Worcester Spy, May 18, 1895

I’ve talked before about how I have family roots in central Maine, way up in the woods, and I’ve written a few Maine-centric posts on Home Plate Don’t Move, such as here.

However, in addition to a natural affinity for all things Pine Tree State, I also enjoy dipping into Native-American history when I can (including when that history intersects with the Negro Leagues, such as here and here), and the combination of those two interests led me to recently purchase and read Brian McDonald’s book, “Indian Summer,” a biography of Maine native Louis Sockalexis, the first acknowledged Native-American to play in major league baseball.

(Research has recently found evidence that the honor of first American Indian to play in the majors was Jim Toy, a Pennsylvania native who competed for a couple major league teams between 1887 and 1890, but who apparently “passed” as white and as such wasn’t recognized as a Native-American during his career).

Sockalexis was a member of the Penobscot tribe, a relatively small group located in Old Town, Maine, a small island community nestled between two rivers and located just north of Orono, which is the home of the University of Maine.

Sock’s astonishingly quick ascent to baseball stardom was followed by an equally precipitous — and quite tragic — fall. His raw athletic talent was prodigious, especially when he poured it into America’s still-growing national pastime of baseball. He roamed the outfield with a quickness and natural instinct that seemed to preternaturally guide him to almost any ball lofted his way. He also possessed a cannon of an arm and a savvy, heady, daring fleet-footedness on the basepaths.

He was also a dangerous hitter, capable of tremendous, slashing power, especially once he mastered hitting a curveball.

Boston Globe, May 5, 1895

In 1897, at just 25 years old, Sockalexis earned a spot on the roster of Cleveland’s National League club, nominally dubbed the Spiders. He had a blistering first half of the season — at bat, on the bases and in the field — that both tabbed him for eventual superstardom and caused the Spiders’ attendance to rocket.

However, by the end of July 1897, Sock’s quickly worsening alcoholism — along with an untreated broken ankle — hastened a swift decline first into mediocrity, then into oblivion. He received less and less playing time as the summer came to a conclusion.

The following season continued the swift decrease Sockalexis’ playing time, and while he was able to maintain sobriety for some stretches, his frequent alcohol benders and his bum ankle ensured his place on the bench.

The 1899 season saw the end of both the Spiders and of Louis Sockalexis’ major-league career. He subsequently hoboed around the minor leagues of New England, signing contracts when he could but invariably blowing each chance he had at a comeback because of his physical deterioration. By the end of 1903 he was out of organized baseball for good, just six years after rocketing onto the national hardball scene as a can’t-miss prodigy.

On Christmas Eve 1913, Louis Sockalexis died of a heart attack while working on logging crew at just 42 years old. He thus joined the seemingly endless parade of “what might have been” tales throughout baseball history — which, in many ways, mirrored the fates of hundreds of Negro League and blackball players who never got the chance to become the stars they could have been in organized baseball.

And just like those black ball stars, Louis faced the same kind of racism and hostility that African-American players have faced for a century and a half of baseball. While the bigotry Sockalexis encountered might not have reached the same oppressive level of spite and intensity experienced by black players, the prejudice certainly contributed to the withering, alcohol-fueled despair that destroyed his promising career.

Sock’s tale has been told multiple times in book form, and McDonald’s biography is quite good, if a little skimpy on details of his youth with the Penobscots and his later years after his baseball career ended.

Why do I bring this up in a blog about the Negro Leagues? Because MacDonald’s book also talks about Sockalexis’ pre-professional college career, first at Holy Cross in Worcester, Mass., then briefly at Notre Dame in Indiana.

The campus of Holy Cross

The time Sockalexis spent studying at and playing baseball for Holy Cross in 1895 and ’96 (he also was a running back on the school’s football team and ran track) was extremely productive, joyful and hopeful, an experience he used as a launchpad to organized baseball and the major leagues.

At the time there probably weren’t enough institutions of higher learning that offered varsity baseball, if they did any sports, so collegiate clubs had to fill out their spring and early summer schedules by playing semi-pro, town and barnstorming teams.

