Here’s an obituary article on Herb Simpson for the Web site on New Orleans station WWL:

Uncategorized

Terrible news

I just heard that my friend and former Negro Leaguer Herb Simpson died on Tuesday. Right now I’m suffering from shell shock. I’m trying to gather more information right now, and I’ll post it when I can. For now, here’s a very personal article I wrote about Herb this summer. Please keep his family and friends in your thoughts and prayers.

Henry Presswood and “Bloody Kemper”

Apparently I hadn’t discovered the entirety of the picture when I wrote about the late Henry Presswood’s hometown of Electric Mills, Miss., in this recent post.

For that post, I did a little researching about the town itself and the significant and unique place it holds not just in Southern history, but American history.

What I didn’t think to examine at the time was the county in which Electric Mills — which effectively became a ghost town decades ago — sits. So when I searched for “Electric Mills” in some databases, up popped an article from the March 28, 1935, Philadelphia Tribune that contains reportage about the former town. Here’s the headline:

“Judge Lynch Presides: A Night in Bloody Kemper County, Mississippi.”

To stress the subject of the article, “Judge Lynch Presides” is spelled out in cursive writing made to look like rope — the type of rope used in hundreds of lynchings of black men and women throughout the entire country for decades, if not centuries.

That’s because the article is about the brutal mob beating of three African-American men in Kemper County named Yank Ellington, Ed Brown and Henry Shields. The trio were physically accosted and assaulted until they confessed to “their crime” — the March 1934 murder of a well known white planter.

Unlike many other similar examples of mob violence, the lives of these three men were spared because the local DA — and future U.S. Senator — John C. Stennis swiftly brought the three to trial six days after the killing in an effort to prevent the hoards of enraged white citizens — including officers of the “law” — from completing their task, dragging the three out of the county jail and killing them.

Of course, the trial proved to be a complete sham, a kangaroo court that ended with quickly and mercilessly imposed death sentences for all three. The proceedings led to an influential court case that overturned the convictions and sentences of the three men and effectively (if my interpretation is correct) outlawed the use of coerced confessions at trial and addressed the frequent lawlessness of the law enforcement community itself.

So Stennis may have conducted a kangaroo court — which was standard practice for black defendants during Jim Crow — he at least saved the lives of the three men by realizing that they would be murdered if he didn’t act quickly by bringing them to trial, decision that eventually led to that crucial U.S. Supreme Court ruling, Brown v. Mississippi.

I digress from the history lesson and head back to the Philadelphia Tribune article. The year-later reporting repeatedly refers to Kemper County — the birthplace and home of Negro Leaguer Henry Presswood, who passed away two weeks ago — as “Bloody Kemper.” Here’s one example from the article:

“Yank Ellington was seized by the mob, said to have been led by the sheriff of Bloody Kemper, on the night of the discovery of the murder of Raymond Stewart [the white planter]. …”

And:

“It may be that at the time this is being read that Yank will be dead — which will be just what the mob wishes to happen to him, since they are greatly angered at being deprived of the opportunity to have made eighth day of February a Roman holiday in Bloody Kemper.

“Poor Yank was the chief actor in the grim tragedy which occurred in Bloody Kemper just a year ago.

“Yank played a leading role and performed to a crowded house the night of his first appearance in the historic pages upon which have been inscribed the great number of brutal murders that have been committed in that county for more than 50 years.”

Thus it was common knowledge among African Americans in Mississippi and beyond that Kemper County — the ancestral home of Henry Presswood — was a cradle of white supremacist, mob violence. And in truth, that reputation most likely permeated the white community as well, at least tacitly.

According to the America’s Black Holocaust Museum, seven lynchings occurred in Kemper County between 1909 and 1930, including the death of a woman, Holly White, in September 1930 in the town of Scooba. The museum’s Web site lists five of those victims as “unknown Negroes.”

