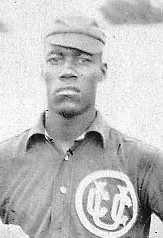

Topeka Jack Johnson

It’s weird, in 2016, to envisage the Midwest and Great Plains as “the West,” including when it comes to the sport of baseball. It’s been almost 60 years since the Dodgers and the Giants and the A’s bailed on the East Coast and headed to California, and the Pacific Coast League has existed for 113 years.

In fact, with Japan, Korea, Australia and other countries on the Pacific Rim continuing to nurture and grow their already beloved and well established baseball cultures and traditions, the concept of the West in hardball circles has been rendered almost moot.

But things were quite different way back in 1910, especially when it came to segregated African-American baseball in the middle of our then-still-expanding country. (Of course, most of that expansion occurred through war, violence and duplicity, and decimated the Native-American population and cultures, not to mention the blatantly imperialistic Mexican War. But that’s neither here nor there for the purposes of this post.)

By the end of the 19-oughts, a bunch of black baseball teams — all of them mostly barnstorming and independent aggregations — had established secure roots in the East and blossomed, making baseball a staple of African-American life on the upper Right Coast. In addition, several teams were starting to crystallize and establish stability.

What about the Midwest? There, too, existed a large handful of successful, independent and touring blackball squads in Midwestern burgs like Chicago, Kansas City and Minneapolis-St. Paul. And the frontiers of the far West? Aggregations had already popped up in Salt Lake City, Los Angeles and the Pacific Northwest.

However, nowhere in the nation were any long-lasting, stable blackball leagues that could parallel the circuits in so-called Organized Baseball. There had been a series of attempts to do so in various parts of the country, but all them invariably collapsed at the end of their first seasons — if they had even survived that long.

(That’s fully professional, multi-state leagues, however; many cities and states had local African-American semipro, industrial, sandlot and amateur loops that featured vigorous competition and solid attendance in terms of the scale of the ventures.)

Surprising, then, is the fact that many of the nation’s regional blackball circuits sprouted up — or tried to, anyway — in the Midwestern and Plains states, areas that were, in many ways, still getting their footing and prosperous permanence in terms of economies and populations that could support such a league.

True, it was Rube Foster’s seminal Negro National League — featuring mostly Midwestern teams — in 1920 that emerged as the first long-lasting black league in the country. (An East Coast-based companion loop came about in 1923 in the form of the Eastern Colored League.)

But there had been and would later be multiple other attempts at establishing a steady blackball league in the region, many of which have already been uncovered and studied by researchers.

One coagulated during the last week of December 1910 that actually stretched into the South, with more-or-less formal headquarters in the Windy City and projected franchises in Chicago, Kansas City, Louisville, NOLA, Mobile, St. Louis and Columbus.

The circuit had the hearty involvement and/or involvement of influential entrepreneurs and baseball magnates like Foster and Topeka’s Jack Johnson, who wasn’t related to the similarly named black heavyweight champion but who would become arguably the Midwest’s most passionate, proactive and expansive African-American hardball enthusiast, promoter, player and manager.

Unfortunately, the loop never really got off the ground during the ensuing, proposed 1911 season, and there doesn’t seem to have been another earnest attempt at a “Western,” i.e. to the left of the Mississippi River, until 1922 — two years after the formation of the NNL — when the nascent Western Colored League tried to get off the ground during an organizational gathering in Wichita in May of ’22.

Jack Johnson (the baseball one) was named president of that circuit, but even his enterprising leadership couldn’t secure the WCL’s survival, and the league disintegrated a short time later.

Those two aborted endeavors have probably been the two earliest, highest-profile, most well known black baseball leagues to exist — or at least attempt to exist — in the Midwestern and Plains states during the first quarter of the 20th century.

But there was another two, heretofore unknown, that tried to materialize in the summer of 1910, six months earlier than the one that tried to form in December of that year for the 1911 season.

One of the primary reasons for the 1910 circuits’ anonymity — which has lasted through today — is a seeming lack of coverage at the time of the loops’ coalescence; in fact, the best, most detailed account I could find of one of the mid-1910 leagues was in the June 10, 1910, edition of the Nashville Globe, even though that city didn’t even have an entry in the entity.

Calling the June confab “an enthusiastic meeting,” the Globe stated:

“Plans for the formation of a league, ‘The Western Colored Baseball League,’ were perfected last week at St. Louis, Mo. …

“The following cities have secured franchises in the league: Kansas City, Mo.; Kansas City, Kans.; St. Joseph, Mo.; Topeka, Kans.; St. Louis, Mo.; Springfield, Ill.; Peoria, Ill.; and Chicago.

“The officers of the league have arranged a salary limit not to exceed $1,000 per month for each club for the first year.

“It is planned to begin playing this season, and the schedule is being arranged to open June 15th or 20th. The schedule will be ready for publication sometime next week, as will the names of the managers of the eight clubs.

“Mr. [W.H.] King, the vice-president stated that two well-known St. Louis players had already been dispatched to the South to round up players for the St. Louis team.

“Negotiations are under way for players by the other managers, and as the business of the League will be ably managed, there is no reason why it should not be a financial success.”

