Former Vice President Charles Curtis

It’s been way too long since I’ve gotten off my big duff and back on the blogging trail, for which I apologize tremendously. I’ve had trips to visit family and a week of dogsitting a surprisingly spry 10-year-old golden retriever named Van Gogh.

I’ve also been kind of bogged down by the sheer mass of stuff about which I’ve wanted to write lately – it’s been so hard to pick out which juicy topic to attack first and bring to y’all.

As a result, which this post on the Fourth of July, I’ve tried to tie in as many of these scattershot subjects into one post. I’ve also hopefully come up with something quite appropriate for the 240th celebration of our country’s independence from those dopes who just voted to tank the global economy. (I want to note, though, that both Northern Ireland and my distant relatives in Scotland voted for sanity and to stay put, but their level-headedness was overwhelmed by a slew of jingoistic knuckleheads. Alas.)

Anyway, this post is about that most American of cities, Washington, D.C., and it also brings a whole bunch of stuff together.

But fair warning – this is the longest blog post I’ve ever written. It’s several thousand words long, so be prepared. Hopefully I’ve put it together well enough that it flows in some coherent manner, but I’m sure at spots it rambles a little too much and skips off into the meadows every once in a while.

So here we go …

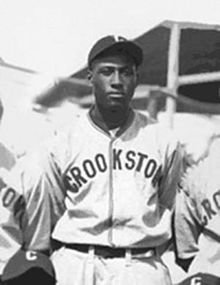

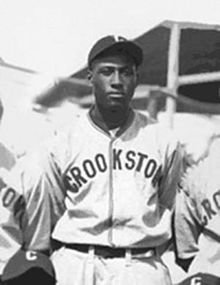

One subject that I’ve unfortunately let wither over the last month of inertia is legendary catcher Bruce Petway, one of the best African-American backstops of the 1910s and ’20s and arguably one of greatest defensive catchers in baseball history, black or white.

Bruce Petway

I wrote a post about him here, but that was a while ago, and, with his 100th birthday being marked today, Independence Day, I figured it might be a good time to revisit his story. In

addition, this month I have an article out in Nashville Lifestyles about Petway – a native of the Music City – and the Negro Leagues scene in that Tennessee metropolis.

As my work on Petway progressed, I strove to pitch a story or two to publications in Detroit, where Petway had suited up most famously for the Detroit Stars from 1919 to 1925.

But here’s a twist – over the last year of researching Petway’s life and career, at the same time I’ve been poking around some other quirky topics embedded in blackball history. One strand of inquiry stemmed this year’s already volatile presidential campaign and upcoming election in November. I was curious about whether any politicians – especially presidential candidates – from the past, in an effort to court the African-American vote, ever appeared at Negro Leagues games or events in any official capacity.

Another low hanging piece of historical fruit in which I’ve always been interested is the 1932 East-West League, an effort by Cum Posey, the Hall of Fame owner of the Homestead Grays, to pull together a formal Negro League after the demise of the first Negro National League the previous year. The NNL’s disintegration meant led to the prospect that the 1932 baseball season would pass without a top-level, or “major,” Negro League in existence, and Posey attempted to fill that void.

Theeeeeeen, while all that was going on … I’ve been working steadily (although, unfortunately, I admit, not as diligently as I should) on an article for a publication in Charleston, S.C., about that city’s involvement in the landmark 1886 Southern League of Colored Base Ballists, the first known attempt at a regional professional “colored” base ball (two words back then) circuit. Springing from my work in that area was a curiosity about any other important Palmetto State connections to African-American hardball.

Aaaaaaaaaand, while all of that stuff was percolating, I had in the back of my mind that 2016 – July 9, to be precise – marks the 50th anniversary of the death of Hall of Fame first baseman and legendary blackball slugger Mule Suttles, which prompted me to investigate any ways I could write about that milestone for various publications.

Mule Suttles

With all of these lines of inquiry floating around in my noggin, I eventually – and, perhaps, unlikely – tripped over a topic that amazingly brought all of those strands together – the Washington Pilots.

While much of this thought process tumbled along months ago – therefore, admittedly, rendering my memory of the whole thing a little fuzzy – I think my first inkling about the Pilots was stirred by my poking around the whole politics angle.

As I was searching various databases for info about politicians visiting Negro League games, I came across this post by Gary Ashwill on his outstanding blog, Agate Type. In the piece, Gary discusses how, in May 1932, then-Vice President Charles Curtis appeared at Griffith Stadium to throw out the first ball at the opening game of the … 1932 East-West League! The teams taking the field that day? The storied Hilldale Club of Philadelphia and … the Washington Pilots!