The appellation “Bloody Kemper” wasn’t just a journalistic termed coined for dramatic effect, either. In an interview conducted for the Civil Rights Documentation Project in 1999 and housed in the Tougaloo College Archives, Kemper County native and community activist Obie Clark, Clark describes his home county’s reputation in stark language:

“And I used the fact that when we were growing up, up in Kemper County, it was known as Bloody Kemper. We knew it as Bloody Kemper. Now there is a book, some white editor or publisher has published a book called Bloody Kemper, but it is not about what we called Bloody Kemper. It was about two white families feuding against each other. But we called it Bloody Kemper because of violence committed against black folks–lynchings and hangings and all.

“Our parents told us about that, people they knew. And so when we got to be teenagers, Mr. John Long, who owned the cotton gin, who owned the general store, and he owned the grist mill, and he owned the moonshine, you know the still that made whiskey. You know, he owned all those things.

“And our parents, when we got to be teenagers, our parents called us in and told us that it was time that we started calling Mr. Ben, Mr. John Long’s children, who were along our age, that we start calling them ‘Mister,’ and ‘Miss.’ And they told us always, they taught us, said, “If you go to the store, and the general store is closed, don’t go to the front door to get their attention. You be sure you go to the back door.” They taught us how to be second-class citizens.”

It was in this atmosphere that late African-American baseball player Henry Presswood was born in 1921. His parents, Dee and Josephine Presswood, were born in 1893 and 1892, respectively. Both of them had ancestral roots in Alabama, and Dee was, like most of Electric Mills, a worker at the famed electric saw mill that was the town’s sole reason for existence.

Young Henry later joined his father in employment at the facility. Josephine Presswood appears to have died sometime during Henry’s childhood; the 1940 U.S. Census lists Dee as widowed.

In both the 1930 and 1940 Census, the Presswoods lived in almost entirely African-American neighborhoods in Electric Mills, not surprising at all in Jim Crow.

In his later years, Henry Presswood served as an ambassador for the memory of the Negro Leagues and, through his yarns, helped heighten public knowledge about black baseball.

One of Henry’s favorite stories to tell was how and why he came to become a big-time baseball player with the Cleveland Buckeyes — he accepted the invitation of an old friend and teammate who had preceded him to the top-shelf Negro Leagues. As Mr. Presswood told journalist Nick Diunte in 2010:

“Willie Grace went to the Buckeyes and he was the one who told them about me. He was from Laurel, Mississippi. One day I was working and who was at my job, Grace and the foreman! He asked me about going, and I wanted to go you know. … I said, ‘What in the world are you doing here, I thought you were with the Buckeyes?’ He said, ‘I am with the Buckeyes, but I told them about you. I came after you.’ I was really surprised. I accepted and went on up there.”

That story unfolded in the late 1940s, and Henry Presswood no doubt jumped at the opportunity presented to him by Grace because Henry loved baseball and felt grateful to be given the opportunity to play the sport for a living.

But you have to imagine that, at least in the back of his mind, Mr. Presswood was also, in some ways, extremely glad to be leaving a county known to black residents as “Bloody Kemper.” Any opportunity to leave such a violent, unjust, deadly setting had to have been appealing.

But if that was the case, it seems like Henry Presswood never talked about it with the public in his later years. He never really discussed the societal, cultural, legal and political context of his roots and upbringing, which certainly wasn’t uncommon for aging Negro Leaguers, many of who — like many African-American citizens of Southern origin — didn’t want to revisit such a terrible era and setting.

Henry Presswood might have been content to let sleeping dogs lie, to not reopen old wounds, in his later years. The prospect of doing so might have simply been too painful.

But perhaps Henry Presswood never discussed things like “Bloody Kemper,” even reluctantly and quietly, because he was rarely actually asked about it. Maybe he never revealed that history because fans and journalists never inquired about it, never considered the context of Henry’s youth when meeting and interviewing him.

Such a situation could reflect a pair of modern realities when it comes to the public and African-American history. One, many younger generations of Americans simply aren’t aware or educated about how horrifyingly oppressive Jim Crow actually was. Younger citizens, of all races and ethnic backgrounds, experience a disconnect from historical reality because of ignorance at best and, at worst, an unwillingness to “go there.” We simply don’t want to hear about it.