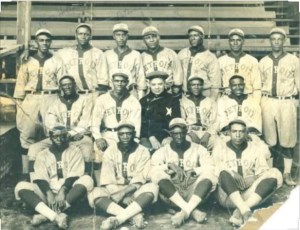

For Holy Cross, those semi-pro foes came from all across the Northeast and, in 1895, they included none other than the Cuban Giants, the first all-black professional baseball team (with an ensuing lack of clarity, as you’ll see in a few paragraphs down).

The Cuban Giants were formed in 1885 with wait staff at the Babylon Argyle Hotel on Long Island, and they instantly became the class of “colored” baseball by touring constantly. There were no stable colored leagues at the time, so the Cubans — there were no actual Cuban men on the team, with the name being basically a marketing technique to appeal to a broader (read: white) fan base.

Adding to the attraction was the Giants’ playful yet tomfoolery that engaged stadium crowds with colorful gabbing, very enthusiastic coaching and the type of ball hawking and catching skills that many white baseball fans had never seen.

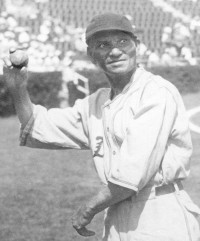

Early on the Cuban Giants’ roster was studded with black baseball stars, including future Hall of Famers Sol White and Frank Grant, as well as other legends like Clarence “Waxey” Williams, George Williams and John “Pat” Patterson.

Sol White

The Giants enjoyed their first full season in 1885, and by the time they played the Holy Cross squad nearly a decade later, the African-American aggregation were well known and highly sought after as opponents for towns, city’s and other teams throughout the country and especially in the Northeast.

The clashes between the two teams made for a fascinating anecdote in McDonald’s book on Sockalexis — the first black professional baseball team squaring off against the man who would become the first acknowledged Native-American player in the major leagues.

Holy Cross and the Cuban Giants first encountered each other during the 1895 season on May 18 at Worcester, with the African Americans clubbing the Crusaders, 9-1, with Sockalexis going 1-for-3 and scoring his team’s only run. He also swiped a base. Grant went 3-for-5, stole a base and scored three runs for the Cubans, while Robinson (I’m not sure of his first name) got the win in the mound.

Here’s how the Boston Globe described the G-men’s win:

“The Cuban Giants created quite a lot of fun for the spectators by their lively coaching. They played fast ball all the time, taking every advantage of their opponents’ misplays.”

Waxey Williams, added the Globe, “supported [Robinson] in good shape besides amusing the crowd in the grand stand by his catchy remarks.”

The Cubans came back to Worcester for a return engagement on May 28, when the result was the complete opposite of the first kerfuffle — the Crusaders this time clobbered the Cubans, 12-5.

On the mound, Holy Cross pitcher John Pappalau stymied the Giants hitters, scattering nine (or 10, depending on the source) hits for two earned runs and 11 K’s.

The Giants also played a sloppy game, making a whopping seven errors and allowing eight unearned runs. Bill Selden started the contest on the mound for the G-men, but he was quickly yanked for Robinson, who didn’t fare much better.

Sockalexis went 2-for-4 with a double, while Grant again led the Cubans by going 3-for-4 and a run scored. Waxey Williams smashed a home run as well.

Clarence “Waxey” Williams

(Pappalau ended up joining Sockalexis on the Spiders’ 1897 roster, bagging a single season in the majors.)

But here’s the weird part — McDonald, while correctly stating that Holy Cross played the Giants in 1895, In his book, he refers to an undated game with a score I couldn’t confirm. He wrote:

“The school also took advantage of baseball’s popularity by scheduling games outside the college ranks. In 1895, Holy Cross played the vaunted Cuban Giants. Originally a team made up of black porters to entertain guests at a posh Long Island hotel, the Giants had become a traveling sensation. There were no Cubans on the team, but the name was affixed to the club as a way to side-step the stigma then surrounding black ballplayers. The Cuban Giants were led by Ulysses F. ‘Frank’ Grant, one of the premier black players of the nineteenth century. Though the contest was game, the Holy Cross nine lost to the Giants, 6-5.”

