This is the third and final installment of a look into the 1945 Cleveland Buckeyes’ Negro World Series champion season. For the first post, go here, and for the second one, it’s here.

When the Cleveland Buckeyes actually did the impossible and toppled the mighty Homestead Grays in four straight contests to etch the Bucks’ name into history as the stunning victors of the 1945 Negro World Series, the Cleveland Call & Post newspaper triumphantly trumpeted that the Bucks had completed a Cinderella season with an “amazing championship.”

Fundamentally, the team’s decision to bring in a battle-hardened veteran to pilot the squad — and to harness and mould the natural talent and spirit found in the Buckeyes — might have been the most important decision team owner Ernest Wright and his management could have made. In the C&P’s Oct. 27, 1945, issue, writer Bob Williams credited the team’s talented skipper with pulling together the championship team:

“The man behind the scenes in the sensational World Series victory … was the quiet, unassuming catcher Quincy Trouppe, new manager of the Cleveland squad, whose program for the year contained the factors that spelled success and a championship.

“It was all intentionable [sic], and planned and predicted, but the person who worked it out made no fuss, and very little discussion of his program. All of [his] attention was directed towards the task of developing the team which eventually, within one season, romped through the Grays as if they were a sandlot team. …

“Trouppe’s job was a full one, playing, directing field strategy, and directing the players from the bench. On more than one occasion, he was seen to leave a position on base where he had hit safely to direct the batter, or runner on another base, what strategy to employ, and more than likely not, he was right.

“Trouppe wasn’t the most publicized or the most appreciated player on the Buckeyes by a long shot. In fact, too much of the credit for what was being done was given elsewhere. Had not this single individual been a member of the squad, it is almost a certainty that the Buckeyes would not have been in the running for the league championship this year.”

Williams asserted that Trouppe moulded the Bucks into fighting trim without fiddling too much with the roster — aside from the addition of spark plug infielder Avelino Canizares, there were few new faces in the Cleveland dugout. Williams also credited Trouppe’s magic behind the plate, especially calling for pitches, with sharpening his pitcher’s control and confidence.

But how do the Buckeyes fit into overall hardball history? Case Western Reserve University graduate student and Society for American Baseball Research member Stephanie Liscio drew a comparison between the ’45 Buckeyes’s achievement and the 2001 major-league World Series, in which the upstart Arizona Diamondbacks — whom, like the ’45 Buckeyes, used stalwart pitching as a foundation for success — skewered a previously dynastic New York Yankees team that was struggling, unsuccessfully, to retain its grasp on a title.

Liscio traced parallels between that falling Yankees squad and the declining Grays of 1945. That, she says, led, and continues to lead, pundits and historians to downplay the Bucks’ achievement that year.

But, like the ’01 Yanks, the Grays were able to mask their crumbling empire with a solid regular season, a situation that allowed the fresh-faced Cleveland squad to zoom in below the radar. Says Liscio:

“That was really the tail end of that Yankees dynasty that had a stranglehold on baseball in the second half of the 1990s. There were folks in the media in Cleveland in 1945 that thought the Buckeyes had a chance because the Grays were aging and losing a step. In many ways, the 1945 Grays and the 2001 Yankees were both powerful, talented teams, entering the back half of their dynasty, that were displaced by a young upstart.”

Still, in hindsight, nothing can take away from the achievements of the ’45 Buckeyes — achievements that, says Kent State University Professor and SABR Negro Leagues Committee member Leslie Heaphy, have only glowed more with the passing of the decades. She says:

“I’d say that the 1945 Buckeyes were a well-rounded team that managed to shut down what was a very powerful Grays offense, even if it was starting to enter its twilight. They shocked a lot of people, but maybe they shouldn’t have — there was a lot of talent there, even if it wasn’t superstar-level talent.”

There is, of course, an interesting postlude (or two) to the tale of the 1945 Cleveland Buckeyes, one that involves a need to continue making money to stay afloat —and a wee bit of controversy.

It came in the first week of October of that year, when the Buckeyes and the Grays locked horns in a pair of exhibition clashes at none other than Yankee Stadium after the World Series was over.

