Here we have our final post about some of the various databases I have available to tap, and this one takes the conversation about Black baseball and jumps it from Jewish newspapers (the topic of my previous two posts, here and here) to a famous African-American publication, Jet Magazine.

Jet was launched in 1951 as a digest-sized, straightforward, hard-news publication and dubbed itself “The Weekly Negro News Magazine.” (It’s now solely online.) Jet was founded in Chicago by John H. Johnson, who wanted to provide Black Americans the type of positive media coverage and representation that was still sorely lacking in the American culture and social zeitgeist. The publication was owned and operated by Johnson Publishing Company for decades until it was sold in 2016 to the Clear View Group, a private equity firm.

(Jet also had a sister publication, Ebony, that was similarly launched and owned by Johnson and his company. overseen by one company. Founded in 1945, Ebony was originally modeled after Life Magazine, and it gradually evolved into a sleeker news, culture, analysis and commentary magazine than Jet before transitioning, a long with Jet, to online-only within the last decade after purchase by the Clear View Group.)

When first founded, Jet quickly became a vital, bold, fearless publication that unflinchingly covered the Civil Rights Movement and the fight against societal, systemic racism.

Most notably, in the summer of 1955, it covered the funeral of Emmett Till and published a photo of Emmett’s bloated and mutilated body, which was displayed in an open casket by his mother. The image shocked the country and stirred many in the Black community and a few white allies to kickstart the modern Civil Rights Movement.

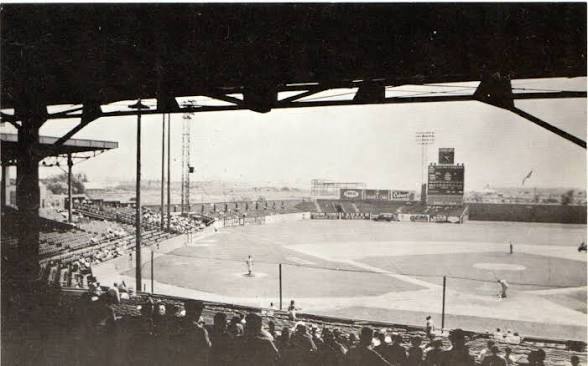

Despite its undeniable impact on news coverage in America, Jet also reported on “lighter” topics, like culture, entertainment and, of course, sports, including baseball. However, by the time Jet was launched in 1951, integration of the major leagues was quickly sapping the Negro Leagues of their talent, recources, financial prospects and vitality within Black America.

As a result, Jet never had a chance to cover the Negro Leagues in their heyday. However, the magazine did report pretty well on these waning years of organized African-American baseball, especially the signing of Black players by major league clubs and the performance of those players in the Major and Minor leagues.

For example, in December 1952, the magazine reported that the American Association’s Minneapolis Millers, at that time the top farm team of the New York Giants, had sold former Negro League star and future Hall of Famer Ray Dandridge to the Sacramento Solons of the Pacific Coast League. (Two years earlier, at the age of 37, Dandridge had been the American Association MVP while playing for the Millers.)