Moving past that idiosyncrasy and jumping along further, it’s interesting to note that the regional New England press covered the exploits of both Holy Cross and the Cuban Giants throughout that season, so much so that, in addition to the two teams’ games against each other, they sometimes appeared on the same page of newspaper coverage.

The May 3 edition of the Boston Globe reported Holy Cross’ loss to Brown University, the Crusaders’ first defeat of the spring. Just six columns inches below that, the Globe included a brief about a Giants’ triumph over the University of Vermont (more on the UVM Catamounts later).

A little under two weeks after that, the Globe reported on one of the Cuban Giants’ triumphs over Wesleyan, and two short box scores below that, the paper announced an impending Holy Cross contest against Hahvahd. Then, on June 2, the Globe noted the Crusaders’ loss to Yale, exactly adjacent to a short report on another Cubans victory over UVM.

Beyond their games against the Crusaders, the Cuban Giants’ spring through fall 1895 schedule trekked all across the Northeast, especially New England, taking on all comers. While Sockalexis was burning up the basepaths for Holy Cross, the Giants sauntered from Connecticut to Rhode Island to Massachusetts to Vermont that season. The Cubans also ventured as far south as Maryland and west into Pennsylvania and New York.

Stated the Philadelphia Times in April 1895 about the Cubans’ tireless travels:

“The Cuban Giants, the colored club, which is now touring the eastern part of this State, is a well managed organization, and it still includes almost the same players that it had ten years ago. The manager is a white man [most likely owner John M. Bright] who knows a thing or two about arranging dates. Although his club is not in any organization [league] he has 125 games booked for the season. His players are reasonable in their demands for salary, and do not want the earth while they are having a good time on the road.”

Such commentary reflects a public image of the team in which the traveling African-American players hard-working and dedicated but also are not to “uppity” or brash (as well as “controlled” by a white man), a combination that made the Giants an appealing opponent for mostly white communities.

Other media representatives approached the Cuban Giants with bemusement and curiosity. Take, for example, the July 22, 1895, Boston Journal, which employed either ignorance or snark (or both, it’s hard to tell) when discussing the team with a reference to global affairs:

“Of what stuff are these ‘Cuban Giants’ made, that they spend their time on the ball field when their country needs their help so sorely?”

Most likely this referred to the Cuban War of Independence from Spain, a conflict that began in 1895 and wasn’t completely resolved until after the Spanish-American War in 1898. Of course, the Cuban Giants weren’t actually Cuban; the team was given the name as essentially a marketing tool that portrayed the players as foreigners, which provided them an air of exoticism and a false image that they were non-threatening foreigners, a mirage that placed the white community more at ease.

So the Journal was either being ignorant, or the writer tried to employ satire to riff on the team’s exploits.

Other communities, though, eschewed such subtlety when hailing the impending arrival of the Giants to their midst, instead employing flippancy at best and bigoted derision at worst. The Mount Carmel (Pa.) Item announced the club’s approach to town in May 1895:

“The Cuban Giants will be here next Thursday to do battle with the Reliance. The ‘n*****s [my edit] are a set of hustlers and will put up a good game under all circumstances as they have done heretofore. Everybody should turn out and hear those Cubans coach.”

About a week later the Item doubled down on its tone:

“The Reliance and Cuban Giants are playing ball at the National park this afternoon, and quite a large crowd from the Gap are listening to the ‘n**s’ coaching.”

I gotta admit it’s a strange day when a town newspaper is so casually racist that it abbreviates the n-word as a method of advertisement.

Now, perhaps a valid question to ask before we proceed concerns the quality of the 1895 Cuban Giants. Were they as good as they were a decade earlier when they formed? Had the club sustained excellence and continued to be one of the most important baseball teams in the scene in the years leading up to the turn of the century?

My friend and colleague James Brunson, who recently published a magnum opus on 19th-century African-American baseball, offered a few thoughts.

