Bush Stadium, way back when …

Well, I’m back after a much-too-long hiatus, and I have a couple subjects upon with I’d like to expound and/or report. One is a very serious topic that I’ll try to start tackling tomorrow and over the weekend, but I’ll keep the exact nature of the subject quiet for now. I’m also going to attempt very hard to pull together updates on the situations of both Ducky Davenport here in NOLA and Alexander Albritton in Philly.

But today, a much lighter, even quirky story of a young white Indianapolis teenager combing through a crowd of nothing but black faces …

A couple weeks ago, Chris Rickett, an old friend from my college days at the Indiana Daily Student — he and I, in fact, are bonded by an unforgettable incident that should be well known to those who read this who were in the IDS at the time — messaged me on Facebook and told me about his step father, Phil Nolting.

Phil, as it turns out, spent several summers while a teenage student at Indianapolis’ Arsenal Tech High School in the early 1950s trudging up and down the steep stairs at Indy’s old Bush Stadium, hawking peanuts, Cracker Jack — singular, people, not the plural Jacks! — and beer during baseball season.

Most of the time, Mr. Nolting criss-crossed the stadium aisles at Indianapolis Indians games, when the city’s longstanding minor-league franchise in Organized Baseball did their thing on many a sultry central Indiana night 60-plus years go.

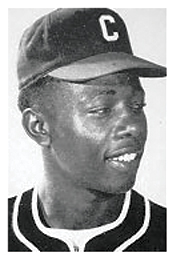

But, Nolting says, when the Indians were out of town on a road trip, Bush Stadium would play host to what has, in historical hindsight, become the city’s most famed hardball team — the Indianapolis Clowns on the Negro Leagues.

And young Phil, along with his brother and a handful of other pals from Arsenal Tech, would ply his adolescent trade for the Funmakers’ home games — that is, when the Clowns weren’t barnstorming like mad for much of the season.

It was, to say the least, an interesting situation for Nolting.

“My and my brother used to joke that we were the only white people out there,” Phil says.

That’s because the first couple years of the 1950s were a very, very heady time in Indianapolis, including when it came to race relations. As Phil noted to me, “Integration was just starting to take place.”

Athletically, Indiana has always been, of course, a basketball-first state, and the early 1950s were huge years in Indianapolis in that regard. This was the era of the famed “Milan Miracle” (the true story on which the movie “Hoosiers” is based), but that was followed by an even more culturally and racially significant event — the hoops team from Indy’s Crispus Attucks High School, led by the Big O, the incomparable Oscar Robertson, became the first all-African-American team to capture the state championship.

That was a watershed moment for sports and race relations in a state that just a quarter-century before had played host to the national KKK headquarters and whose government was quite literally in the hands of the Klan — they were everywhere in Indiana.

And, with the crucial Brown v. Board Supreme Court ruling on segregation still a couple years away, Indianapolis, at the time, could be viewed as walking a tenuous line between being a geographically Northern State but, it many ways, a culturally and socially Southern State.

Into this mix came the Indianapolis Clowns, who weren’t the city’s first great Negro Leagues team — that distinction, aside from squads in the 19th century, would go to the ABCs — but probably its most famous, thanks to their on-field antics and, well, clowning, which mixed extremely well with their genuine hardball acumen.

The Clowns were so good and, therefore, so popular, that Phil Nolting says the Funmakers routinely outdrew the Indians of “Organized Baseball” when they did manage to convene home games at Bush Stadium.

“Back then, the Clowns brought bigger crowds than the Indians,” Phil says. “The stadium was full. The Clowns were really popular, as I recall.”

But, he added, “It was an all-black crowd.”

Which made for a few jarring, or at least unusual, experiences for the white teenager from Arsenal Tech and his buddies roaming the crowd as vendors. But for the most part, things went smoothly for both the kids and the fans.

“We had our problems,” he said, “but really it was fun. This is when integration was still going on, but we never had any problems.”

And because Indianapolis is famous for something else — its auto racing, its 500 and its Brickyard — Nolting says he and his peers would work the crowds at car races, including the Indy 500, then hike down to Bush Stadium that evening for an Indians or Clowns game.

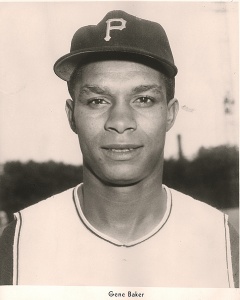

Also significant to Nolting’s tenure as a popcorn and Jack hawker — even though neither he nor many people in the stands knew at the time — was that it coincided with the arrival to the Clowns’ roster of a baby-faced youngster from Alabama named Henry Aaron.

Phil says he vaguely remembers Aaron’s name being on the roster cards and announced over the loudspeakers, but Nolting was too busy selling his product — which involved having his back to the field much of the time — to pay close attention to the future Major League home run king, or any of the players, for that matter, on both the Clowns and the Indians. That includes the times Satchel Paige, for example, made a stop at Bush Stadium to pitch.

“It’s a shame we didn’t really know who the players were,” Phil says. “You hear a lot about them now, but back then we were working. We couldn’t really see or know who they were.”

As the years have gone by, and as Phil and his buddies reflect on their Bush Stadium experiences — including being thiiiiiiiiis close to Hank Aaron — they do regret a bit the fact that they couldn’t attention more to the games and players themselves.

But he says one of his friends as since become an avid reader of baseball history, including the Negro Leagues, and he and Nolting conversed quite frequently about their rich experiences.

“My buddy and I from back then, we’d talk often about it,” Phil says. He reads a lot about the Negro Leagues, because its become quite a popular topic to study.”

It certainly has.