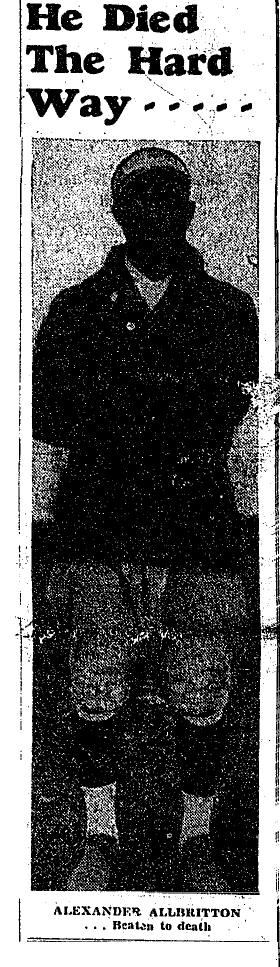

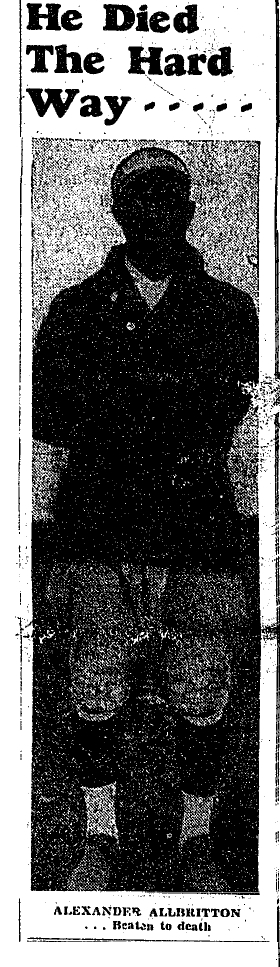

To continue the Alexander Albritton story, I wanted to write a little about the event that makes his saga as intriguing as it is – the particularly tragic way he died.

His violent, horrific death at Byberry State Hospital in Philadelphia is, quite understandably, a discomforting, even disturbing subject to broach, let alone examine in detail. To do so, truthfully speaking, can feel particularly macabre or morbid.

But maybe Albritton’s death – including the at times graphic details – must be examined because it embodies some of the uncomfortable realities about life in decades and centuries past.

In Alex’s case, we find a severely mentally ill Black man killed during a violent altercation with a white hospital orderly who was ostensibly acting as an authority figure.

In Albritton’s situation, we have a death with questionable, unclear circumstances of a patient at a now-shuttered psychiatric institution that had a notorious reputation for deplorable conditions, overcrowding and abusive treatment of helpless, captive, suffering patients – a reality that, sadly, was endemic to mental hospitals in times past.

That, to me, is why the details of the death of Alexander Albritton, a major-league pitcher who played with and against some of the greatest baseball players and managers of all time, are worth examining – and questioning.