“The 1895 Cuban Giants team was good enough,” James offered. “Good enough to split into two clubs in 1896; one being the Cuban-X Giants. I think the Cuban Giants traveled to Chicago that year as well, and played white and black clubs.”

Had the Cubans quality of play dropped off?

“No sir,” James said. “They were still pretty good.”

Having said that, and using the G-men’s clashes with Louis Sockalexis-led Holy Cross as a jumping off point, it’s fascinating to delve into the Cuban Giants other exploits in 1895 as a way of giving context to those encounters with the Crusaders. It also provides a peak into the life of a pre-1900 professional barnstorming “colored” team, an existence that was both thrillingly eclectic and exhaustingly workaday.

Cuban Giants, circa 1895

For many of the Cubans’ opponents, their encounters with the legendary African-American aggregation provided one of the highlights of the baseball season — and it big day at the gate. Games with the Giants were highly sought-after and, frequently, quite financially lucrative.

Often, smaller cities and towns frequently sought out the Cubans as visitors for games against local aggregations, especially when the town was celebrating a big event or having a fair of some sort. The highly touted Giants guaranteed a big attendance at these shindigs, which meant a bigger gate and more jubilant festival.

In June 1895, for example, the town of Brandon, Vt., solicited the attendance of the Cuban Giants at the town fair, scheduled for late September. The Brandon Union newspaper explained why the town pined for a stop from the blackball stars:

“It is expected that the fair as a whole will eclipse the effort of last year and plans are already being formulated and attractions secured for the edification of the public. The athletic committee were [sic] instructed to correspond with the ‘Cuban Giants’ base ball team for the purpose of ascertaining their terms, with a view, if reasonable, to secure their appearance with some other crack ball team as opponents, during one day of the fair.”

But in addition to quirky one-offs in tiny towns across the Northeast, the Cuban Giants also developed regular and heated rivalries with several opponents, including a foe or foes in Hartford (perhaps the Hartford Bluebirds of the Connecticut State League); clubs in Hagerstown, Md.; Newport, R.I. (these guys pop up a little later in this blog post); and Orange, N.J.

Instead of recounting the rest of Cuban Giants’ 1895 schedule in agonizing (for the reader) detail, I’ll touch on a few highlights I found intriguing:

— In June that summer, the club nipped the town team in Woonsocket, R.I., 8-7. No special anecdote here. I just like saying “Woonsocket.” Woonsocket. Goonrocket. Toondocket. Toadthewetsprocket. Now is the time on Sprockets when we dance.

— In late March, the G-men defeated a team from Lakewood High School of N.J., 8-5, showing that the Cubans were truly willing to take on all comers, even high school kids.

— The Giants routinely squared off against collegiate squads; aside from Holy Cross, the team of African American combatants played the University of Vermont (whom I’ll discuss in detail later), Wesleyan University and the blue bloods of Dartmouth, whom the Cubans clobbered, 17-8.

Dartmouth University baseball team, 1895 (photo from Dartmouth Library digital archives)

A resulting brief in the Boston Post reporting on the Cuban Giants’ triumph over the Ivy Leaguers of Hanover, N.H., in many ways encapsulates the team’s impact on any given community they visited — for many whites, watching the Giants display their talents was an experience both astonishing and peculiar. Stated the Post.

“The Cuban Giants won very easily from Dartmouth this afternoon, scoring 17 to 8. Each side wielded the stick vigorously, but the team work of the dusky ball tossers was so much better than that of the collegians that the result was never in doubt, and the exhibition was interesting chiefly on account of its novelty.”

One of the few repeat opponents that seemed to turn the tables on the Giants was the Fall River Indians of Massachusetts. In April 1895, the squads split a two-game series, then in September the Indians swept a pair of contests by a combined tally of 34-9.