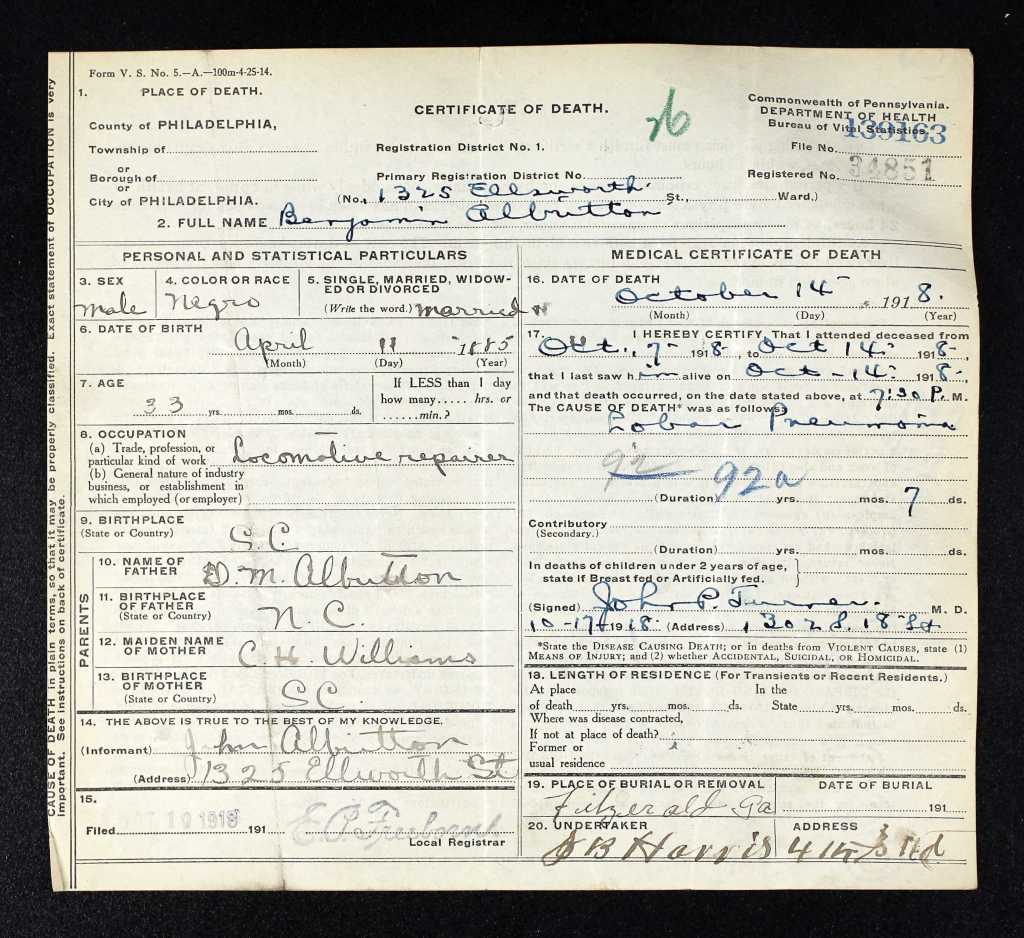

In March 1953, Jet noted that Willard Brown, a former Negro League star outfielder and another future HOFer, had been signed away from the Kansas City Monarchs by the Dallas Eagles of the Double-A Texas League; and in October 1969, the magazine announced the death of Hank Thompson, an ex-Kansas City Monarch who spent several years in the Majors with the St. Louis Browns and New York Giants.

(Coincidentally, in March 1952, the magazine reported a previous signing by the Dallas Eagles – second baseman Ray Neil of the Indianapolis Clowns, who, in inking a deal with the Eagles, became the first African American to do so in the Texas League. Unfortunately, the Dallas club released Neil before the start of the season, and Neil never played in Organized Baseball.)

Some other former Negro Leaguers mentioned in Jet multiple times:

- Fleet-footed Sam Jethroe, who in April 1953 was sent down from the Milwaukee Braves to Toledo of the American Association; and three months later was accused of “lax playing” by Toledo teammates.

- Former Newark Eagle and future Hall of Fame inductee Monte Irvin, who, as noted by Jet, unsuccessfully ran for a seat in the New Jersey Assembly on the Democratic ticket in 1951; spent the 1951-52 off-season from the New York Giants teaching baseball to youth in recreation centers on the New York-New Jersey area; and in 1956 signed with the Chicago Cubs.

- Minnie Minoso, another ex-Negro Leaguer and future Hall of Famer, who copped American League Rookie of the Year honors from the Sporting News in 1951, stated Jet; signed his 1953 contract with the Chicago White Sox for $20,000; and was hospitalized in October 1957, as reported by Jet, for a respiratory infection and elbow trouble.