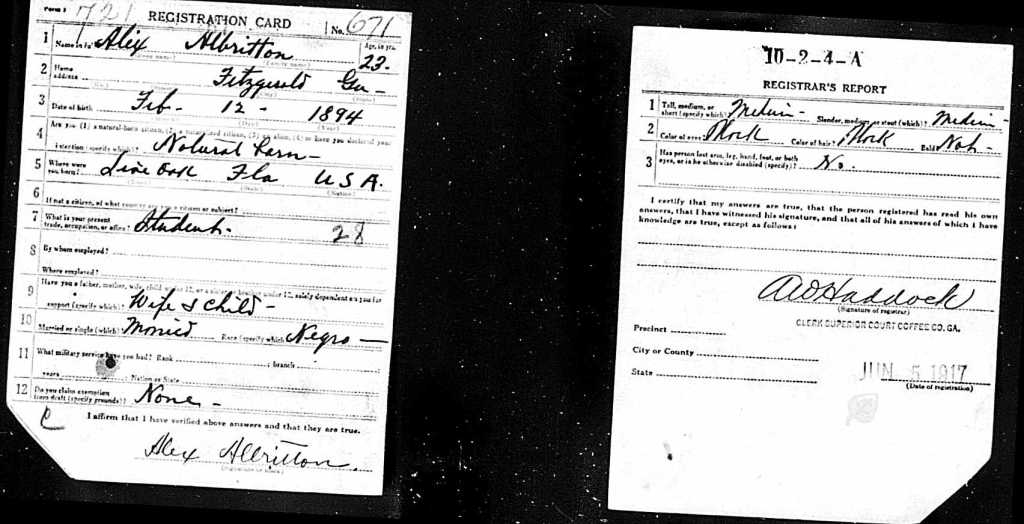

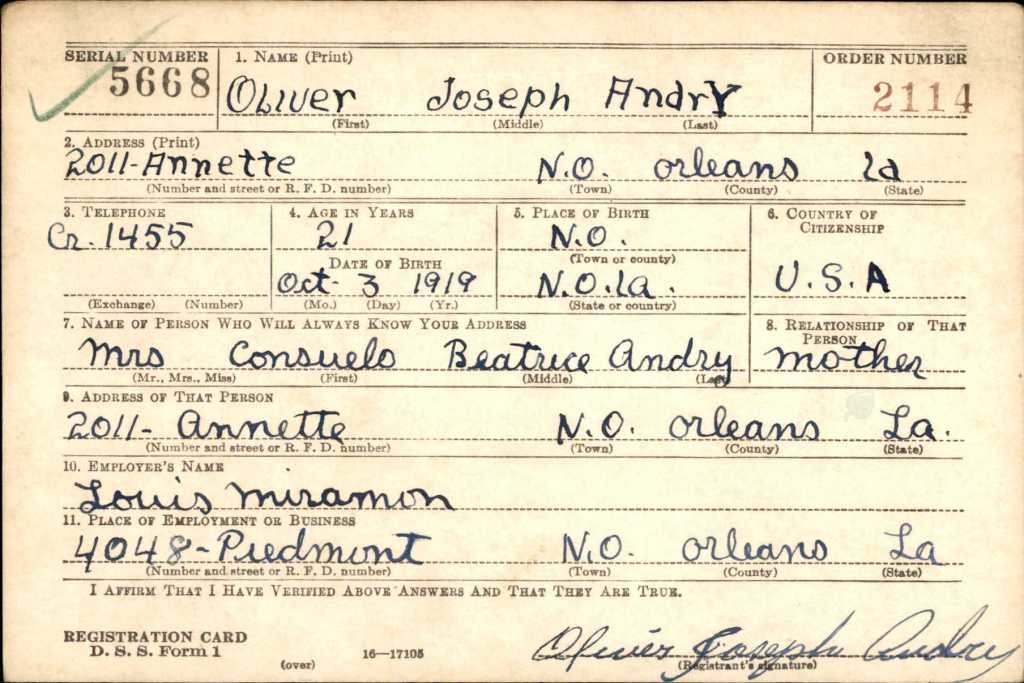

According to the Feb. 8, 1940, issue of the Philadelphia Tribune, Albritton’s wife, Marie, said he had been hospitalized “following a nervous breakdown” in January 1939, a little more than a year before his death in Byberry on Feb. 3, 1940, just nine days short of his Feb. 12 birthday. (The year of his birth varies; his World War I draft card gives it as 1894, while the 1900 Census states 1892. The 1910 Census indicates 1893, the 1930 Census asserts 1896, and his death certificate states that he was 42 when he died, indicating he was born in 1897.)

The Tribune article reported that, according to Byberry officials, the 160-pound Albritton, who had been committed to the hospital’s violent ward, “had delusions that he possessed much money, that he was the father of President Roosevelt [I’m assuming FDR, who was president at the time], and that God was always speaking to him …”.

The Feb. 10, edition of the Pittsburgh Courier asserts that Albritton “was found [on Feb. 3] sitting upright on a stool, stone dead, hastened to eternity by his injuries, at Byberry … .”

The paper further stated that he was found as such at 2 p.m. by an attendant, and that the superintendent of the hospital, Dr. H.C. Woolley, said that Byberry physicians had examined Albritton previously, right after learning of the patient’s Feb. 1 altercation with Frank Weinand, a white orderly who reportedly outweighed the former baseball player by 70 pounds.

That initial exam “found nothing wrong” with Albritton, and at an ensuing exam, at 1 p.m. on Feb. 3, “Albritton was stripped for a routine examination and still nothing was found wrong with him … .”

The Philadelphia Tribune, meanwhile, reported that when examined by staff right after the fight, Albritton “made no complaint. He had a few bruises but when [hospital staff] applied a cold pack to quiet his nerves, they were unable to obtain a coherent story from him.”

The paper said hospital officials reported that, apparently on Feb. 3, Albritton “again became violent. Wrapped in sheets to quiet him this time, he calmed down. Two hours later he was found dead.”

