I looked through the list of the databases available to me for a quick post while I continue to work on some bigger projects, and the one featuring the FBI’s declassified files and documents from the agency’s decades-long surveillance of the Civil Rights Movement caught my eye.

It’s pretty well known that the longtime and infamous FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover – everybody’s pal, my friend and yours – and his agents kinda had it in for everyone from Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. to Malcolm X to Ralph Abernathy to Huey Newton.

One of the central foci of the chillingly omniscient was the supposed “communist infiltration” of the Civil Rights Movement, including Dr. King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference, or SCLC, as well as the reactionary, bigoted pushback – like the countless bombings and bomb threats – from white segregationists.

So, on a lark, I decided to search through these declassified files to see which famous sporting figures might happen to pop up. I especially looked for Jackie Robinson in them, given his participation in and support of the Civil Rights Movement.

And, wouldn’t you know it, his name does, in fact, pop up a few times in the FBI’s surveillance files.

Now, he doesn’t appear too often, indicating that he seemingly wasn’t a primary focus of the surveillance, but he is in there, unfortunately.

Many of these instances center around his appearances at official SCLC meetings or conventions, including the organization’s 1962 annual national meeting, held that year in Birmingham, Ala., from Sept. 25-28.

In the days leading up to the convention, one confidential FBI communication indicated that Robinson was scheduled to be one of the speakers, along with leading Civil Rights lights Fred Shuttlesworth and Adam Clayton Powell. The surveillance team also stated that their were no demonstrations scheduled by the organizers of the meeting.

Communications after the conclusion of the convention reported that no violence of major incidents occurred during the gathering, and that everything proceeded peacefully. In one memo, an agent described Robinson’s appearance as a speaker: “Jackie Robinson spoke at SCLC banquet night of [Sept. 25] and indicated he wanted President Kennedy to take action in Civil Rights.”

However, an ensuing document reporting on the gathering including much of Jackie’s speech verbatim – it covers roughly two full pages of single-line text, seemingly indicating that the agents focused extra attention on the former baseball great.

In his speech, Robinson urged attendees to support and donate to the effort to rebuild several Black churches that had recently been burned down by segregationists.

“It has been tough for me not to hit back [on news of the burnings],” Jackie said. “Anyone who would burn a church is the lowest type of individual in the world. They must be stopped for America’s sake. …

“My mother told me a long time ago not to go South,” he added. “I kept her advice for a long time. I don’t believe I could turn the other cheek down here. At least that was the way I felt when I saw those burned churches in Sasser, Georgia. … This is all of our fight.”

Those last comments are particularly interesting given that, when he debuted with the Brooklyn Dodgers and throughout his on-field career, he did, in fact, figuratively turn the other cheek while enduring horrific abuse from fans and other players, because he knew that he simply had to do so if he was to succeed, both as a player and a sociocultural trailblazer and bellwether.

Jackie then urged President Kennedy to actively join the fight for justice: “I am not interested in the President’s talk, what we need is action.”

He added that “[T]hey should not worry so much about sending the Peace Corps to Africa, they should send it to Birmingham, Alabama and Mississippi. There are many backward people here. I don’t believe we will continue to permit these people to deny us our privileges and opportunities.”

He expressed his support for the Freedom Riders and obliquely criticized Bull Conner. Robinson concluded his speech:

“Even though I have lost many awards because of my stand, I have not lost my self respect. They tell me that Birmingham is the worst city in the United States. I was born in Georgia but I got away quick. I have seen the love and admiration people have for Dr. King in New York. They have asked him many questions, but have not been able to twist him up. I am sorry we can’t participate more.”

The declassified archive of FBI surveillance documents also included brief references to Jackie in its reportage on the 1964 SCLC Convention, held from Sept. 26-Oct. 2 of that year in Savannah, Ga. The interdepartmental memorandums stressed that organizers of the SCLC gathering had received bomb threats warning of attacks on the convention. However, the agents later reported that the meeting proceeded without incident.

The references to Robinson in the documents were brief and included a notation that a story that had just appeared in the Savannah Morning News; the memo reported that the article had stated that Robinson had criticized Adam Clayton Powell for not being active enough in the Civil Rights fight, to the detriment of the Movement.

The surveillance reportage also stated that news coverage of Jackie’s speech at the 1964 convention had sharply condemned Republican presidential candidate Barry Goldwater and that he had “implored the nation’s Negroes to defeat” the GOP candidate. Such statements are key, given the fact that Jackie had previously supported Republican positions and candidates, including Richard Nixon in the 1960 presidential election.

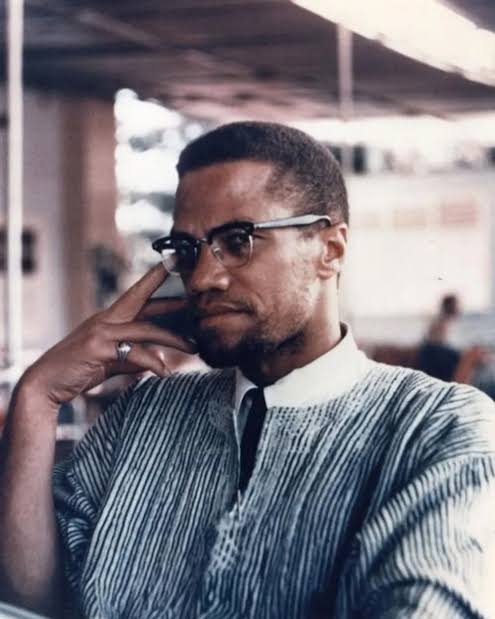

Many of the other references to Robinson in the FBI files centered somewhat around his conflicts with and criticisms by leaders of the Nation of Islam, the Black Muslim organization popularized most prominently by Malcolm X.