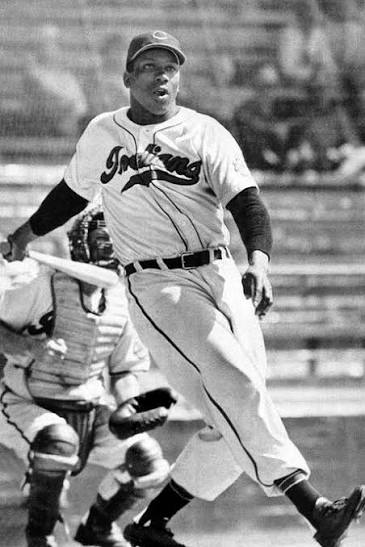

One former Negro League star who got a relatively large amount of ink in Jet was big Luke Easter, a giant slugger who crushed towering home runs for the Homestead Grays before hopping to the Cleveland Indians in 1949.

The magazine chronicled Easter’s career with the Indians in the early- to mid-1950s, and then into the later 1950s and beyond in the minor leagues, where he became something of a folk hero. Jet began publishing after Easter’s tenure with the Grays, so the publication never really covered his time with them.

While Easter was with the Indians (now renamed the Guardians), Jet reported on the injuries that limited his playing time and production, and the magazine made note of his tape-measure circuit clouts, as well as his contract news.

But it was Easter’s lengthy career in the minors and his post-playing retirement that the magazine really followed. In addition to noting how Easter frequently led various leagues in homers and RBIs, the post-MLB coverage of Easter included the indefinite suspension he drew in August 1955 for tossing balls to kids in the stands; his setting of the International League’s season home run mark in 1956 with 35 for the Buffalo Bisons; a $100 fine for his role in instigating an in-game brawl in June 1958; and being named the Indians’ first black coach in 1969.

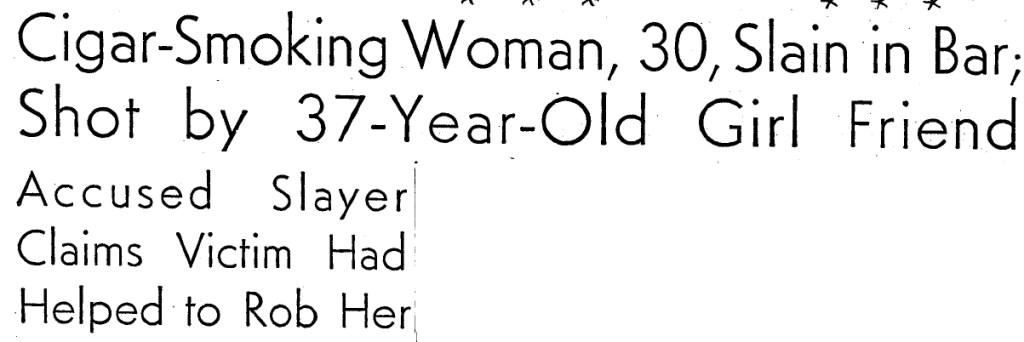

Sadly, Easter was murdered by robbers in Euclid, Ohio, at the age 63, and Jet dedicated an entire page to remembering the legendary slugger. The piece ended with a quote from Bill Veeck, the eccentric baseball owner/executive who signed Easter to the latter’s first big-league contract with Cleveland in 1949.

“It’s really sad,” Jet quoted Veeck as saying. “He was a heck of a guy. I remember him hitting 25 homers in one month in the minors. If he could have come into the majors sooner, there’s no telling how great he might have been.” (Veeck was noted for embellishment and hyperbole.)

In addition to the activities of individual former Negro League players, Jet also periodically tracked the status of the fading Negro American League, which, by the time Jet came started publishing, had already been decimated by the exodus of its players into Organized Baseball post-integration.