It seems, shall we say, incongruous that a 42-year-old patient who had, according to one report in The Philadelphia Inquirer (a mainstream daily paper) been “beat into submission” by a 31-year-old man who outweighed the victim by roughly 70 pounds, could be deemed injury-free, but then found dead, unattended, two days later.

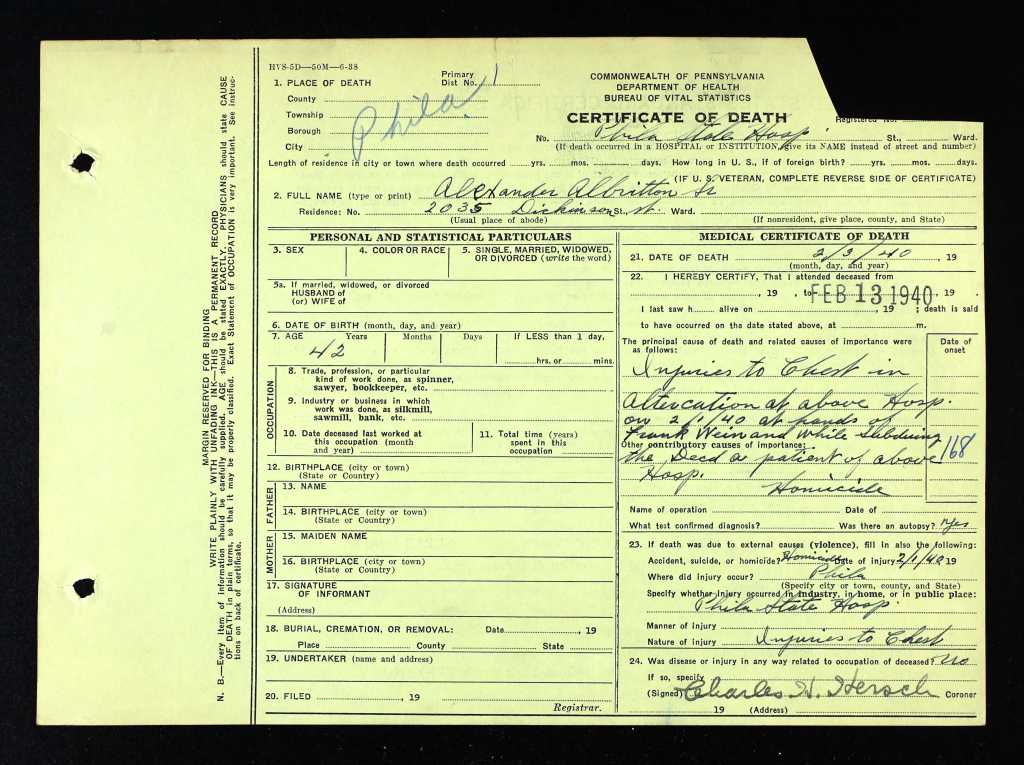

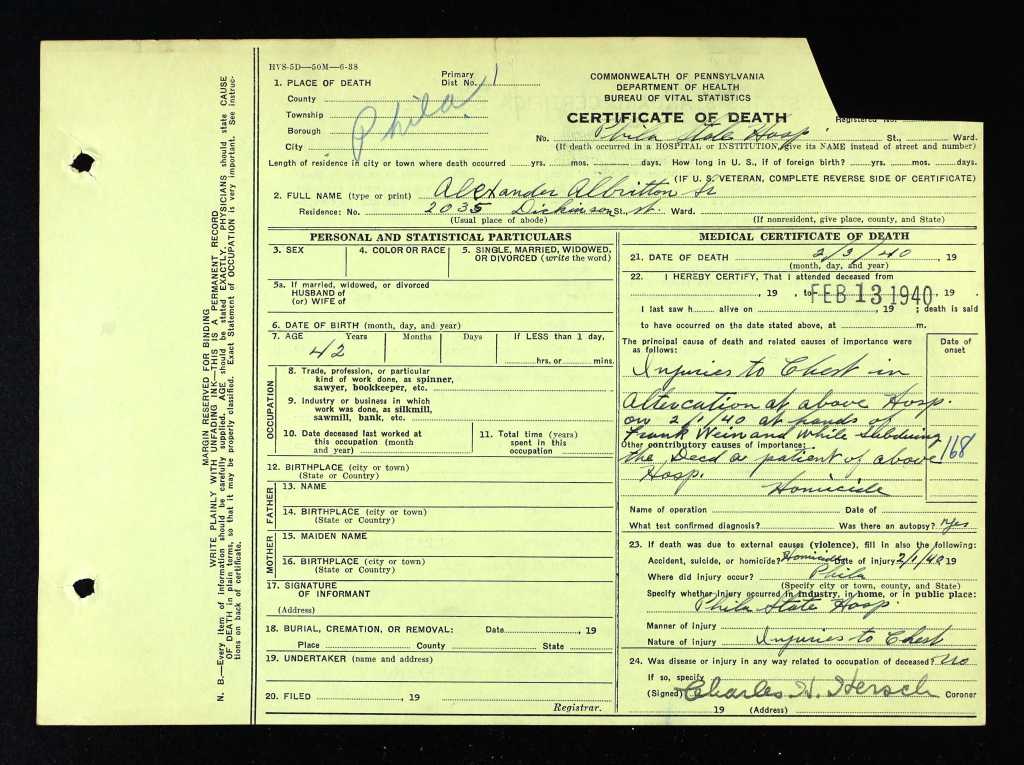

That reflective dissonance could be because the extent of Albritton’s actual injuries remain a little unclear, just as they were 85-plus years ago. His death certificate states that he died from “[i]njuries to chest in altercation at above hosp. on 2/1/40 at hands of Frank Weinand while subduing the dec’d a patient of above hospital.”

The ultimate determination by coroner Charles A. Hersch, according to the death certificate? “Homicide.”

Still, that vague summary is just that – a summary. But what, exactly, were the “injuries to chest”?

The Inquirer reported that a post-mortem exam of Albritton found four broken ribs, a punctured lung, and contusions on the body and arms. The Baltimore Afro-American, though, quoted a police report that asserted Albritton “suffered broken right and left ribs, punctures of the lung, and lacerations of the lip and eyelids,” while The Philadelphia Tribune stated that the former ballplayer had been “[t]he victim of a severe beating the results of which were five broken ribs, a punctured lung and lacerated lip.”

The severity of the injuries inflicted upon Albritton by Weinand was so extensive that one police detective was quoted by The Tribune saying, “Allbritton [sic] appeared to be the victim of an unnecessarily savage attack.” The paper then quoted a hospital official responding to the detective’s assertion: “I wouldn’t go so far as to say that, but a man doesn’t get broken ribs easily.”

Which begs the question: What, precisely, did happen between Weinand and Albritton that would have injured the latter so badly that he was found dead two days later?

Again, there’s mainly vagaries. But the basic outline upon which all accounts generally agreed is this:

Weinand had earlier been charged with assigning tasks and chores for Albritton to do, and on Feb. 1, the attendant gave the patient a wooden broom with which to sweep up the ward. Albritton, for whatever reason, didn’t react well to the directive and attacked Weinand with the broom handle, cracking Weinand on the head with the instrument hard enough to cause a contusion severe enough to require several stitches. Weinand then physically subdued Albritton.

That outline leaves a pair of mysteries; One, why exactly did Albritton, as stated in some media reports, “go berserk” and attack Weinand?; and two, precisely what methods or actions did Weinand employ to “subdue” Albritton?

The first question will probably forever remain unanswered. Based on the assertions by hospital staff that Albritton heard voices and had specific delusions of grandeur, he was likely schizophrenic and possibly prone to periodic psychosis. He had also been committed to the facility’s “violent ward.”

However, it must be remembered that the overwhelming majority of people with mental illnesses, even those with severe cases, rarely if ever lash out with violence or threaten or cause physical harm to other people; in fact, they are much more likely to be the victims of violence, including on themselves. Many folks in the public only hear about the isolated, rare cases in which the mentally ill attack other people.

So we shouldn’t necessarily chalk up Albritton’s reaction to Weinand’s order as “crazy people do crazy things.” Just like so many asylums in the U.S. in times past, conditions at Byberry were deplorable, so much so that I imagine that living at the hospital could easily make patients extremely unhappy as it was.

Plus, the Feb. 17, 1940, Afro-American reported that during an earlier visit to the hospital by Albritton’s wife, Alex told her that “he was being ‘picked on’ by ‘someone around here’ and that he was going to ‘get even.’” He didn’t give any names, however, so it’s uncertain whether his bully was, in fact, Weinand.”