Jackie and the Nation did not, shall we say, get along. The former, as reflected in the FBI communications and memorandums, believed the latter was hateful against whites, and Robinson was staunchly opposed to the Nation’s militant advocacy of Black separatism and use of violence in the face of white violence.

For their part, Malcolm X and/or the Nation’s leader, Elijah Muhammad, frequently leveled criticisms toward Robinson, and the FBI’s agents were sure to note it. For example, the federal surveillance documents reported that, on March 9, 1964 – one day after he broke from the Nation of Islam – Malcolm appeared on a news show in New York City and was interviewed extensively by commentator Joe Durso, who at one point in the interview asked Malcolm what the Malcolm thought about Jackie Robinson calling the Muslim leader “a threat to integration.” Malcolm responded by referring to Robinson’s association with then-New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller, a Republican who later became vice president under Gerald Ford.

“Jackie Robinson has just become a part of Governor Rockefeller’s political machine,” Malcolm said, as quoted in the FBI report, “and it is his job to make Negroes think that Nelson Rockefeller is the Saviour [sic] who will lead us to the promised land of integration.”

And, reported FBI agents to their superiors, Elijah Muhammad stated on an October 1965 news program in Chicago that “such prominent [B]lack men Dr. Ralph Bunche, Jackie Robinson and the like only serve the white man and do nothing to better their [B]lack brothers.”

One of the battlegrounds, as it were, of this verbal conflict between Jackie and the Nation was the new media powerhouse that was television. Robinson occasionally appeared on TV news programs that featured a panel of guests discussing the Nation of Islam, Muhammad and Malcolm X, and when Jackie did make those appearances, he was included in the FBI’s surveillance reports.

The declassified archives, for example, include an interdepartmental FBI memorandum describing the now-infamous five-part documentary series on WNTA-TV by broadcast news greats Mike Wallace and Louis Lomax that was broadcast for a week in July 19. The FBI report noted that Jackie Robinson took part in the discussion panel.

Called “The Hate That Hate Produced,” the series examined the burgeoning Black nationalist movements, with much of the focus on the Nation of Islam. (I haven’t seen the series, but from what I gather, it was biased, one-sided and purposefully sensationalistic and inflammatory.)

Finally, the FBI files include a few articles/commentaries written by Robinson and published in various newspapers that were part of the back-and-forth between Jackie and Malcolm in the press. Malcolm X at the time was a lightning rod for controversy, and because of his radicalism, the FBI focused a massive amount of its surveillance on him.

Robinson’s published missives frequently came after Malcolm X had in the media recently vociferously criticized Jackie and other mainstream Civil Rights figures, including, for example, an interview Malcolm gave to reporters in May 1963, and the FBI was quick to note it in one of the agency’s voluminous reports on Malcolm’s words and activities.

In his comments to the journalists, Malcolm asserted that the majority of African Americans who took part in a recent protest in Birmingham rejected Dr. King’s message of non-violence, and the FBI memo noting the statements by reporting that “in the interview … subject had attacked Martin Luther King, Jackie Robinson and [boxing champion] Floyd Patterson as unwitting tools of white liberals.”

One ensuing piece by Robinson, published in the Dec. 14, 1963, issue of the Amsterdam News came in the form of an open letter to Malcolm in which Robinson defends his own record on Civil Rights and the social justice effort, and vociferously criticizes Malcolm’s militancy.

Other published commentaries by Robinson, however, quite significantly came after Malcolm’s March 1964 break with the Nation of Islam, his rejection of Black separatism and the softening of his criticism toward whites. One such column by Jackie, coming in early May 1964, continued to harshly criticize Malcolm, and it blamed prolific media coverage of Malcolm’s earlier, more militant activity and statements, as well as a lack of pushback from society as a whole, for the elevation of Malcolm to hero status.

Then, a July 1964 article published a couple more months later expressed Robinson’s confusion with Malcolm’s break from the Nation of Islam and rejection of hate and violence. In the piece, Jackie wondered where exactly Malcolm now stood on Civil Rights and challenged him to more concretely and decisively state what he now believed. Seven months later, Malcolm X was assassinated.

That’s all I could find in the online archives of the FBI’s declassified surveillance project that targeted Black leaders. But what I did find in the files about Jackie Robinson – who today is almost universally revered as a national hero and beloved by many millions of people in America and beyond – was a little chilling, but it also wasn’t exactly surprising.

The presence of Robinson’s name scattered through these archives perhaps reflects how disturbingly far-reaching and all-consuming that the racist, paranoia-driven federal surveillance effort was. As millions of Americans of all races, ethnic backgrounds, genders, ages, orientations and identities were fighting for social justice and egalitarianism, others were seeing “Reds” around every corner and afraid that society was completely collapsing because of it.

I won’t attempt to make parallels between the Hoover-fueled, half-century-long surveillance of Black Americans and the chaos and reactionary splitting at the seams currently engulfing our society and tearing us asunder.

But feel free to do so on your own, of course …

Home Plate Don’t Move will never be placed behind a paywall, but we certainly welcome donations to the effort. To give to Home Plate Don’t Move and its staff — well, me, the staff is me — go here if you’d want. Thanks, and continued thanks for reading!

Pingback: Legendary writer connects Jews with Black baseball | The Negro Leagues Up Close