In May 1954, the magazine announced the opening of that year’s NAL season, noting that only four teams were now in it. Five years later, Jet reported that the NAL was willing to take offers from the American and National Leagues to become an official minor league under a financial partnership. However, the NAL, the publication noted, would not take organizational tie-up offers from individual AL and NL teams. (The NAL would further fade into obscurity and fold within a few years.)

(In that same April 23, 1959, issue of the weekly, it’s worth noting, Jet reported that Pumpsie Green had been sent back to the Boston Red Sox’s top farm club, the Minneapolis Millers of the American Association following spring training. Three months later, Green made his BoSox debut to integrate the Boston club, the very last Major League team to do so.)

As a side note, in March 1954 Jet noted the formation of the Eastern Negro League, a group of clubs from the East and the South that planned a two-division circuit with eight teams in each division, for 16 total. (The ENL didn’t last very long, for a couple seasons at most.)

(Coincidentally, and in news that became, in hindsight, much more significant that the ENL, in that same March 25, 1954, issue of Jet, the weekly noted the signing by the NAL’s Indianapolis Clowns of two women players, Connie Morgan and Mamie “Peanuts” Johnson, as well as a new field manager – none other than the great Oscar Charleston.)

Jet also kept tabs on the once-great teams of the Negro Leagues as they struggled to survive as integration continued to sweep across Organized Baseball. In February 1956, for example, the publication reported that according to Kansas City Monarchs owner Tom Baird, the Monarchs were faced with the prospect of either leaving Kansas City or disbanding. Baird cited two causes for the dilemma – skyrocketing costs, and the entry of the Major Leagues into the local market, with the arrival of the Athletics.

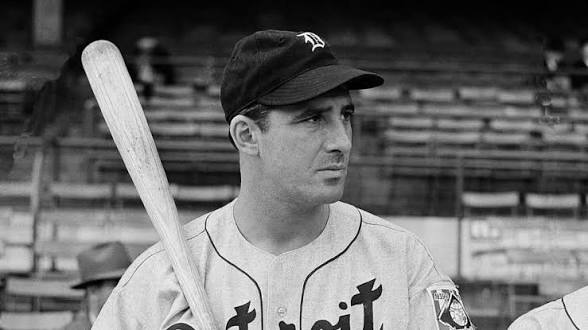

As time went on, into the 1970s and ’80s, Jet reported on the induction of pre-integration African-American players into the Hall of Fame in Cooperstown. In March 1967, the magazine made note of the death of pitcher Wilber “Bullet” Rogan, and more than 30 years later, Jet reported on Rogan’s election to the Hall in 1998.

“Known for a quick, no-windup delivery, a blazing fastball was Rogan’s primary pitch,” the publication stated before adding that Rogan was also adept in other positions (particulary outfield) and at the bat.

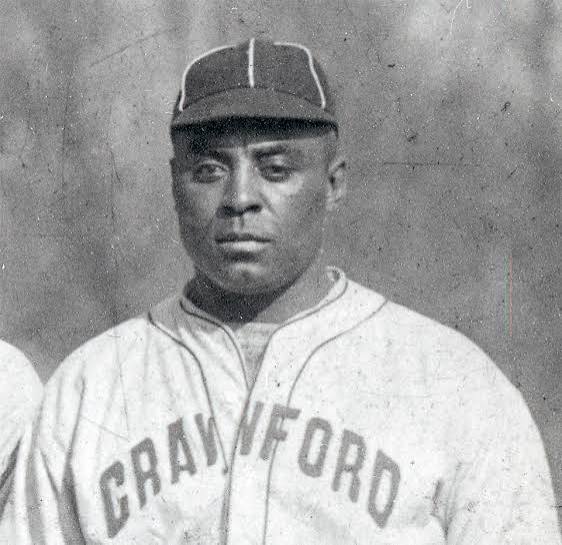

Likewise, in October 1954 – roughly three years after its launching – Jet gave a handful of lines to the great Oscar Charleston, who was and is considered by some (including this humble writer) as the greatest player of all time, regardless of color, league or era. Then, in 1976, as Charleston was being ushered into the HOF, the publication dedicated a full page to his memory and, by extension, the memories of many Negro League legends.

