“The Negro league’s like a light somewhere. Back over your shoulder. As you go away. A warmth still, connected to laughter and self-love. The collective black aura that can only be duplicated with black conversation or music.”

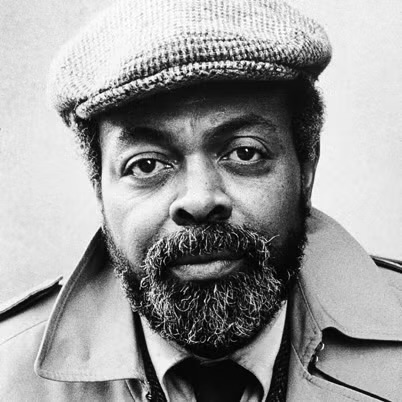

— Imamu Amiri Baraka, in his autobiography

Here’s another quick placeholder post based on random databases that caught my eye while I work on longer projects. This one is about Imamu Amiri Baraka, an influential and often controversial poet, author, thinker and cultural commentator, often dubbed the poet laureate of the Black Arts Movement and a key figure in the overall Black Power Movement.

The database in question is Baraka’s career and personal papers. I first learned about Baraka more than 20 years ago during my time in grad school at Indiana University when I was working on what I had hoped would be a dual master’s in journalism and African-American Studies. (That never came to be, sadly. The School of Journalism was recalcitrant the entire way and in effect blocked me from finishing the AAS half of my degree. And actually, if there’s anyone who knows a relatively simple, low-cost way of finishing my AAS master’s, please let me know!) My professors Fred McElroy (RIP), John McCluskey and Portia Maultsby were keys to my education about Baraka.

The papers in the online archive include interviews with Baraka and other people close to him and involved in the Black Arts Movement and Black Power Movement. One such Q&A was conducted in January 1986 by Komozi Woodard, a prolific author who’s currently a history professor at Sarah Lawrence College.

At one point in the interview, Baraka discusses his childhood watching Newark Eagles games and seeing the players in person.

(Editor’s note: I’m quoting these interviews more or less verbatim from the digital versions that exist in the Baraka papers. The text is probably from a direct transcription, so the grammar isn’t great and many of the names and places aren’t included or are spelled incorrectly.)

Here’s one excerpt:

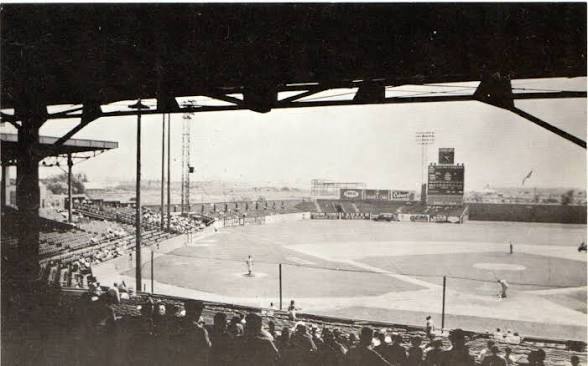

BARAKA: … [W]hen there was black baseball before integration killed black baseball and our players began to play with those other folks, Newark was the world champions, the last year of the black baseball league Newark Eagles were the world champions.* Down at [left blank, but presumably Ruppert] Stadium, the bloods took the seats, these cushions they were sitting on and threw them all out in the field. But it was a hotel called the Grand Hotel on Market Street, a black owned hotel on West Market Street; right there now where they are going to build the vocational school, right across from there right in the Grand Hotel where all the baseball players and the fast light people used to hang out. My father used to take me there because we used to go see black baseball every Sunday. Whenever the Eagles were in town we would go down there. And afterwards they would go up there and have a little drink and he would walk me around. This is Monty Irving [sic] this is Larry Doby, Pat Patterson and I got to meet all those …” **

(*The Eagles actually won the title in 1946, two seasons before the second Negro National League’s demise in ’48.)

(**Baraka expanded on these thoughts in his autobiography. For more info on that, see the end of this post.)

The database’s files also feature an interview conducted by Woodard of Honey Ward, a friend of Baraka’s and an influential Black rights and urban-renewal advocate in his own right. Ward was born in Key West, Fla., but he and his family moved to Newark when he was 2. Here’s an excerpt of that interview:

KOMOZI: Were there a lot of black sports institutions in Newark at that time?

HONEY: Well you had your oldtimers, you had baseball like the Homestead Grays and the Newark Eagles and you had the Kansas City Monarchs that Satcho [sic] Paige came out. Marvin Irwin [sic] played with the Newark Eagles. Larry Doby came out of a black team. Jackie Robinson even played in the black league. The New York Black Yankees and down in [Ruppert] Stadium which is torn down which was owned by the Newark Bears [a longtime white minor-league team] … . My father would take us down on Sundays to see, Ray Dandridge’s father [?] they were baseball players. I remember seeing Satcho Paige playing down there on Sundays, it was all black.

KOMOZI: Were there a lot of people down there?