Upon discovering these reports, my first thought wasn’t the athleticism, it was the macabre. Just three years earlier, Fall River was rocked by the grisly murder of Andrew and Abby Borden in their own home by an ax-wielding assailant. A year after that, Lizzie Borden, Andrew’s daughter and Abby’s step daughter, was infamously acquitted of the murders, which as a result remain officially unsolved to this day. The surrounding media scrutiny and public sensationalism trained the eyes of the whole world on Fall River, and even today the murders and ensuing trial remain in the public consciousness.

So, being a major fan of horror movies and Edgar Allan Poe (but not an enthusiast for H.P. Lovercraft, who, despite his brilliance, was still a racist, anti-semitic jerk), the mention of Fall River automatically piques my interest. However, the Fall River baseball team will also come up again a little later in this post.

Boston Post, April 20, 1895

While we’re on the subject of Massamachusetts … the 1895 Cuban Giants became a familiar face in Western Mass as well; in July in Orange, Mass., for example, the Giants topped the Central Parks, 10-6.

Why do I have a particular interest in 1895 baseball games in Western Massachusetts? Because, you see, for two years in the late 1990s, I lived in the region, working for the weekly Holyoke Sun newspaper in Holyoke, a small city adjacent to Springfield, the largest city in the region.

Holyoke and Springfield help form the Pioneer Valley area, a region that runs along the north-south Connecticut River from the Connecticut state line up to Vermont.

Anchored by Springfield (the home of the Basketball Hall of Fame) on the Mass-Connecticut line, the Pioneer Valley also includes what’s colloquially known as the “Five College Consortium” — the University of Massachusetts-Amherst, Hampshire College, Mount Holyoke College, Amherst College and Smith College. The last four are private, liberal-arts institutions, and Smith and Mount Holyoke are women’s colleges. UMass-Amherst is the state’s flagship public university. (My brother earned his bachelor’s from there.) Also, confusingly, Mount Holyoke is not located in the city of Holyoke; it’s across the river in South Hadley.

(Also, let’s get one thing straight — contrary to popular theorizing, the Five College Consortium are not the basis for the characters on “Scooby-Doo.” According to the legend, Daphne is Mount Holyoke, Velma is Smith, Fred is Amherst, Shaggy is Hampshire and Scooby is UMass. But numerous people involved with the classic cartoon have asserted that the rumor isn’t true.)

Anyway, so I lived in Western Mass for a couple years, and it was a remarkable, emotional and bizarre time in my life. West of the Pioneer Valley run the Berkshire Mountains, a range in which is nestled a bunch of small, quaint, historic towns, such as Great Barrington, North Adams and Stockbridge.

The Berkshires could be viewed as the confluence of the Appalachian Mountains from the south and the Green Mountains from the north, and the region has become known as a resort area that attracts tourists visiting the forested highlands and enjoying the region’s rich arts, music and culture scene.

Baseball, especially in the sport’s beginnings, thrived in the Berkshires, as Major League Baseball historian John Thorn details in his revelatory book, “Baseball in the Garden of Eden.” The earliest known written reference to “base ball” occurred in Pittsfield, Mass., the large town at the northern end of the Berkshires, in a 1791 bylaw aimed at stopping those blasted kids from busting windows while playing this newfangled pastime.

Baseball teams of varying size, level and organizational status dotted the Berkshires and Western Mass throughout the 19th century, including the 1890s, when the Cuban Giants were thriving by traversing the country and taking on town teams in geographic nooks and crannies.

In 1895, the Cubans travels brought them frequently to Western Mass and the Berkshires for a few reasons, not the least of which was that Giants star and eventual Baseball Hall of Famer Frank Grant was from Pittsfield, where he began his baseball career. Grant also frequently returned home to visit family in Pittsfield.

North Adams Transcript, Nov. 6, 1895

Another reason for the G-Men’s frequent presence in Western Mass in 1895 was the formation of, in August of that year, the Stanleys, a semipro club based in Pittsfield that took on the Cubans several times in late summer.

(With a dive into the research only a bit deeper than the tertiary level, it’s hard to pin down completely where the Stanleys were based because there were other towns with other teams, likely most semipro or club, in the Berkshires area, including Great Barrington and North Adams. Some of these other aggregations played the Giants as well, all of which at the very least that the region remained a hot spot for the burgeoning national pastime.)