Which brings us to the actual fight on the day of Feb. 3, 1940. Investigators with both the Philadelphia police and the hospital attempted to piece together what happened, but unfortunately, they were unable to assemble the entire picture because it lacked the input of one of the two key players – Alexander Albritton himself. However, it would be fair to note that if Albritton had survived, the reliability of his testimony given his psychological conditions might have been somewhat weak.

According to an article in The Philadelphia Inquirer from Feb. 5, 1940, investigators, after initial interviews with Weinand and several WPA workers who were present, laid out what they believed happened.

According to their story, Weinand had handed Albritton “a heavy broom, of the type used to sweep streets” and directed the patient to sweep a cellar way in one of the facility’s violent wards. As Weinand then turned away, Albritton allegedly swung the broom and hit Weinand on the head, causing the orderly to fall to the floor with a gash on his head.

Added The Inquirer: “The broom handle broke and Allbritton [sic] continued to belabor Weinand with the broken portion until the latter regained his feet and grappled with his attacker. Other attendants assisted Weinand in overcoming the deranged man and removed him to the infirmary for treatment to quiet his nerves.”

Weinand was arrested by detectives at his home in the borough of Hulmeville, Bucks County, Pa., on the night of Feb. 3 and appeared before a magistrate the next day. He was charged with homicide and held without bail pending the result of a coroner’s inquest. (Bucks County is adjacent to Philadelphia and considered a large suburb of Philly.)

However, it only took a day for Weinand to be informally but virtually absolved of any wrongdoing in Albritton’s death after three separate reports – by the Coroner’s Office, the PPD and the state police – determined that Weinand used necessary force to subdue Albritton. Weinand was released from jail a little while later.

While the white press reacted to the clearing of guilt for Weinand with much of the typical, passive credulity regarding the official line that the media of the day usually viewed matters of race, the country’s African-American media was, shall we say, significantly less willing to swallow the legal absolution of Weinand.

For example, within its Feb. 10, 1940, article about Albritton’s death, The Pittsburgh Courier included a paragraph bulletin of breaking news, and the paper didn’t mince words:

“Investigators Tuesday applied the whitewash on Byberry for the death by beating of Alexander Albritton, former star Hilldale pitcher. In absolving physicians and attaches of blame in the fatal beating, the implication was that [g]uard Frank Wienand [sic] was justified in cracking Albritton’s ribs, puncturing his lung and administering to him a savage beating.”

“Investigators Tuesday applied the whitewash on Byberry for the death by beating of Alexander Albritton, former star Hilldale pitcher. In absolving physicians and attaches of blame in the fatal beating, the implication was that [g]uard Frank Wienand [sic] was justified in cracking Albritton’s ribs, puncturing his lung and administering to him a savage beating.”

Pittsburgh Courier, Feb. 10, 1940

The Philadelphia Tribune interviewed three local Black doctors for the paper’s Feb. 8, 1940, article on the incident, and all three expressed astonishment that Weinand could have inflicted as much injury to Albritton as he did.

“Why, a person would practically have to stomp on a man’s chest to break five ribs,” one physician said, while another asserted that “[t]o beat a man to death requires great strength. Ribs aren’t easily broken with fists. I would say that some heavy instrument was used in this case.”

Even with all this media reportage, I couldn’t pin down precisely how Weinand’s case proceeded through the criminal justice system. Following the news of the investigations informally clearing him, he seems to have stayed in jail pending a coroner’s inquest.