HONEY: Yeah, the blacks would go down there and watch black baseball because at that time baseball was jim crowed too. Blacks were [not] allowed to play in the majors, the white majors.

Baraka’s papers included references to other authors’ works that themselves mention Black baseball. In notes on Robert C. Weaver’s 1948 book, “The Negro Ghetto,” Baraka lays out this direct quote from Weaver’s book:

“Newark’s deterioration dates from the 1930s, at a time when there was often-repeated praise for the fine department stores, the great insurance companies, the excellent schools, the cleanliness of Broad Street, the influence of its newspapers, and even the vaunted abilities of the Newark Bears, the finest minor league team that baseball had ever seen. [The] [I]nept, politic-ridden [sic] government did little to stem the tide of decline after World War II.”

The database documents also include brief references to baseball in general as a potential source of political activism and focus of efforts toward racial and social justice. Particularly, Baraka’s commitment to communism and Marxism appears to have led him to write his own work as well as examine and cite the texts of other communists in America. And, quite naturally, baseball inevitably, if briefly or tangentially, intersects with such topics. (For example, one of the most passionate and forceful advocates of integration in major league baseball was Lester Rodney, the sports editor of the communist newspaper The Daily Worker, who played a key but somewhat unsung role in the successful entrance of African Americans into Organized Baseball.)

Thus, it’s not surprising that Baraka’s papers, for example, feature a copy of a 1933 essay, “The Struggle for the Leninist Position on the Negro Question in the U.S.A.,” by Harry Haywood, a lifelong, staunch Stalinist/Maoist thinker, writer and activist.

In the essay, Haywood outlines, point by point, the communist platform as a means toward racial and social equality and justice, and one of the points involves sports and athletics, including baseball. In the essay, Haywood wrote that communists demand:

“The right of Negro athletes to participate in all athletic games with white athletes, including rowing, swimming, inter-collegiate basketball, football, major league baseball, etc.; against Jim-Crow policies of the AAU in swimming pools, etc.”

Also found in the Baraka archives are issues of “Main Trend,” a publication of Baraka’s Student Organization for Black Unity (SOBU) and Youth Organization for Black Unity (YOBU) from 1978-81. One of the editions features an article titled, “Baseball Belongs to the People,” which goes through the history of the national pastime – from its professionalization and early attempts at players’ unions in the 19th century, through the reserve clause, commercialization of the sport, segregation and desegregation, and the advent of free agency.

Overall, the article heavily criticizes the team owners and other powers-that-be – the piece dubs them “the capitalists” – in the sport for exploiting both the players and the fans to maximize profit and enrich the owners’ own coffers.

“The history of professional baseball cannot be separated from the history of capitalist exploitation in the U.S.,” the article stated.

However, the article also stresses that for as long as capitalists have allegedly tried their damnedest to treat baseball as their own personal piggy bank, “the people” – the players and fans – have been resisting and fighting for their rights and their share of the proverbial baseball pie. It concludes:

“So long as there is exploitation in baseball there is resistance to exploitation. And it is up to us to support this resistance. Us – be people who invented baseball and who fill the rosters of every team in the major leagues. Us – the most exploited and most revolutionary class in capitalist society.

“Baseball belongs to the people!” [italics in original].

As part of its analysis and repudiation of extreme, unjust capitalism in the national pastime, the article notes that during the late 19th century and into the 20th, as the owners were tightening their grip on the game, “[I]t was during this period that racism ‘triumphed’ [quotes in original] in professional baseball, as the owners refused to hire black players, condemning them to the Negro Leagues until Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in 1947.”

The piece also refers to the court fight of Curt Flood, a Black player who unsuccessfully challenged the major leagues’ stifling reserve clause. It also asserts that “racism is still rampant, despite all the black and Spanish players,” citing lingering pay inequality and the hostility Reggie Jackson received at the time for supposedly getting notorious Yankees manager Billy Martin fired.

**Now, back to Baraka discussing the influence the Negro Leagues had on him and on the African-American community as a whole in, “The Autobiography of LeRoi Jones/Amiri Baraka,” originally published in 1984. (LeRoi Jones was his original name.)

In the book, Baraka further recalls his experiences with his father at Newark Eagles games, and explains why the team, and Black baseball in general, had so much impact on him and the Black public.

“Very little in my life was as heightened (in anticipation and reward) for me as that,” he stated. “What was that? Some black men playing baseball? No, but beyond that, so deep in fact it carried and carries memories and even a politics with it that still makes me shudder.

“But coming down through that would heighten my sense because I could dig I would soon be standing in that line to get in, with my old man. But lines of all black people! Dressed up like they would for going to the game, in those bright lost summers. Full of noise and identification slapped greetings over and around folks. ’Cause after all in that town of 300,000 that 20 to 30 percent of the population (then) had a high recognition rate for each other. They worked together, lived in the same neighborhoods, went to church (if they did) together, and all the rest of it, even played together.