Setting aside the baseball angle for a moment, Charles Curtis, despite an intriguing personal story, seems to be relegated to the dustbin of American political history. Curtis, who interestingly possessed a strand of Native-American lineage, was a native of Topeka, Kan. Born in 1860, about a year and a half before the start of the Civil War, became a lawyer in young adulthood before scaling the political heights – first as an eight-term Congressman, then as a U.S. senator from Kansas from 1907-1913, then again from 1915 through 1928.

That experience turned Curtis into a major power player in D.C., where he served first as the Republican whip in the Senate, then as party majority leader. He specialized in Indian relations, national defense, natural resources and, most crucially, agriculture. He also solidified his reputation as a strict, dedicated adherent to the rule and letter of the law.

That tenure, especially his advocacy of farm relief, prompted GOP presidential candidate Herbert Hoover to select Curtis as his running mate. The pair triumphed in November 1928, with Hoover succeeding fellow GOP president Calvin Coolidge, who had retired.

But then disaster happened – the stock market crash of October 1929, which plummeted the national economy into the Great Depression, a situation that immediately and starkly soured the American populace on the Hoover administration.

A panicked crowd mobs a New York bank after the crash

The administration’s feeble attempts to pull the country out of the Depression were utterly dismal, and the economic morass dragged on and on. At the same time, the Democrats nominated the charismatic, ambitious – and, some say, visionary – Franklin D. Roosevelt as their candidate, making the 1932 presidential election essentially a referendum on the future of the national economy and the role government should play in it.

Needless to say, Hoover and Curtis had a massive uphill battle facing them, which doubtlessly prompted Curtis to campaign tirelessly in an effort to boost the Administration’s abysmal public approval rate.

At that time, the Republican Party was still the go-to organization for most of the country’s African-American voters, or at least the ones outside of the South, where Jim Crow had for decades shut blacks out of the political process. The GOP remained “the party of Lincoln,” the Great Emancipator.

Meanwhile, the Depression had hit the country’s African-American population especially hard; by 1932, black unemployment hovered around a staggering 50 percent, significantly more than the population as a whole, and white animosity toward black workers constantly simmered just below the social surface. In addition, the U.S. military remained segregated, and lynchings continued to be a rising scourge on black life, especially in the South.

As a result, it could be argued that Hoover/Curtis, as the standard-bearers of the supposed “party of Lincoln,” knew they needed to court the African-American vote. One way to do that? Show up at a Negro Leagues game and mug for the cameras.

Chet Brewer

Thus, perhaps, Curtis’ involvement in the Washington Pilots-Hilldale Club game in late May 1932. The VP’s presence did indeed make a splash in the media, especially the African-American press, which ran huge photos of Curtis winding up to throw out the first pitch from the stands. The Pilots’ Chet Brewer received the toss while other national officials – such as Assistant Attorney General C.B. Sisson and Republican National Committee director A.H. Lucas – looked on. Also in the VP’s box in the stands were Pilots officials H.E. Jones, R.B. McCoy and John Lucas (apparently no relation to A.H. Lucas), and more on that trio later …

Alas, all such PR efforts failed for Hoover and Curtis, who were crushed by FDR in the general election, triggering a massive political realignment in the country. Roosevelt famously launched the New Deal, which greatly enlarged the size of government by creating several social welfare programs that still exist today, as well as intensive job-building efforts such as the Works Progress Administration.

Coupled with the GOP’s distinct hesitation – as embodied by Hoover’s previous policies – to involve the government in addressing the Depression – FDR’s policies turned the Democrats into the country’s supposed “progressive” party and the GOP into the “conservatives.”

With that, the country’s black population gradually shifted its allegiance to the Democrats, a trend strengthened a couple decades later, when the GOP’s Richard Nixon launched a concerted effort to turn the conservative white South into a Republican-dominated voting bloc — the infamous “Southern Strategy.”

To wit, here’s an excerpt from an article on the Library of Congress Web site:

“Although most African Americans traditionally voted Republican, the election of President Franklin Roosevelt began to change voting patterns. Roosevelt entertained African-American visitors at the White House and was known to have a number of black advisors. According to historian John Hope Franklin, many African Americans were excited by the energy with which Roosevelt began tackling the problems of the Depression and gained ‘a sense of belonging they had never experienced before’ from his fireside chats.”

Curtis, meanwhile, retired from public office after leaving the vice presidency but did maintain an interest in public affairs before passing away in February 1936 and being buried in his native Topeka.

Although Curtis has become little more than an historical footnote – the unfortunate fate of many a vice president, but especially for a one-termer who served in one of the most unpopular administrations of the last 100 years – he remains respected by historians for his character and dedication to serving the people. He received similar plaudits from the contemporary press at the time of his death. Stated the Feb. 9, 1936, New York Times:

“He was one of the few Vice Presidents positively to enjoy the office. He relished those social obligations even a partial census of which makes you think of the interminable drudgery of a Prince of Wales or a Royal Duke. He worked hard. It was a pleasure for him to play hard. …

“He was’ a character.’ His shirt was unstuffed. Within the circle of his doctrines, he served his country well. But it is the man with good Tawny blood in him and some tang of the frontier, his friendly qualities, his veracity, his little harmless vanities, that gained the good-will of persons who hated his politics.”