“He was a compactly muscled 190-pound athlete who stood 5 feet, 11 inches and who, like to many of his fellow Negro League players, was forced to wallow in baseball obscurity,” the magazine stated.

“But that didn’t stop the late Oscar Charleston from playing with a passionate fury, relentlessly attacking any pitcher’s best stuff,” it added.

The article concluded with nods to other Black baseball greats and added that many Negro Leagues legends deserved their own calls from the Hall.

“There is still a rich quantity of Negro League stars awaiting a Hall of Fame nod,” it stated. “Last year the [Hall of Fame’s] special committee [on the Negro Leagues] talked of dissolving. Fortunately for those Black players whose only blockade into the Major Leagues was white racism, the committee continues to breathe.”

Other legends whose HOF inductions were reported by Jet included pitcher/manager/team owner/executive Rube Foster, third baseman Judy Johnson (March 1975) and pitcher Leon Day (March 1995), who, the magazine noted, received the Hall’s call while he was in his bed at St. Agnes Hospital in Baltimore.

“I thought this day would never come,” Day said, a comment to the New York Times that Jet included in its own article. “I’m feeling pretty good. I’m not as sick as they think.”

Day died six days later.

Jet also noted the passings of shortstop Willie Wells (April 1989), third sacker Ray Dandridge, (March 1994) and Effa Manley (May 1981), co-owner of the Newark Eagles.

On the subject of Effa Manley, four years before her death Jet published an article about her then-new autobiography, co-authored with sports reporter and publicist Leon H. Hardwick, entitled “Negro Baseball … Before Integration.”

In the Jet’s article on Effa and the book, the magazine asserted that while Effa’s husband, Abe Manley, using profits from his numbers racket to fund the Eagles, recruited the club’s players and “mapp[ed] the team’s field strategies. …it was Mrs. Manley who took care of the books and saw to it that on every first and 15th day of each playing month the Eagles’ paychecks would fly to the players’ pockets.”

The magazine added that “[h]er personal story is as colorful as the brand of ‘devil-may-care” of baseball played in the Negro Leagues. …

“An admitted Babe Ruth fan years before she moved up to management, Mrs. Manley recalls with fondness the days that her Eagles stocked such playing gems” as Monte Irvin, Larry Doby, Biz Mackey, Wells, Mule Suttles, Dick Lundy and Day.

In being interviewed for the Jet story, Effa expressed sadness that integration killed the Negro Leagues – she said the Black circuits “could have been a magnificent farm system for the major league teams” – and sharply criticized Branch Rickey for starting the trend of major league team owners poaching talent from the Negro Leagues.

“Branch Rickey was terrible for what he did,” she told the magazine. He got some of our best players for nothing even though we had a vested right to our players.”

Manley also said the Negro Leaguers who were starting to trickle into the Hall of Fame in the 1970s should have been placed in a separate wing in the Hall, because such a section would allow for more segregation-era Black figures to be inducted overall.

“I’d settle for seeing 25 or 30 of those Negro League players in the Hall of Fame at once,” she told the magazine, “but in my book there’d be even more. Negroes should know how great they are. It’s ridiculous for Negroes to think they’re inferior.”

(There are currently 37 Negro League figures in Cooperstown, including Effa Manley, who was inducted in 2006, along with 16 other segregation-era Black baseball representatives, the last Negro Leaguers to date to go in.)

In ensuing years, Jet also highlighted other ways Negro League greats have been recognized and honored over the decades. Primary among that are periodic articles about the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City – in December 1990, the publication reported on the founding of the museum; in 2008, Jet revealed how rappers Kanye West, T-Pain and Big Boi were part of a special CD aimed at benefiting the NLBM; and in February 2010, the magazine discussed how the museum was experience devastating financial difficulties. (The NLBM is now gladly on solid fiscal ground and doing phenomenally.)

