Norristown.

About a month after the Inquirer’s article, the state legislature released its own, scathing study of Byberry, dubbed the Shapiro Report, which, another Inquirer article stated, “literally crawl[s] with ghastly detail of incompetence and mismanagement and their selfish perpetuation, coercive administration and medical irresponsibility, professional misconduct, and bland and persistent toleration of mistreatment and the lack of treatment of the 5400 helpless inmates.”

In particular, the report mercilessly ripped into hospital superitendent Wilbur Rickert, who was described as grossly incompetent and infuriatingly indifferent to the suffering of thousands of patients.

An editorial in the July 22, 1938, issue of the Inquirer did not pull any punches on that last count, asserting that Rickert had made a “disgraceful botch” of administration at the beleaguered facility.

“The Legislative Committee minces no words about the superintendent’s unfitness,” the editorial stated, “and upon his shoulders it places full responsibility for conditions that are made up of inefficiency, cruelty, intrigue and barbarity reminiscent of the dark ages. It is an appalling line of soiled linen that the report stretches in public view. It is not pretty to look at, but it has to be seen if the full story of Byberry and its shame is to be comprehended.”

The report also strongly recommended that the state take over the administration of the hospital from the city, a move the Inquirer’s editorial page praised and raised hope for a radical rectification of the terrors at Byberry.

This firestorm came less than two years before Alex Albritton was fatally beaten within Byberry’s walls, and in the dozen or so years following the former baseball pitcher’s death, the continuous line of tragedies did not abate immediately after state takeover.

In January 1941, in fact, Time magazine published an article about Byberry, to report on the progress, and lack of further progress, under Woolley, the man who had been appointed by the state to “clean up” the nighmarish conditions at the facility.

The Time story largely painted Woolley in a favorable light, describing him as a beleaguered administrator hamstrung by paltry funding and a swelling patient population that had reached about 5,800 against a capacity of less than half that. Woolley stated that while some progress had been made, the conditions were still embarassingly dire.

“When I came here Byberry was a medieval pest house,” the magazine quoted him as saying. “It’s now the equal of an 18th-Century insane asylum. It’s a disgrace to any community or government which calls itself civilized.”

Nearly 80 years ago, in 1946, Life Magazine – at the time the country’s premier general-interest publication – ran a lengthy expose of the nation’s psychiatric wards and mental hospitals, including those in Pennsylvania. Referring to the facility by the nickname given to it by its patients – “The Dungeon” – reporter Albert Q. Maisel wrote that “[i]n Philadelphia the sovereign Commonwealth of Pennsylvania maintains a dilapidated, overcrowded, undermanned mental ‘hospital’ known as Byberry.”

In July 1988 – roughly two years before Byberry closed completely and for good – the Inquirer ran a comprehensive investigative package detailing all the social, cultural, economic and political factors that created the hospital’s horrors.

Included in the reporting was a necrology – a list, far from complete, of dozens of violent deaths and suicides ending in 1970. The distressing listing included 28 such incidents in the 11 years following Albritton’s death, culminating in February 1951, when four female patients were killed in a fire caused by arson on the part of other inmates. (Following the fatal fire, the hospital declared it would, in addition to investigating the blaze, examine 10 other recent deaths at the asylum.)

That section of the necrology included two male orderlies – one dishonorably discharged from the Navy, the other a former prizefighter dubbed “the Slugger of Byberry” – being convicted of the manslaughter of a patient; at least five suicides; and six patients whose bodies were discovered in various places after going missing from between two days to a month.

Byberry’s history did include occasional periods of improvement, thanks to developments like new building construction, other infrastructure projects, and the introduction of newer, more holistic and humane treatment practices. Some accounts reported that the situation improved gradually after state takeover. But dark stretches and horrific tragedies consistently continued to take place throught Byberry’s often macabre history.

The Ancient History/Ancient Myths Facebook page includes a short essay on Byberry and pointedly states how the notorious hospital “didn’t just confine the mentally ill—it locked away the vulnerable, the unwanted, and the forgotten. Overcrowded, understaffed, and poorly managed, it became a dumping ground where basic human rights were routinely violated. Patients were often left unclothed, unfed, or shackled in filth.”

The essay summed up the hospital’s social significance and historical legacy, stating:

“Byberry wasn’t just a failure of mental health treatment—it was a mirror held up to a society that chose to look away. A place where suffering was hidden, silenced, and normalized. Its eventual closure in the 1990s came far too late for those who endured its cruelty. Today, the ruins of Byberry stand as a decaying reminder of how institutions, left unchecked, can become prisons of torment rather than places of healing.”