(Question: Does anyone know what Tawny blood means?)

But enough of my babbling about politics – I did, after all, double-major in political science as a undergrad, a decision that has often remained useless throughout my journalistic career.

Back to baseball! …

Thus, thanks to Gary Ashwill’s post, I was tuned into the Washington Pilots. And, because the Pilots were members of the 1932 East-West League, this newfound knowledge intersected with my ongoing interest in that Cum Posey-led circuit.

Then I checked out some of the players on the Pilots’ 1932 roster, a list that included … Mule Suttles, who died exactly a half-century ago this week! Bingo! Another strand of research leads to a central vortex of history.

In addition, one figure who was heavily involved in the creation of the East-West League was Hall of Famer Ben Taylor, a first sacker and one of the famous Taylor brothers quartet who collectively played an intricate roll in the development of Negro baseball for three decades in the first half of the 20th century. The Taylor brood also included famous siblings C.I., Candy Jim and “Steel Arm” Johnny.

Ben Taylor

Taylor did indeed get in on the ground floor with the new league, even playing a crucial role in the discussions that coalesced between various owners and execs in late 1931, after it became clear that the (first) NNL was kaput.

As it turned out, one of the final and most conclusive meetings occurred in Washington, D.C., in mid-October. In an article in the Oct. 24, 1934, issue of the Baltimore Afro-American, special correspondent S.B. Wilkins reported that a group of mostly Eastern baseball moguls had agreed to pull together a new, eight-team league.

However, what were termed “Western observers” also showed up, including Ben Taylor, who was ostensibly representing the Indianapolis ABCs. On top of that, the article asserted that Taylor was one of several managers at the meeting who were seeking gigs with one of the new eight franchises.

Also, most interestingly, Wilkins reported that Taylor had previously proposed an East-West league that encompassed aggregations from both the East Coast and the Midwest, but Wilkins wrote that the proposal “was deemed inexpedient at this time.”

However, at some point the nascent loop’s execs did, in fact, decide on an East-West League, apparently picking up on Taylor’s previously rejected idea. And while Taylor didn’t land a managerial job in the circuit, league execs tapped the venerable member of Negro baseball’s first family an umpire for the upcoming season. In fact, the Afro-American’s Bill Gibson reported, in cryptic-yet-common-for-the-day language, in April 1932 on the league’s targeting of Taylor for the blue crew:

“And before I leave the local baseball situation, I understand that ‘Uncle’ Ben Taylor, who piloted the Sox through many successful seasons, is being sought by the East-West League as an umpire. The pillar is for Ben. He fits into the picture nicely, eh, wot?”

Wot?

Added Pittsburgh Courier columnist Rollo Wilson a few weeks later:

“While Ben Taylor has not been conspicuous as an umpire, his background is such that he should be a success. Serving as a player, manager and owner, he is familiar with every angle of the game.”

Added an un-bylined article in the same issue of the Courier a few weeks earlier:

“Benjamin H. ‘Brother Ben’ Taylor, famous scion of that of that illustrious Indianapolis baseball family, has been appointed as one of the umpires in the East-West League. Ben handed in his application when the league moguls met in Washington after failing to land a berth as manager of one of the clubs in the loop. Taylor’s decision to take umpiring is commendable due to the fact that Ben, for many years star first baseman of his immortal brother C.I.’s Indianapolis ABCs, is the first one of the major stars to give consideration to turning to another part of the game that they know so well.”

So, hmm, though, where else did I know Ben Taylor’s name from … Oh right, from my digging around South Carolina Negro League history – Ben was from Anderson, S.C.! He was born in that burg on July 1, 1888, and went on to enjoy a lengthy, diverse, well traveled Negro Leagues career that led to posthumous induction into Cooperstown in 2006.

Enhancing this wild and wooly tale is the fact that the 1932 league wasn’t Ben Taylor’s only link to the nation’s capitol – in 1923, he helped conglomerate the Washington Potomacs, who a year joined Philadelphia’s Ed Bolden’s Eastern Colored League, which served as a second “major” Negro League to rival Rube Foster’s NNL from 1923-28 before its own demise. The ECL became notorious for its renegade ways, which included raiding NNL teams for talent and brashly challenging the NNL to the nation’s first editions of a “Colored World Series.”

Ben Taylor recruited his brother, Steel Arm Johnny, to anchor the Potomacs’ pitching staff. However, the Potomacs – and therefore the Taylors’ tenure in D.C. – didn’t last very long. Ben Taylor bailed after the ’24 season, and in 1925 the franchise shifted to Wilmington, Del., where it quickly collapsed altogether. (Want more on Delaware, btw? Check out this, this and this. The history of blackball continues to be complex but always interconnected.)