The second reality Mr. Presswood’s story reveals is that amongst sports fans and sports journalists — even ones who love the Negro Leagues and are of aware of and deplore the injustice of baseball segregation — often never even realize or, worse, comprehend that there’s a larger world, a greater existence beyond a simple game, outside of merely sport. Quite ironically, and tragically, we still experience mental and journalistic segregation — the sports pages are about sports only, and everything else remains relegated to the “news” sections of newspapers, magazines, Web sites or TV broadcasts. Sports are fun, and let’s just leave it at that, we tell ourselves.

And I will swiftly state here that I am certainly guilty of this sin of omission and compartmentalization. I’ve really never asked my New Orleans friend and former Negro Leaguer Herb Simpson about what it was like growing up here, in the deep South, never probed his memories for such unpleasantness.

Why do I do this, or rather, not do it? One, because it shamefully never occurs to me; I’m too giddy looking at all his baseball memorabilia in his home in the Algiers section of NOLA. And two? Maybe because I don’t want to make Herb discuss such subjects, because I fear that it might force him to revisit possible traumas of his youth.

How did Henry Presswood feel about his youth in “Bloody Kemper”? We may never truly know for sure. But ask any of his Southern black contemporaries and products of Jim Crow, the numbers of whom are rapidly thinning and dwindling as time advances, the “hard questions,” and you might not like what you hear — any more than the person likes reliving a shameful American past.

It’s painful just to think about these modern realities. And that in itself is tragic.

‘He was a manager first and foremost’

I’m working on an article for Acadiana Profile magazine about Napoleonville, La., native Winfield Welch, a longtime Negro League manager who won a couple NNL titles with the Birmingham Black Barons after earning his spikes on the sandlots and ballparks of New Orleans and other Pelican State cities.

As part of my efforts, I interviewed Dr. Layton Revel of the Center for Negro Leagues Baseball Research and one of the preeminent experts on black baseball in the South and Alabama in particular. Dr. Revel offered me intriguing insights into the impact Welch had on African-American baseball.

Welch, Dr. Revel said, was something of an anomaly in blackball; while many of the black managers who had come before Welch — from Sol White on down, with Rube Foster being the blueprint — had been successful players and often player/managers, Welch was the first great African-American skipper who lacked a star-powered playing career. As such, Revel said, Welch sort of broke the mould when it came to finding quality managers in the Negro Leagues.

True, Welch did start his tenure on the diamond as a club and semipro player — what baseball figure of the early 20th century didn’t? — especially in NOLA, he was a marginal player at best who lacked the talent to earn a dependable, everyday place in a lineup or on the field. (I go into Welch’s playing days in N’Awlins a little bit here and here.)

Instead, Dr. Revel stated, Welch’s hardball talent was his acumen for eyeing and developing talent, especially in the South and particularly the deep South:

“The impressive thing about him was that he knew baseball, and he knew brilliant baseball, and he knew how to recognize a ballplayer. He knew how to scout and sign players. When he was putting together his team, he knew what he was looking for, much like Rube Foster.”

Welch also — retread cliché ahead — knew how to get the most out of his team. While his Black Barons teams of the mid-1940s might not have been been studded with superstars, he shaped his lineup into a group of dedicated, committed role players who fit together like a perfect puzzle.

“He knew how to manage a team on the field,” Dr. Revel said. “He found a way to win. He knew the science of baseball.”

Welch was like Foster in another way as well — he became a master at “small ball,” foregoing slugging for game management, speed, aggressiveness and smarts.

And because he possessed such abilities as a locator and groomer of talent, Welch accomplished what no one before him really ever did, said Revel: “He brought championship baseball back to Birmingham. He kind of set the stage for a time of prosperity for the Birmingham Black Barons.”

This is what it boils down to, said Revel:

“He’s probably the best Negro Leagues manager that no one’s ever heard of. Flat out, he was one of the best managers in the Negro Leagues.”

