So today we have another installment of “cool stuff from various databases.” (I previously did a couple such posts here and here.) I perused a few of them and came across ones compiling the archives of two Jewish newspapers: The Jewish Advocate, based in Boston, and The Jewish Exponent, based in Philadelphia.

I decided to search these archives for articles and commentaries about Negro League baseball, integration of the sport, and race issues in general in the national pastime. I found some pretty good stuff, and I noticed one trend in particular: the columns and articles of Haskell Cohen.

Cohen was an extremely deft, incisive reporter and scribe who’s most well known for his key involvement in the growth and strengthening in the 1950s and ’60s, serving as the nascent league’s publicity director for nearly two decades. He also created the NBA All-Star Game, which he modeled after the MLB All-Star contest.

But he was also a prolific journalist, including as sports editor for the Jewish Telegraphic Agency, a news wire service, for 17 years, and as a contributing editor to several magazines, such as Parade and Spot.

In addition, Cohen founded the United States Committee Sports for Israel (now Maccabi USA); served as the first chairman of the International Jewish Sports Hall of Fame’s selection committee (he’s also an IJSHOF inductee); and was a member of the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame board of trustees, and the U.S. Olympic Basketball Committee.

But for our purposes here, we’ll focus on the reporting and commentaries he provided for the Jewish Telegraphic Agency and various newspapers and similar publications. Through the archives of The Jewish Advocate and The Jewish Exponent, I first collected some columns he wrote for the JTA, then branched out a bit from there.

One running theme in Cohen’s columns was covering the activities of several Jewish executives, promoters and owners in Black baseball, particularly Abe Saperstein of Chicago, Philadelphia’s Eddie Gottlieb, and Syd Pollock of New York, all of whose involvement in Black ball circles, especially as promoters, was somewhat controversial at the time, and continues to be somewhat today.

(Supporters argued that the influence and financial backing they brought to the table was a positive for the Negro Leagues, while critics asserted that the Jewish executives bumped African-American promoters and executives from crucial roles in the sport, exploited Black talent, and siphoned revenue that could have been going to Black-owned teams and promotion services.)

In September 1946, Cohen reported on the financial difficulties being then experienced by Saperstein in Black baseball promotions, including the quick folding of the West Coast Negro Baseball Association, a short-lived league that Saperstein oversaw with Olympic hero Jesse Owens. However, Cohen added that Saperstein hoped to turn things around when he took his Black all-star team to Hawaii for an extended tour. (For more on that Hawaii tour, check out this article.)

In a column from June of the following year, Cohen noted the attendance of Gottlieb and Pollock at the joint meetings of Negro American League and Negro National League in New York City. Cohen also often also reported on Saperstein’s connections as a scout with the Cleveland Indians (now the Guardians), whose owner, Bill Veeck, paid Saperstein to comb the ranks of Black baseball for potential talent for the MLB team; Cohen asserted in a November 1948 column that it was Saperstein who bird dogged Satchel Paige for Veeck and the Indians.

Cohen then, in July 1950, reported that it was now Gottlieb who was promoting Paige; Cohen wrote that “Paige is now under contract to Eddie Gottlieb, who is securing $1,500 to $3,000 weekly for the aged pitcher’s services.”

But Cohen was also willing to take Jewish sports executives to task, such as in July 1945, when he sharply criticized the antics of the Cincinnati Clowns, including relatively harsh words in particular for the team’s owner, Pollock.

“Sid [sic] [has] a funny team but his burlesque of Negro people, for gag purposes, is in very bad taste,” Cohen wrote. “… Sid [sic] is beginning to tone down on this stuff and if he goes all the way in refining his talent[,] the Clowns are really going to come into their own as one of the nation’s funniest ball clubs.”

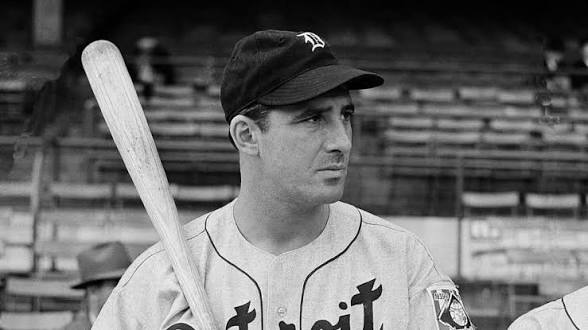

With that, we’ll use a nice segue to Cohen’s occasional mention of who, at that time, was the biggest Jewish name in baseball – Hank Greenberg, of course. In December 1949, Cohen reported how Veeck had sold his interests in the Indians, and the columnist pondered what role, if any, Saperstein would retain with the club, including his activity as a scout of Negro League talent.