(Also, it should be noted that at least one online biography and directly links Taylor of the Washington Pilots themselves, but I’ve found no real proof of that.)

Steel Arm Johnny Taylor

Sooooo … so far in this winding narrative the Washington Pilots have brought together presidential politics (via VP Curtis), Mule Suttles (the Pilots’ Hall of Fame first baseman), South Carolina (via umpire Ben Taylor) and the 1932 East-West League (in which D.C. was a charter franchise).

Now, what about some of the other topics that’ve been careening around my brain – namely, Bruce Petway and the Detroit Negro Leagues?

That’s where the story of the Washington Pilots themselves comes into play. It’s also where I must apologize for now engaging in a moderately embarrassing bait-and-switch. …

Petway didn’t play for the Pilots, and I couldn’t find any meaningful connection between him and the franchise. I know I roped you in partially by hinting at more Bruce Petway with this, but alas, there really isn’t.

But there is, via him, a connection between the Pilots and the city of Detroit … Petway spent the latter half-dozen years of his career with the Detroit Stars, one of the top teams in the later days of the first Negro National League.

And Detroit ended up playing a crucial part in the Pilots’ story, as we shall see …

The nation’s capitol played a key role in the plans of the East-West League from the very beginning – in February 1932, the press trumpeted the creation of the Pilots, whose ownership, including John Dykes and Bennie Caldwell, were immersed in the D.C.’s vibrant club, social and cultural scene, a fact that made them, seemingly, a strong asset to Posey’s nascent circuit.

For example, in January 1932, the Baltimore Afro-American’s Trezzvant W. Anderson penned a gushing piece about how teenaged Elmer Calloway, kid brother of famous swing band leader Cab Calloway, had secured the gig as house band leader at the businessmen’s Club Prudhom. The joint’s owners, in turn, displayed their penchant for success and all things outsized and glamorous. Wrote Anderson:

“Entering the Club Prudhom was the first ‘big’ assignment of young Calloway, and whether he relished any misgivings about the chances of success or not, I could tell you, but won’t. But he took his band in there and, supported by the already famous name of the Calloway clan, the slender lad began his work under the able ministrations of Bill Prather, Rhody McCoy, John Dykes, and Lonnie Collins, all makers of celebrities.

“Broadcasting was a much considered idea in the heads of the operators of the growing little club, which was regarded curiously at first as an experiment, until the owners began to show the Capital that they meant business. …

“Facing this psychological atmosphere, Elmer swung into his work with all the enthusiasm of youth … and results began to come.

“Patronage at the Prudhom began to pick up; crowds grew each night, the popularity of the hot spot of Washington’s Harlem became a certainty; and before long Prather and his associates knew that broadcasting and further expansions would be worthwhile, and so they inaugurated that program. …”

Why, with such a record of success backing it up, how to Negro baseball fail in D.C.? In the Pittsburgh Courier’s Feb. 13, 1932, reporter Lloyd P. Thompson asserted that, after Caldwell, Dykes and promoter “High Powered” Doug Smith put on a handful of allegedly well attended and successful baseball promotions in 1931 after a good deal of hustling and personal investment, Washington’s movers and shakers sensed the potential for something grand, and when Posey created the East-West, they knew their opportunity had arrived. Wrote Thompson:

“This and a couple succeeding promotions by Smith set some of the Washington boys who were in the know class thinking there was gold in them that concrete enclosure [the Senators’ Griffith Stadium] and to have a couple of ringer clubs from the outside toting it off was all wrong, and subsequently a home ball club, the Washington Pilots, was launched on paper. The delegation waited on Smith with the ink still wet on their letter heads informing Doug that he was major-domo of all that he surveyed, but when the delegation was informed that they only needed about ten grand to go with the stationary, the good ship Pilots cracked up before it left the ways. However John Dykes who specializes in finance and floor revues has stepped into the breach and with Doug Smith and Bennie Caldwell the Washington entry is in. Oh! And about the ball club – well, that’s another story.”

As we’ll see a bit later on, the D.C. power quartet – Caldwell, Dykes, Smith and Roy McCoy – weren’t all they seemed to be. But for now, the news of the Pilots’ birth supposedly created jubilation both in the nation’s capitol and within the head offices of the East-West League. Stated the March 31, 1932, Philadelphia Tribune:

“Nowhere around the circuit of the East-West League is there more pep and enthusiasm about the fast approaching season than at Washington, D.C. Manned by the combination of John Dykes and Roy McCoy in the heavy roles, the Washington Pilots … with [their] complete personnel aside from players [are] humming with activity to give the Capital [sic] City fans something to talk about when the corners around Ninth and You [sic] streets get cluttered up during the coming baseball season. …”

The team’s owners finagled the securing of the wily, wise and wicked Frank Warfield as the club’s first manager by snapping him up from the Baltimore Black Sox, thereby also securing a built-in Beltway rivalry between the two squads – one that was slated to be consummated when the two franchises faced off in the season opener.