A few other recognition events for Negro Leaguers covered by Jet:

- The Chicago White Sox in 2008 hosting a tribute to the 75th anniversary of the first edition of the famed annual East-West All-Star Game. The salute included the Double Duty Classic game, featuring 30 inner-city high school players and the attendance of several legendary MLB and Negro Leagues greats.

- The 1990 edition on the Baseball Encyclopedia including the names and statistics of Negro Leaguers for the first time. That year the compendium listed about 130 segregation-era Black players. Jet quoted encyclopedia editorial director Rich Wolff: “When I realized that some of today’s big-leaguers do not even know who Jackie Robinson was, I realized it was time we did something about it.”

- The erection of a monument honoring Josh Gibson and Rube Foster in a park in Marietta, Ga., the site of the Twelfth Annual Georgia Negro Baseball Tournament in 1960.

- The National Baseball Hall of Fame in June 1991 hosting more than 60 former Negro Leaguers during a special reunion in Cooperstown, with Henry Aaron and then-NL President Bill White scheduled to attend. Stated then-Hall President Ed Stack in Jet’s article: “The Hall of Fame is delighted to pay tribute to these pioneers of the game.”

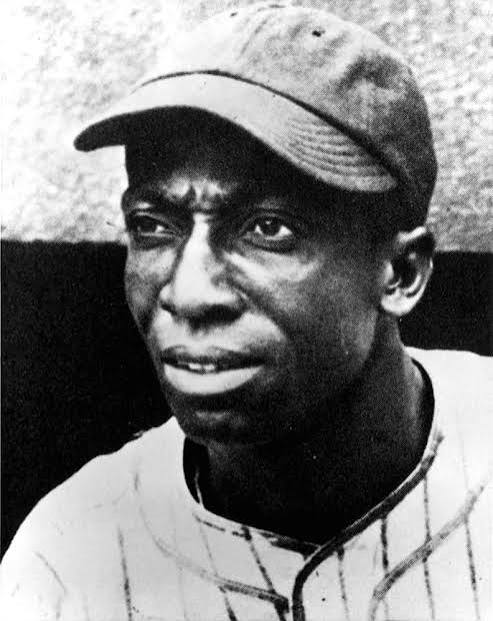

I want to conclude with how Jet chronicled the later life of the one and only James “Cool Papa” Bell, because the publication devoted a good deal of page space to the legendary Black baseball speedster and outfielder.

In October 1954, the magazine reported the 51-year-old’s formation of an all-Black barnstorming team to travel with an all-white club; in summer 1986, Jet included a picture of Bell, then 83, tossing out the first pitch at a Boys Club stadium in his adopted hometown of St. Louis being renamed after him.

That was followed in March 1990 by a brief feature article updating readers on Bell’s memories and current life; the story was accompanied by a photo of the baseball great holding a framed image of his Hall of Fame plaque. On a more dour note, later in 1990 Jet reported on the theft of $300,000 in memorabilia owned by Bell and the legal case against the alleged pilferers.

Then, in March 1991, the magazine ran a long article about Cool Papa’s death at the age of 87 (the article erroneously said 88) after a long illness. Stated the story: “Bell was thought to be the fastest man ever to play baseball and was a terror on the basepaths.” The piece also noted, however, that Bell was also an excellent hitter, something in which the late outfielder prided himself.

Fortunately, though, the baseball legend was posthumously honored about three years later, as Jet reported, with the renaming of a street in Jackson, Miss. (he was born in Mississippi), as Cool Papa Bell Drive; the effort to rename the roadway had been headed up by Bell’s daughter, Connie Brooks.

While Home Plate Don’t Move will never be put behind a paywall, donations of any size are welcome. To donate to the blogging effort, click here.