In addition to King as VP, other circuit officials included George Washington Walden as president, David Wyatt of Chicago as secretary, and J.W. Spence of Chicago as treasurer.

Wyatt was a could have been a critical cog in the operation; as a prominent correspondent for the Indianapolis Freeman, he had the eloquence and the medium with which he could spread the word about the black baseball world and predict and hope for its future success.

In fact, in the April 16, 1910, edition of the Freeman, Wyatt published a lengthy diatribe to that effect, one that also perhaps foreshadowed the June 1910, league organizational meeting. He predicted that the 1910 campaign would be a banner year with teams like the Chicago Giants, the Leland Giants, the Philadelphia Giants, the Brooklyn Royal Giants and the Kansas City Royal Giants.

In the missive, Wyatt also asserted that African-American players and teams were the equal of any in major league baseball. However, he also urged black franchises to follow white teams’ lead in utilizing public relations and cozy ties with the media to strengthen blackballs popularity and, therefore, its financial prospects.

Wyatt wrote:

“Reports from all sections of the country have been coming in and all convey fresh information of gigantic plans under consideration of the promotion of baseball. If the many plans which have been hatched are brought to a healthy life we take it to mean that the new year of 1910 will be the banner year in Negro baseball. …

“… There is no profession which is a greater leveler of the races and there are none which will tend to mold a higher standard of moral character than our national game. …

“The class of baseball that the Negro is putting up at this time is very evidence that he is giving his moral and physical welfare the proper amount of attention. He has advanced far beyond that brand in which comedy plays the leading part, and has now captured the attention of persons in all walks of life who appreciate intelligence. These same persons have thrown down the gauntlet to all agitation of the time-worn color line and have openly declared the Negro baseball player the equal of the best and worthy of the same loyal consideration which has been shown the white players. …

“We should speedily eliminate the prevailing methods of selfishness in baseball and we should awake to the realization of the fact that the more towns and players that we can put upon the map, the better and more substantial our financial resources become. Negro baseball has been at a stagnation for years and for no other reason that the game has been confined to a select few. We at this time demand that all be given a chance and if a city or town is worthy of financial consideration it should be worthy of having their business placed in print. … Why our colored managers insist on maintaining such an amount of silence and secrecy concerning their operations and plans is part of baseball that years of experience has taught me against the wisdom of. …

“If we intend to do anything in baseball we must not be backward and dull in getting our plans before the people. Months in advance we are put in touch with the doings of big league clubs, and by the free use of the daily press their plans are heralded far and wide. These are the methods that bring success.

“By the time this letter reaches the eyes of the people we will have some definite reports on the Negro in a real contest. We sincerely hope that all clubs will have the largest and most prosperous that has ever befallen the lot of the Negro in baseball.”

However, on top of that league (and also perhaps presaged by the type of optimism for blackball espoused by Wyatt), there seems to have been another 1910 that endeavored to get off the ground, with a short account in the June 18, 1910, issue of the Leavenworth Post, with a Topeka dateline:

“Next Sunday marks the local opening of a new baseball league at League park, according to a report this morning. Arrangements have not yet definitely been made but will be announced tomorrow. The league is to be known as the Colored Central Western baseball league.

“The towns included are reported to be Omaha, Chicago, St. Louis, Kansas City, Kan., Topeka and St. Joseph [Mo.].”

The article states that St. Joseph’s W.S. Carrion was chosen president, while Tobe Smith of K.C. was tapped treasurer. Finally, Topeka Jack Johnson, whose ubiquity on the Midwest African-American baseball scene is well documented, was selected secretary.

In fact, the Post asserted that Johnson was now making his home in Kansas City, Kan., and that, “It was largely through his efforts that the league was organized.”

Neither of these distinct and valiant undertakings stuck at all, but they do, however, mark one of the earliest and previously uncovered attempts at unity and cohesion in the nebulous world of black baseball in the first couple decades of the 20th century.

In addition to the brevity of each circuit’s existence, one key, common variant running through their parallel story lines is the involvement of men from both halves of Kansas City — namely, Jack Johnson, Tobe Smith and George Washington Walden. The trio were both collectively, variously and separately responsible for two popular franchises in those twin cities circa 1910, the Kansas City Giants and the Kansas City Royal Giants.

George Washington Walden’s WWI draft card

The two franchises, and the three owners, intermingled and formed alliances at certain times, and were at other times passionately competitive as sworn enemies who played out their dramas not just on the field, but also through the media (namely, the influential Indianapolis Freeman).

The story of early-20th-century African-American baseball in KC is a complex, convoluted and fascinating saga in the years leading up to the rise of the legendary K.C. Monarchs. It’s a narrative that’s already been well researched to some extent, such as this piece is Baseball History Daily.

Also noticeable in the articles about each league is the inclusion of two cities in both entities — Topeka and St. Joseph — which raises a question of whether the squads from each city were in fact in both leagues, and, correspondingly, if the presence of the two cities in both proposed circuits are a hint that what we’re dealing with were differently reported versions of the same, i.e. only one, league.

Those pontifications remain unclear and without concrete answers, However, in my next post about the trailblazing but short-lived Western colored leagues of summer 1910, I’ll focus on those two overlapping cities — Topeka and St. Joseph — that helped create the two loops —or the one loop.