Frank Warfield! Remember him? Earlier this year I argued his case for induction into the Baseball Hall of Fame, a belief I stick to now. If the Hall does end its current, shameful exclusionary policy and justly reopen its doors to blackball figures, the Weasel more than deserves heavy consideration.

And there’s more along those HOF lines! The Pilots also secured the services of another wizened blackball veteran – none other than Harrisburg’s Rap Dixon! As I’ve chronicled several times in the past (including here), my SABR buddy and Malloy roomie Ted Knorr has been lobbying Rap’s case for Cooperstown, and I certainly agree!

Also on the Pilots’ early roster was Chet Brewer (who would later catch an opening pitch from U.S. VP Charles Curtis, if you recall), Nip Winters and submarine pitcher Webster McDonald. After a harried few days of training camp, the D.C. pro team worked its way through a quick exhibition slate – including an embarrassing, season-opening loss in Wilmington to the semi-pro white Camden squad of Lou Schaub before opening E-W League play in mid-May.

Nip Winters

The Pilots squared off against league foes like the Baltimore Black Sox, from whom the D.C. crew took two of three games to pry open in lid on the league slate; the Hilldale Club, who clobbered the Washington squad at the latter’s home debut at Griffith; Syd Pollock’s Cuban House of David (whom, Gary Ashwill notes, were not that serious of a team, at least at the time), who took the measure of the D.C. team, 10-3, in an early June match; and the Black Sox again, who turned the tables on their rivals by beating the Pilots twice under the lights in night games and in a 13-inning thriller.

Unfortunately, as was the case with the first NNL, the ECL, the different incarnations of the Negro Southern League and other pro blackball circuits, the East-West suffered from shoddy record-keeping and lackluster, often biased reporting of game results by its member teams.

That led to different newspapers publishing vastly different league standings on the same day; in its May 21 edition, for example, the Baltimore Afro-American published standings that had (perhaps predictably) the hometown Black Sox in first, followed by the Detroit Wolves (remember them for a bit later), the Pilots and the Cubans, while the Pittsburgh Courier from the same day posted a bracket that had the Pilots, Wolves, Grays and the Cubans at 1-2-3-4.

Such chaos contributed to a major league shake-up in early June, an earthquake also spurred by horrendous gate receipts, outsized operating costs and general public and institutional apathy. Under the blaring headline, “East-West League Introduces Drastic Changes,” the June 11, 1932, Afro-American laid it all out after a league tete-a-tete in Philly:

“Club owners of the East-West Baseball League met … here this week and after wrestling with their problems in a session that lasted all night, decided that only radical changes would permit any of the clubs to continue because of adverse business conditions and financial reverses up to the present time.

“The policies debated and adopted for the continuation of the league and some of the individual clubs were boiled down to three major issues: drastic cuts in salaries and overhead operating expenses, revision of league schedule and discontinuance of the plan of everyday baseball, and discontinuance of employing monthly salaried umpires. These changes went into effect after June 5.”

But there were other disheartening moves as well. Syd Pollock and his Cubans were reported to have bailed entirely, and Posey was begrudgingly forced to admit his personal Steel City rival Gus Greenlee, owner of the Pittsburgh Crawfords, into the loop. In addition, the Cleveland club was nudged into a so-called co-plan – its players wouldn’t receive set salaries, but a portion of the already meager gate take instead.

(It’s semi-important to note that Posey’s invitation to Greenlee in all likelihood was made with extreme bitterness – in the off-season, Greenlee had unashamedly poached the Grays’ brightest lights, including Josh Gibson, Cool Papa Bell and Oscar Charleston, a move that absolutely crippled the Homesteaders on the field and at the gate.)

There was also one more alteration, one that finally connects (albeit, admittedly, tenuously) the city of Detroit with the Washington Pilots – the collapse of the Detroit Wolves. Some of the Detroit roster was absorbed by the Grays – a natural occurrence, since Cum Posey conveniently owned both franchises – but the rest was put up for sale and/or draft to the league’s other teams.

That roster-juggling proved to be a boon for the Pilots, as they inherited none other than Mule Suttles from the Detroit Wolves! The E-W shakeup brought the D.C. club a slew of other stalwarts , including hurlers Leroy Matlock and Ted Trent, third sacker Dewey Creacy, outfielder Bill Evans, and catcher Mack Eggleston. Finally, Washington lured sparkplug shortstop Jake Dunn from the Los Angeles Royal Giants, giving the Pilots what appeared to be one of the East-West’s strongest lineups.