“The Newark Eagles would have your heart there on the field, from what they was doing. From how they looked. But these were professional ball players. Legitimate black heroes. And we were intimate with them in a way and they were extensions of all of us, there, in a way that the Yankees and Dodgers and what not could never be!

“We knew that they were us – raised up to another, higher degree. Shit, and the Eagles, people knew, talked to before and after the game. …

“That was the year they had Doby and Irvin and [Lennie] Pearson and [Bob] Harvey and Pat Patterson, a schoolteacher, on third base, and Leon Day was the star pitcher, and he showed out opening day! But coming into that stadium those Sunday afternoons carried a sweetness with it. The hot dogs and root beers! (They have never tasted that good again.) A little big-eyed boy holding his father’s hand.

“There was a sense of completion in all that. The black men (and the women) sitting there all participated in those games at a much higher level than anything else I knew. In the sense that they were not excluded from either identification with or knowledge of what the Eagles did and were. It was like we all communicated with each other and possessed ourselves at a more human level than was usually possible out in cold whitey land.

“Coming in that stadium with dudes and ladies calling out, ‘Hey, Roy, boy he look just like you.’ Or: ‘You look just like your father.’ Besides that note and attention, the Eagles there were something we possessed. It was not us as George Washington Carver or Marian Anderson, some figment of white people’s lack of imagination, it was us as we wanted to be and how we wanted to be seen being looked at by ourselves in some kind of loud communion.”

Baraka further describes the Eagles, the Negro Leagues and the Black community a fair amount, but I’ll close with his thoughts about Jackie Robinson and integration overall. He was conflicted, to say the least:

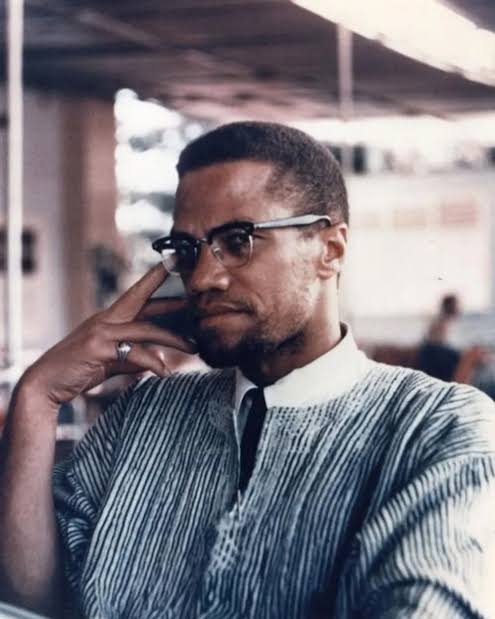

“But you know, they can slip in on you another way, Bro. Sell you some hand magic, or not sell you, but sell somebody somewhere some. And you be standin’ there and all of a sudden you hear about – what? – Jeckie Rawbeanson. I could tell right away, really, that the dude in the hood had been at work. No, really, it was like I heard the wheels and metal wires in his voice, the imperfected humanoid, his first words ‘Moy nayhme is Jeckie Rawbeanson.’ Some Ray Bradbury shit they had mashed on us. I knew it. A skin-covered humanoid to bust up our shit.

“I don’t want to get political and talk bad about ‘integration.’ Like what a straight-out trick it was. To rip off what you had in the name of what you ain’t never gonna get. So the destruction of the Negro National League. The destruction of the Eagles, Greys [sic], Black Yankees, Elite Giants, Cuban Stars, Clowns, Monarchs, Black Barons, to what must we attribute that? We’re going to the big leagues. Is that what the cry was on those Afric’ shores when the European capitalists and African feudal lords got together and palmed our future. ‘WE’RE GOING TO THE BIG LEAGUES!’

“So out of the California laboratories of USC, a synthetic colored guy was imperfected and soon we would be trooping back into the holy see of racist approbation. [Robinson actually attended UCLA, not USC.] So that we could sit next to drunken racists by and by. And watch our heroes put down by slimy cocksuckers who are so stupid they would uphold Henry and his Ford and be put in chains by both while helping to tighten ours.

“Can you dig that red-faced backwardness that would question whether Satchel Paige could pitch in the same league with … who?

“For many, the Dodgers could take out some of the sting and for those who thought it really meant we was getting in America. (But that cooled out. A definition of pathology in blackface would be exactly that, someone, some Nigra, who thunk they was in this! Owow!) But the scarecrow J. R. for all his ersatz ‘blackness’ could represent the shadow world of the Negro integrating into America. A farce. But many of us fell for that and felt for him, really. Even though a lot of us knew the wholly artificial disconnected thing that Jackie Robinson was. Still when the backward Crackers would drop black cats on the field or idiots like Dixie Walker (who wouldn’t even a made the team if Josh Gibson or Buck Leonard was on the scene) would mumble some of his unpatented Ku Klux dumbness, we got uptight, for us, not just for J. R.”

What do you think of Baraka’s controversial take on Jackie Robinson and integration?