The Cuban Giants’ meetings with the Stanleys were fairly well covered by the local press, such as The Berkshire County Eagle of Pittsfield, The Pittsfield Sun and The North Adams Transcript. The clashes even got a paragraph in the Springfield Republican now and again.

The day before what was apparently the teams’ first engagement, the Eagle noted, “Tomorrow’s game with the Cuban Giants will be one of the most interesting of the season as the visitors are a very strong team. Their coaching is one of the features.”

And a later issue of the paper that “[T]he Cuban Giants are one of the leading attractions of the country and by far the best traveling team.” Both assertions reflect how highly prized a date with the Giants was, and how much the “colored” team got people a-talkin’ about the Cubans’ arrival.

Let’s highlight what was by all accounts the finest Cubans-Stanleys game — the one on Aug. 13 of the year in question that boiled down to a nailbiter of a pitching duel that ended in a hard-fought, 1-0 triumph by the visitors after the G-men’s John Nelson got the W over the Stanleys’ John Pappalau.

Berkshire County Eagle, Sept. 4, 1895

(Pause for another entry in the “well ain’t that a coincidence” file. Pappalau came to the Stanleys after attending and pitching for Holy Cross on the same collegiate roster as … Louis Sockalexis! Moreover, Pappalau even briefly joined his college mate with the Spiders in 1897, when Pappalau pitched in two games for the Cleveland MLB club.)

The Aug. 13 game between the blackball legends and the Stanleys not only reflected how the Giants frequently brought with them some stellar, thrilling baseball, but the coverage of the clash — especially in the Berkshire Eagle — reflected the tremendous popularity of the Cubans each summer.

Unlike the few previously mentioned newspaper articles that used derogatory words and exhibited a flippancy and ignorance about the Giants, the Eagle’s Aug. 14 issue was extremely flattering:

“The kind of baseball played at Waconah park cannot but help in promoting interest in the game in this county and although the home team was beaten, hardly a person left the grounds but what were satisfied they had more than received their money’s worth in seeing one of the sharpest games of the season. The Stanleys had as their opponents the celebrated Cuban Giants and although outplayed in the field, the home team made a credible showing.

“A team that is able to hold the Cubans down to one run is able to hold its own with any semi-professional team in the country. …

“The visitors, who by the way are among the most gentlemanly set of players seen here this season, put up a game in the field that could not be beaten. They covered a large amount of territory and upheld the great reputation they have throughout the country. There is no let up in their game which keeps up the interest from the beginning to the end.”

The article then added:

“The game put up by the visitors would make any team a big drawing card. Their coaching is a feature and they are in the game all the time.”

As an aside that tenuously connects Louis Sockalexis with my personal history, Sock — who spent several of his post-MLB career as a baseball vagabond, bouncing and careening and hoboing through the Northeast, playing for teams of all levels and invariably getting kicked off each one, usually because of his alcoholism — himself made a stop or two in Holyoke, where I lived and worked for two years. Unfortunately, at least one of those visits did not exactly go well — in August 1900, he was arrested for vagrancy at spent 30 days in the Holyoke clink. In the ensuing years there were reports that Sockalexis was seeking a spot on a team in Holyoke, but by then he was physically wrecked and psychologically crushed.

Dayton (Ohio) Herald, Aug. 23, 1900

Now to bring back two of the previously mentioned Giants opponents, Fall River and Newport, as well as contemplate a common phenomenon around this time — the emergence, operation and often quick disintegration of leagues of all sizes and levels

It honestly can get very confusing. So there was there was minor-league New England League for decades between the 1880s and 1940s. Apparently teams and franchises came and went, then came and went again. Different cities would rotate in for a few years, then bag their team and league membership.

Over these decades the league changed size, covered an always-amorphous geographic reach, and shifted between minor-league levels. There were a handful of times when it didn’t play, and during World War II it was even a semipro loop. It seems the New England League’s importance soon waned by the time the American League joined the National League as the country’s two major league circuits and as an organizational, hierarchical network of the hundreds of pro baseball teams scattered all over the country — the formation of “Organized Baseball.”