Quirkily, though, is the fact that for much of the East-West’s 1932 campaign — or at least the portion when the Wolves actually existed — the Detroit club completely owned the Pilots on the field. In late May, for example, the Wolves busted out their brooms to talk all four games of a series against D.C. in Detroit, including taking both games of a series-ending twin bill.

That sweep and a bunch of other W’s — a record triggered by an airtight defense that led the league in fielding percentage — propelled the Wolves into first. It didn’t get much better for the Pilots, either — when the Washington squad came to Detroit, the Wolves absolutely plastered the Pilots, 16-1, in the first end of a doubleheader at Hamtramck Stadium. (The second contest was stopped by Jupe Pluvius.)

The May 29, 1932, Detroit Free Press

And it’s doubly interesting, perhaps, that the Wolves themselves were created by benefiting from another team’s misfortune. When the first NNL tanked at the end of 1931, its last champions, the St. Louis Stars, also collapsed, triggering a free-for-all for its players. According to spring 1932 media reports, the Wolves landed seven members of the previous year’s St. Louis team, including Cool Papa Bell, Suttles, fellow Hall of Famer Willie Wells, Creacy, Trent and Quincy Trouppe. In fact, the Wolves aggregation that emerged in early ’32 was virtually a brand-new one from an iteration from 1931. Stated the May 5, 1932, Detroit Free Press:

“Not a member of last year’s club has been retained. with the reorganization of the old Negro National League came a higher class of ball.”

Anyway, the re-jiggering of the league structure doesn’t seem to have mattered, though – the circuit stumbled and tripped and collapsed by the end of the season, leaving the unlikely Negro Southern League as 1932’s only sustained, “major level” blackball circuit. (Greenlee would launch the second NNL in ’33, quite successfully.)

The D.C. aggregation managed to sputter toward the fall and assemble something resembling a second half of a baseball season, including a road trip filled with scheduled visits to Philadelphia and Pittsburgh, as well as, in late July, playing in the first-ever night game in Washington, a 5-1 loss to the Crawfords under the lights at Griffith Stadium.

Frank Warfield

Unfortunately, however, Frank Warfield died suddenly just a few weeks later, leaving Webster McDonald in possession of the managerial reins.

Still, according to the Sept. 5, 1932, Washington Post – the city’s major daily actually provided the Negro club with pretty decent coverage – the Pilots returned to D.C. sporting a sterling 14-5 mark during a recent, lengthy road jaunt, and by the end of the summer the D.C. bats – especially those of Suttles and catcher George “Pep” Hampton – had come alive. Both trends reflected of what the Pilots might have been capable if they’d been birthed into a league with more sturdiness and accountability than the East-West.

Clark W. Griffith

And, most importantly, the positive aspects of the Pilots’ stay in Washington didn’t go unheeded, because at least one of Organized Baseball’s kingpins was paying attention. In early August, reporter Trezzvant Anderson, now with the Associated Negro Press, scored an interview with powerful Washington Senators mogul Clark W. Griffith himself, and the American League club’s owner apparently had very good things to say.

Anderson, who caught Griffith as they attended a night game in D.C. between the Pilots and the Crawfords, wrote that the white owner:

“… declared that he believed that high class baseball for Negroes would pay, and that it should flourish, if properly organized and supported by hometown fans where the teams were located. …

“He asserted that Negroes deserved high class baseball, for he has recognized the fact that Negroes are just as discriminating as whites in their desire for the best, and he said that he was sure that they could get the best, for just then he was watching two of the best teams in colored big league baseball play …

“It is his belief that those behind Negro big league baseball should do everything possible to give their fans the very best they can get …

“But, said Mr. Griffith, it is almost impossible to have success with big league baseball unless the fans in the team’s hometown take an interest in their team and consider it as their own, a proprietory [sic] interest, which would be reflected in the efforts of the players to justify the feeling.

“The playing of these big league Negro teams as duly impressed Mr. Griffith, and his interest was clearly shown as he sat and watched each play like the baseball hawk that he is and has been for thirty-six years, during which he has had every experience baseball has to offer …”

Anderson reported that Griffith worked with a local firm to bring extra lighting to the Pilots’ night games that season, in addition to use of Griffith Stadium’s own illumination sets, apparently out of the goodness of his benevolent heart.

He also made a point in lauding the Negro talent he was seeing at his stadium that year, especially with Dixon and Suttles. In addition, Griffith lavished praise on Pilots owner Dykes, calling him a “clean-cut fellow” who would undoubtedly [with Anderson paraphrasing] “bring colored baseball to a high plane in Washington.”

Concluded the reporter:

“Commenting on the failure of the Negro National Baseball League a year ago, Mr. Griffith said that it was necessary that the race have leagues in order to properly function and to produce the high grade baseball which the people wanted to see. ‘Negroes,’ he said, ‘no longer are willing to pay to see just any kind of ball, and least of all here in this section of the country, and where they can see Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig and other stars on regular big league teams instead. You must give them a comparative brand of ball.’ And it was his opinion that the brand of ball as played by the Pilots and the Crawfords was well worth the price of admission.”