In the Inquirer’s article from 1988, writer William Ecenbarger eloquently described the lingering, seemintely infinite impact had on the City of Philadelphia, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, and the nation’s mental-health system:

“… It was opened in 1907 and operated much of the time on the theory that circumstances that would drive a sane person mad might drive a mad person into sanity.

“Byberry. Like the Holocaust, it is impossible to amend, impossible to accept. … Perhaps we should allow it to stand out there on Route 1 as a reminder that in a bureaucracy, there is no problem too big to be avoided; that the humans given responsibility for other humans cannot sit back and admire their intentions; that injustice always walks softly – and we must listen for it carefully.

“Byberry. It pulls you in and wrings you out like a rag. It’s a lake where all the world’s tears have flowed. The history of Byberry reads as though it were written by Dante, and then rewritten by Kafka with Poe looking over his shoulder. Byberry’s story is freighted with tragedy. All institutions fall short of the aspirations of those who create them, but seldom in the 20th century has this occurred with such devastating effect on its guiltless residents. There are a few heroes, and they’re not hard to spot. And like all true stories, this one has no end.”

**********

Let’s digress a little and look into who the other person in the scuffle that killed Albritton was.

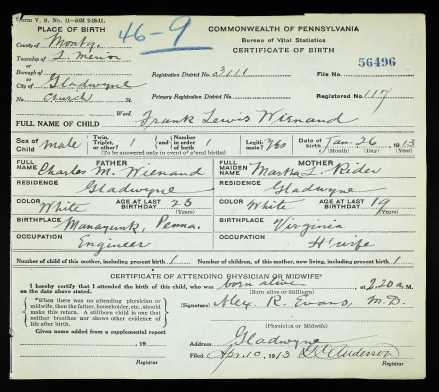

Frank (sometimes stated Franklin) Lewis Wienand (some documents and articles say Weinand) was born on Jan. 26, 1913, in Gladwyne, Pa., in Montgomery County to Charles Wienand, an electrical engineer for a paper company, and Martha Wienand, nee Righter, a housewife. Frank was a third-generation German-American; his paternal grandparents immigrated to the United States from Deutschland, probably between 1881 and 1884. (Montgomery County is adjacent and located to the north and northeast of Philadelphia County.) I wasn’t able to find out much about Martha Righter Wienand, other than she died in 1973. (Charles died in 1944.)

The family – including Charles Sr., Martha, Frank and younger brothers Charles Jr. and William Lloyd – apparently shuttled back and forth between Montgomery County, Pa., and Philadelphia during Frank’s childhood. Frank was the oldest of the three boys.

By 1940, Frank was living in Bucks County, Pa., adjacent to Philadelphia County to the northwest, and commuting to work at Byberry Hospital. His wife, Mary Stella Wienand (nee Herner), was also an attendant at the hospital and was a second-generation Polish-American. However, it must be noted that there exists discrepancies between various documents about Frank Wienand’s adult life, not the least of which is the different spellings of his name. Most of the contemporaneous articles I’ve found spell it Weinand, while many official documents, as well as a large family tree on Ancestry.com, spell it Wienand. Some sources list it as Wienant and Weinard, too.

In Frank and Mary’s listing from the 1940 federal Census, dated April 9, 1940, two months after Albritton’s death, the couple is living in the Bucks County township of Middletown. However, on Frank Wienand’s World War II draft card, which is dated Oct. 16, 1940 – roughly eight months after the death at Frank’s hands of Alex Albritton – Frank reported that he lived in the borough of Langhorne, in Bucks County, and was still employed at Byberry.

After all the furor and, presumably, legal wrangling over Albritton’s death and the abhorrent conditions at Byberry – although criticism of the hospital would continue as long as it remained open, and even long after – Wienand seems to have had a relatively normal life.

Frank and Mary apparently had three children at some point – Frank Jr., Robert and Terry – and they were members of Langhorne Presbyterian Church for a while. There are scattered indications that the couple lived in Penndel and Hulmeville, additional boroughs in Bucks County. In 1962, Frank was called to jury duty in Bucks County, and his residence was listed as Penndel.

Mary Wienand died in December 1968 at the age of 61 from a heart attack. However, I’ve been unable to pin down for certain where and on what date Frank himself passed away; most likely he died in Langhorne, but while his Social Security records state that he died in December 1980, his precise date of death has eluded me. Those Social Security records list his last place of residence as Langhorne. (One curious detail from the federal records says Frank’s Social Security number was issued in Texas before 1951. I’ve found no other evidence that he lived in Texas or had any solid connection to the Lone Star State at any time.)

Pingback: Alex Albritton’s brief major-league career | The Negro Leagues Up Close