But the main thrust of Cohen’s piece was how Greenberg was going to stay on as the general manager for the team, as opposed to the original plan for the Hebrew Hammer, which called for him to be team president.

Then, in February 1951, after the integration of organized baseball had gotten well underway, Cohen quoted Greenberg discussing the latter’s view of racism and bigotry in baseball, particularly in Cleveland, where, Greenberg said, open-mindedness and acceptance were the rule. Cohen quoted Greenberg saying:

“We in Cleveland have adopted the motto that ability counts, not race, color or creed. It is only natural, therefore, that the Cleveland Indians lead the way by judging players on performance only. Our daily lineup includes two Irishmen, an Englishman, a Scotsman and two Mexicans, Protestants, Catholics and Jews, Negroes and Whites and all Americans who work and play together in perfect harmony. This speaks for itself.”

A few years earlier, in May 1947 – just a month or so after Jackie Robinson had stepped on the field for the Brooklyn Dodgers – Cohen noted in a JTA column that Greenberg, and Jews in general, had been steadfast in their support of Robinson. Penned Cohen:

“Jewish baseball fans in Flatbush are keeping a wary eyer open watching the progress of Jackie Robinson, Negro first baseman with the Brooklyn Dodgers. Since the Brooks do not have a Jewish player on the roster, the many Jewish inhabitants of the batty baseball borough, have more or less adopted the colored lad. His every movement on the field and at bat are applauded by the fans who are predominantly of Jewish extraction.”

Cohen added that since his Brooklyn debut, Robinson “has been finding the going rather tough in more ways than one. … As yet, he has not been accepted by members of the league, not even by his own teammates.” However, the scribe continued, Greenberg was one of the solitary figures in the majors “who has extended a welcome hand …”

The scribe added that during a recent contest between the Dodgers and Greenberg’s Pittsburgh Pirates, Robby and Greenberg had collided on a play, soon after which Greenberg had asked Jackie if he’d been hurt in the incident. Robinson said he was OK, and, according to Cohen, “Greenie then remarked, ‘Stay in there, you’re doing fine, keep your chin up.’ These were the first words of encouragement Robinson had heard since the beginning of the season. He told newspapermen: ‘I always knew Mr. Greenberg was a gentleman. Class always tells.’”

In addition to Jewish publications and wire services, Cohen occasionally even did a little stringing for The Pittsburgh Courier, one of the most prominent African-American newspapers of the day.

For example, he covered a Baltimore Elite Giants doubleheader sweep over the New York Black Yankees at Yankee stadium with an article in the May 26, 1945, issue of The Courier; and in the Sept. 4, 1948, edition of the paper, Cohen reported that two members of the Negro National League’s New York Cubans – pitcher Jose Santiago and future National Baseball of Famer Oresto Minoso, later, of course dubbed Minnie – had been sold to the Cleveland Indians for an undisclosed amount.

Finally, Cohen contributed a lengthy feature article to Spot Magazine in July 1942, about none other than legendary Josh Gibson. In the piece, Cohen detailed Gibson’s career trajectory, achievements and impacts on Black baseball. Because Josh’s exploits have already been well chronicled elsewhere and, as we know, quite numerous, I won’t refer to Cohen’s reporting on that subject. I’ll just wrap up this post with a hefty quote from the first section of Cohen’s article, and I think Cohen’s words will speak for themselves:

“When then isn’t [Gibson] in the National or American League, catching for the World Champion Yankees, the Dodgers or one of the other pennant contenders? An unwritten law of the majors bans from its fields all colored – a prissy prohibition that is out of line with big time baseball’s reputation for sportsmanship. Thousands of fans, both famous and humble, have strenuously objected to Jim Crowism on the diamond, pointing out that it is ironical to find discrimination in America’s national game, that the big leagues deprive themselves of much valuable talent, and that it’s not quite logical for a sport that had a Black Sox scandal to exclude representatives of a race that boasts such outstanding sportsmen as Joe Louis, Henry Armstrong and Jesse Owens. Be that as it may and many another colored star can’t play with white boys.

“After 12 years in colored baseball, and at the age of 30, Gibson has compiled so many records with his hickory stick that it is doubtful if the great Babe himself did any better.”