All of those comments [at least as worded by Anderson] from Griffith reflected the latent of patronizing paternalism found among many white baseball executives, managers and players when viewing blackball. It was a verbal patting on the head and an only partially earnest, “You can do it, little guy. I know you can.”

Griffith also, perhaps unconsciously but still absolutely clearly, established Organized Baseball and its talent as the standard bearers of top-notch baseball, hinting that Negro players like Suttles and Dixon – while certainly quite talented – were still a notch below the beloved Babe.

To that end, it’s also worth noting that, while effusive in his praise and generous in his advice, Griffith refrained from any mention or even insinuation of any possible prospect of or desire for integration. For example, while he dubbed Suttles “worth anybody’s money,” he didn’t even hint that he himself would have any interest in signing the Mule – or any other African-American player.

However, given that it was 1932 and Judge Landis still held iron-fisted sway over the status, such thoughts from Griffith were probably just about as good as blackball was gonna get.

Anyway, as it was, the Pilots did eventually fade at the end of the ’32 campaign and the unceremonious demise of their league, at least as anything resembling a major Negro Leagues team. (They did manage to trudge on as an independent/semipro team for a year or two.)

Webster McDonald

The members of the Pilot roster thus scattered hither and yon. Suttles returned to the Chicago American Giants for ’33, while Nip Winters and McDonald hopped to the Philly Stars. Brewer slid on over to the KayCee Monarchs, Dunn suited up for the Black Sox and Nashville Elite Giants, and Matlock was inked by Greenlee, who continued to amass what was quickly becoming one of the greatest aggregations in Negro League history. Trent, Searcy, Eggleston and Bun Hayes also moseyed on to various squads and played out their careers to varying levels of success.

Jake Dunn

What about our good friend Ben Taylor, future Hall of Famer and East-West League umpire? His career continued for a few years more, mainly in the dugout, including managing a reconstituted Baltimore Black Sox squad in 1933. He also returned to D.C. in 1938 to manage the Washington Black Senators.

But Taylor’s later life was unfortunately not devoid of strife – in fall 1932, just as the East-West League was on its last legs, his son, 15-year-old Ben Jr., disappeared from the family home in Baltimore, prompting even two Boy Scout troops to launch a dragnet to find the lad.

However, I couldn’t immediately find out what happened with Ben Jr., disappearance, obituaries published after Ben Sr. died in early 1953 report that he was, in fact, survived by, among others, Ben Jr., so I guess it turned out OK.

Ben Sr. still had a few more rough sports, including having his right arm amputated after a bad fall at his Baltimore home.

On yet another tangeant … Like I noted way up at the top of this treatise, I’m working on an ongoing project about 1880s base ball in Charleston, which is how my interest in Ben Taylor was piqued. I’ll hopefully put up a blog post or two arising from that research, but for now, there’s just too much wrapped up in that tale to give much of a rundown here. But trust me, there’s a lot of good stuff wrapped up in that yarn.

Now, what about the Pilots’ management/ownership, the dudes with whom I previously dropped some foreshadowing about their adventures post-baseball?

Well, it wasn’t a purdy picture.

First up are Prather and Dykes … In essence, their curtain was pulled back, revealing not a tiny, blustery wizard, but instead the pair’s real business – running numbers and the ol’ racketeering. Like so many other Negro Leagues big cheeses, Dykes and Prather used their more legitimate ventures as covers for much more unseemly deeds.

In 1933, a federal grand jury indicted Dykes and Prather on charges of tax evasion, much like big-time mobsters Al Capone and Owney Madden. A lengthy report by the Norfolk New Journal and Guide in November of that year painted a seedy picture:

“In the brief span of four years, they traveled from comparative poverty to wealth as measured by their racial standard, and back again almost to their starting point.

“Almost overnight they became big shots in the number racket, operating in Washington, Baltimore, Harrisburg and other points.”

Prather, the article stated, used a middling barbershop as his initial front:

“His business was poor, but he himself had a reputation in the … underworld of being a good hustler, not adverse to making money through any avenue which presented itself.

“He has a certain amount of color. He is a good spender and a good mixer – affable and well liked. Notoriety attracts him as a flame does a moth.

“Such were his condition and qualities when the numbers craze struck Washington. He muscled in through his affability and spending and his bidding against other bankers for big books, he built up a good business.”

Prather then alleged roped in Dykes as a partner, and the duo established themselves as two of D.C.’s biggest runners. Fed by illicit numbers earnings that allegedly reached four figures a day, the pair indulged in spending sprees, chauffeured cars, yachts, race horses and real estate. The Club Prudhom was erected as their primary cover.