The Grays swept the doubleheader with identical 7-1 scores, leading fans and pundits to stew and steam over what they viewed as some as a slack performances by the vaunted Grays during the World Series. Wrote New York Amsterdam News scribe Dan Burley in the paper’s Oct. 6, 1945, issue:

“The Grays in these two [exhibition] games came definitely to life and pinned back the collective Cleveland ears … That is what made people so salty. If, they pondered, Buck Leonard, Josh Gibson and Co. could toy with Cleveland after that team had won the championship, why in the hell wasn’t such a performance put on when our money was on the line for the Homestead crew during the series?”

Daniel, watch your language!

It should be noted, perhaps, that some observers weren’t really happy with how the whole ’45 Negro Leagues season went down. None other than legendary Pittsburgh Courier scribe Wendell Smith groused in his year-end wrap up of the sportive scene:

“On the matter of organizational function, Negro baseball left itself wide open. Once again it failed to operate according to the rules and regulations of organized baseball. Its member teams played more exhibition games than league contests; players socked and battered umpires; fines were inconsistent with violations and the officials appeared to know less about penalties than ever before; the East-West [All-Star] game was a financial success, but a disappointment from the standpoint of attendance; players were traded and re-traded with abound and the fundamental rules and regulations of the spacious baseball world were ignored with brazen regularity.”

Curmudgeonly and grouchy? Perhaps. Accurate and insightful? You bet.

The 1945 Negro Leagues campaign might or might not have been a stellar one in terms of league functionality and caliber of the product put forth for the fans. There’s little doubt that the world of blackball was more willy-nilly and seat-of-your-pants when it came to what happened on the field and in the financial coffers.

The question of whether the Homestead Grays gave their all, so to speak, in the Negro World Series perhaps still remains open for debate as well. Then there’s the matter of the supposed major-league “tryouts” Buckeyes stellar outfielder Sammy Jethroe and four other promising Negro Leagues stars, including Jackie Robinson, who would be actually be signed by the Brooklyn Dodgers near the end of the year.

Sam Jethroe

So, in hindsight, the 1945 Negro Leagues season was … interesting. But regardless, the Cleveland Buckeyes achievements that year cannot be overlooked or ignored. The Bucks were a fantastic squad, one of which even the great Rube Foster might be proud.

Cleveland was scrappy, but it was also rich with talent; while it had no future Hall of Famers or what history has dubbed true superstars — Jethroe could very well be the exception, as many historians and Negro Leagues enthusiasts believe he is one of the most under-appreciated — the roster was solid from top to bottom. They knew how to clout the horsehide, but they could also play small ball — stolen bases, bunts, timely hits. Well rounded is a word that certainly comes to mind.

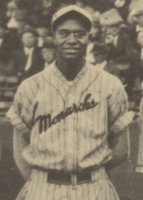

Quincy Trouppe

And that pitching crew … the whole starting rotation included four wily, skillful pitchers, all being caught by an expert catcher. And then there’s that catcher and manager, Quincy Trouppe — he brought it all together, bringing heart, smarts, experience and wisdom to a squad that was on the verge of greatness.

In fact, let’s finish this post with some thoughts from Quincy himself, via Bob Williams’ Oct. 27, 1945, Call and Post article, which included an interview with the manager. Take it away, Mr. Trouppe:

“I knew I didn’t have power hitters, with the exception of myself, so I had to utilize the speed, hit-and-run bunt and other batting techniques to the greatest possible advantage over my opposition.

“After deciding the type of strategy to employ I had to coach the players on when, how and what stage of the game to use a particular strategy.”

He added:

“When I came to the Buckeyes last year I noticed that although they were good ball players, they had missed a lot of basics, they were lacking in the fundamental knowledge of the game, they were not doing the things they should have been taught to do.

“I believe most teams in the colored leagues are sadly deficient in these fundamentals which represent the difference between a good team and a championship team. …”

Well said.

Endnote: For a deeper look at the 1945 Cleveland Buckeyes season, and every other season for the team, check out www.clevelandbuckeyesbaseball.com, operated and produced by stellar Negro Leagues and overall baseball historian Wayne Pearsall.