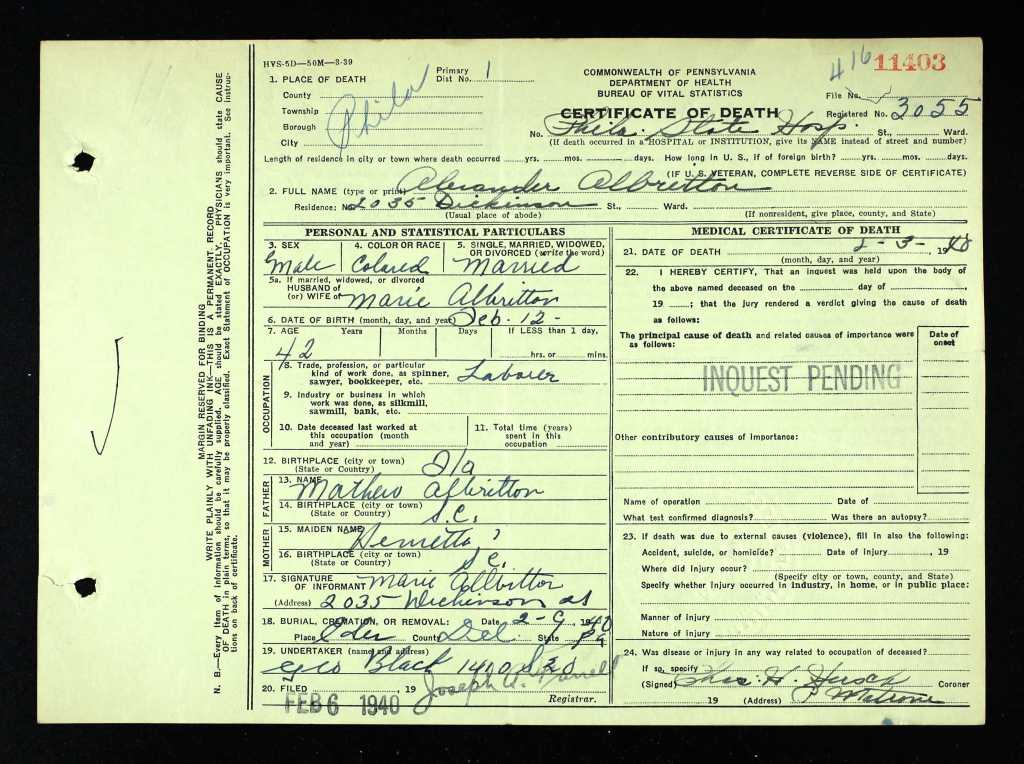

On Feb. 6, three days after Alex’s death, Coroner Charles Hersch issued an initial death certificate for Albritton that left the cause of death section simply stamped “inquest pending.” However, I couldn’t find any news coverage of the results of that inquest or even when it took place.

Hersch did eventually file a second death certificate, but it contained several inconsistencies and incomplete information. The cause of death was listed as “homicide” as a result of severe chest injuries “at the hands of Frank Weinand while subduing the dec’d [deceased].”

However, there’s no filing date given, just a death date of Feb. 3, 1940, which is consistent with the first death certificate. In addition, the date of Feb. 13, 1940, is stamped in the section for when a doctor attended to Albritton’s death and when the doctor last saw Alexander alive. (In another deviation from the first death certificate, the second document is supposedly signed again by Hersch, but the handwriting is blatantly different than on the original certificate.)

That means the inquest might have happened on Feb. 13, but again, I’ve found no confirmation for that inference. Moreover, an article in the Saturday, Feb. 10 Philadelphia Inquirer has the charge downgraded to manslaughter, with Weinand still being held in jail without bail.

But that Inquirer article also reports, though, that Weinand’s attorney had obtained a writ of habeas corpus, and that a court hearing would be held concerning the writ the following Tuesday, Feb. 13, at which time Weinand’s attorney “will seek to show at the hearing that Weinand struck the patient in self-defense.”

Then, on Feb. 21, 1940, according to news reports, was released from jail under $1,000 bail as a result of the habeas corpus hearing, and that Weinand’s trial had been scheduled for some time in April.

But that’s all I could glean from newspaper reports. Police, jail and court archives from Philadelphia in 1940 might be able to clear things up, but at the moment that doesn’t appear possible online, and I can’t travel to Philly to look up the information in person – if those records still exist at all.

It should be noted that in the fall of 1940, news reports show that Weinand had been issued a questionnaire by the draft board for possible military service. The newspaper listings state that Weinand was living in the borough of Bristol in Bucks County.

That seems to indicate that he wasn’t in prison at that time, which would mean he was either legally exonerated of the crime or that he was found guilty of at least one but given a relatively light sentence. Again, I’m not sure on this matter.***

Meanwhile, Alex Albritton’s 37-year-old widow, Marie (nee Brooks), reportedly retained attorney Raymond Pace Alexander to advocate for further investigation into her slain husband’s death; however, how that lobbying for more investigation turned out, I’m not sure. Marie seems to have then at some point moved to New Jersey, where she died in the city of East Orange in 1975.

(Pace Alexander spent a lengthy career fighting for Civil Rights, particularly advocating for public or commercial entities to stop excluding or barring people of color. He later became a Philadelphia city councilman and later was the first Black judge on the city’s Common Pleas Court, eventually becoming the court’s senior judge before dying in 1975.)