It looks like that in 1895, according to Baseball Reference, the New England League included eight franchises — Augusta, Bangor, Brockton, Fall River, Lewiston, New Bedford, Pawtucket and Portland — but BR doesn’t list any stats, records, standings or championships for the 1895 NEL.

And as far as this blog post goes, I’m not really concerned about that. What’s important to note is three-fold:

One is just the entire baseball landscape that existed in New England in 1895. With the formation of Organized Baseball still a little ways away, teams of all sorts — pro, semipro, college, amateur, touring, barnstorming, from all six states in New England — were all mixed up together is a mild free-for-all.

While a minor-league New England League existed, the professional “farm” system hadn’t really emerged yet in the sport (that would happen in 1901), meaning that every franchise, every club, every town, it seems, could do whatever it wanted — join a league, drop out of a league, not join a league at all, barnstorm — and could play wherever it wanted, outside of any league structure. Teams that were in leagues had their league schedules, but they also played exhibition games, one-off contests against traveling clubs, pre-season contests with college teams, games at county fairs — anything that could bring a decent payday.

This loose system also allowed players — and coaches and managers, for that matter — to hop from region to region, state to state, team to team with chaotic fluidity. The infamous reserve clause, which bound players to their respective teams even after the players’ contracts had expired, was in the process of forming in the 1890s on the major league level, but with the formal minor-league system still a half-dozen years off, baseball teams below the major-league level had free reign, I think.

Which allowed minor-league clubs (as well as collegiate ones) to play the Cuban Giants, including in 1895. But one particular little scheduling quirk that took place that year was something I’ve never really stumbled across before in my research — a spontaneous, late-season “league.” This newfangled circuit kind of filled in for the New England League, which apparently fell apart sometime earlier in the baseball season.

Windham County (Vermont) Reformer, Sep. 13, 1895

And not only did this “quadrangle” circuit sprout up, but one of the four teams in the league was the Cuban Giants. So along with the pro teams from Fall River; New Bedford, Mass.; and Newport, the four-team loop had a trailblazing, barnstorming, African-American aggregation. (As noted earlier, Fall River and New Bedford had been members of the New England League.)

I wasn’t able to delve too deeply into this league — I’m not sure what, exactly, the format and scheduling were, and I don’t know who won the “championship,” if there was any — but the fact that it existed, and that it included the Giants, is pretty fascinating in and of itself.

Unfortunately, from the coverage of this four-team league that I’ve uncovered, it appears the Giants didn’t do all that well in circuit play. They seem to have lost a lot more than they won, including a handful of blowouts. On Sept. 12, 1895, New Bedford bashed the Cubans, 15-3; the Boston Globe reported that “New Bedford knocked the Cuban giants [sic] all over the lot today in the presence of 1200 people.” Then, on Sept. 20, Fall River clobbered — the Globe used the term “annihilated” — the Giants, 20-3.

The Cubans managed to win one or two of these league games, though, including their first victory, on Sept. 16, when they toppled Newport, 10-4.

One final note here … even though I do have strong personal and familial connections to Maine, and even though I started this epic post by pointing out that fact, I couldn’t find any coverage of the Cuban Giants playing in Maine in 1895. That doesn’t mean they didn’t; I just didn’t uncover any such Pine Tree State excursions.

If anyone has any comments, questions or corrections about or for this post, definitely let me know, either by leaving a comment here or emailing me at rwhirty218@yahoo.com.

Aaaaaaaand that tops off my post about the exploits of Holy Cross, Louis Sockalexis and the Cuban Giants in 1895. Well, that’s not true. I hope to do an addendum piece (I promise it won’t be as long as this one!) about two particular aspects of the Cubans’ 1895 outing — a series of games against the University of Vermont, and the Giants’ ventures through Pennsylvania, especially how the black ball club was received in the Keystone State.