Alas, the bubble abruptly and painfully burst, thanks largely to the duo’s exceeding the size of their financial britches. Reported the New Journal and Guide:

“The boom days, however – even in the numbers racket – were over. A series of numbers, heavily played, hit. Their bank was unable to stand the strain. With the big commission and salaries they were paying for play, they were unable to carry on and finally reached the point where they were unable to pay off.”

After failing to stem the bleeding with some financial finagling, Prather eventually opened another (more modest) club in D.C., and Dykes started up a taxi business.

After failing to file returns on an alleged annual income of $35,000, Dykes and Prather caught a break from Fourth U.S. District Court Judge Calvin Chestnut, who fined them each $3,000, reprimanded them harshly, and issued a sentence and parole (I guess both sentences could happen at the same time) lasting three years.

The sentence was handed down in March 1934 following a four-month IRS probe that apparently included a close look at the Pilots baseball team, which figured into the duo’s smothering of attention to their illicit dealings.

To make matters worse, it seems Dykes didn’t learn his lesson – just more than a year after his tax case calmed down, Dykes was again busted, this time by the Prince George’s County cops, who raided his new hot spot in Landover, Dykes’ Club House

It seems that the club grew especially clattering during one weekend’s festivities. After neighbor complaints, the fuzz swooped in and found, among other uh-ohs, whiskey on sale sans proper license. Resulting charges on various individuals included operating a disorderly house and selling booze without documentation.

So much for Prather and Dykes. How about the fate of another Pilots honcho, Bennie Caldwell? Again, ugh.

Caldwell did immerse himself in a handful of more or less legitimate businesses – like the Crystal Caverns Club and a bowling alley – and was generally seen about town, such as at a post-fight soiree for boxing champ Henry Armstrong in fall 1940 and a similar wingding in Harlem for the great Joe Louis in summer 1946.

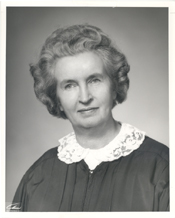

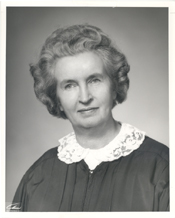

Judge Burnita Matthews

However, Caldwell, like his baseball mates, was naughty. In 1940, for example, Bennie entangled himself in a gambling and vice scandal at the Little Belmont Club in Atlantic City, and in 1954 he endured a final ignominious fate – a conviction of jury tampering in U.S. District Court. Yep, busted. Judge Burnita Matthews pasted the 50-year-old, balding, wispy Caldwell with a sentence of 20 months to five years and a $500, prompting the flustered defendant to collapse in the courtroom.

The ruling seems to have been the exclamation point on a case that began in early 1950 stemming from Caldwell’s attempts at jury bribery during a gambling case. In 1951 Caldwell was originally convicted but managed to get the verdict set aside on appeal in 1953. But his hopes of freedom were dashed at the second trial.

Oy. Between Prather, Dykes and Caldwell, the fact that yet another former Pilots owner, Roy McCoy, was sued for allegedly stiffing an investment partner in February 1932 look like miniscule potatoes.

Sooooooooo, the tale of the Washington Pilots – the franchise that knotted up numerous strings of personal research and serves as a moderately glorious Independence Day yarn from the nation’s capitol. I greatly apologize for the rambling, possibly (at times) convoluted and disjointed narrative. It’s been a loooooong time since my last post, so I s’pose I had a lot of verbiage stored up.

One final, tangential postlude, though … Sprouting off from the idea of big-time politicians courting Negro Leagues baseball fans for votes, although, as Gary noted in his blog post, there’s no evidence that a sitting president ever attended a blackball contest, in 1940 the city of Chicago came close to such a landmark occurrence when Republican presidential candidate (and fellow Indiana U. alum!) Wendell Willkie addressed a largely black crowd of 10,000 at the American Giants’ ballpark.

Wendell Willkie

The event appears to have been solely a political rally, with no actual game being played. Willkie apparently went for broke, too – one press report stated that he “frankly appealed for the understanding and support of the Negro group.”

Despite Willke’s impassioned plea at that rally, and despite every other best effort by the candidate and his running mate, Charles L. McNary, the Republican U.S. Senate minority leader from Oregon, the pair lost to FDR in the 1940 election.

Willkie, who died just four years later at the age of 52, seems to have been very similar to Charles Curtis, the vice president who threw out the first ball at a Washington Pilots game way back in 1932 – they were both well respected for the dignified comportment, valorous honesty and dedication, and passion for their cause. Many of his peers admired him despite policy differences.

So, there you go, my comeback, Fourth of July blog post. Again, I greatly apologize for the absurd length and winding narrative that probably, at times, didn’t make complete, linear sense, but, if you had the gracious patience to work through it, my deepest gratitude.

And enjoy the holiday! And to many of my SABR friends, I’ll see you in KC in a few days!