What I hope to show in my Acadiana Profile article is how Welch especially kept a pipeline of talent open from New Orleans to Birmingham and beyond. Welch brought so many great players from the Pelican State to the big time.

In the process, Revel said, Welch deflected the praise and recognition for his teams’ successes from himself onto his players. He was content to stay back and watch his masterful creation shine. Said the doctor: “His players and team got the notoriety, not him.”

Thus, concluded Dr. Revel: “He was a manager first and foremost.”

Henry Presswood, 1921-2014

Like just about every man (and woman) who played or managed in the Negro Leagues, Henry Presswood did what he did for one main, simple reason — a passion for the American pastime.

“It really excited me because I loved the game and they said I could play!” Mr. Presswood giddily told the South Bend Tribune in 2011. “I just did the best I could.”

At 93 years old, Mr. Presswood was one of the last remaining living links to the Negro Leagues, one of the dwindling few who could personally recall how much of their lives and souls they and their peers devoted to the game.

But a few days after Christmas — just about a week or so ago, the exact day is unclear — the baseball world lost one of those links when Mr. Presswood died in Chicago. According to reports, a memorial service is slated for today (Saturday) in the Windy City.

Leslie Heaphy, one of my friends and mentors in the world of Negro Leagues research and writing and a leader of SABR’s Negro Leagues committee, told me by email a couple days ago that while she wasn’t close friends with Mr. Presswood, she knew what he meant to hardball history.

“I did not know him extremely well but had met him on numerous occasions and presented with him once in Chicago,” Leslie said. “He was always a gentleman, quiet and courteous and loved life. He was a good player, not a star but a solid team player.”

She added that Mr. Presswood’s death represents “a sad loss because his passing represents one more loss to the fading Negro League history. He was so good at telling people about the years he played, and each time we lose a voice, the story seems to get harder to tell. He lived to tell people about his experiences.”

Mr. Presswood reached the black baseball big time in the late 1940s, just as segregation in the American pastime was crumbling and the Negro Leagues were transitioning into a type of feeder system for organized baseball. He competed for the Cleveland Buckeyes in 1948-1950 and briefly for the Kansas City Monarchs a couple years later.

Mr. Presswood first flew into blackball’s big-time radar early in 1948, when the Buckeyes started eyeing him for a possible slot at shortstop, which the Cleveland Call and Post said would be the subject of spirited competition for the starting job that year. But Mr. Presswood, the paper stated in January 1948, was near the top of the list.

“Among the short stop contenders going to the Hot Springs training camp in March [is] Henry ‘Schoolboy’ Presswood, [of] Canton, Ohio. A right hander, batting and throwing, Presswood has played with the Canton City League, in the army, and with a number of southern teams. He is 26 years old, 5 feet 10 inches, 150 pounds and a native of Birmingham.”

Mr. Presswood eventually nabbed the starting job, and while he never became a superstar in the Negro Leagues, he quickly proved his worth as a spunky little spark plug.

“Henry Presswood, a Mississippi lad,” wrote the Call and Post in June 1948, “is shining bright at short and has been hitting well.”

You’ll probably notice a few discrepancies in those quotes (not counting the violations of Associated Press style at which modern newspaper journalists would quiver). That’s OK, because in March 1950, the Call and Post somehow shaved five years off Mr. Presswood’s age and engaged in some geographical rejiggering, calling him “a shortstop … from Canton, Mississippi and …23 years old.”

Let’s clear a few things up. Mr. Presswood was born Oct. 7, 1921, in Electric Mills, Miss., not Birmingham or Canton, Ohio. And when the January 1948 Call and Post article said Canton, they likely goofed and meant Canton, Mississippi, where Mr. Presswood had played semipro ball for the Denkman All-Stars from 1938-44 before being spotted by Cleveland Buckeye scouts.

Mr. Presswood was the second child of Dee and Josephine Presswood, both Alabama natives who who eventually moved to Mississippi on State Highway 45 in the Kemper County community of Electric Mills, which was a de facto property of the Sumter Lumber Company.

The Sumter sawmill in Electric Mills

The company made Electric Mills famous — not to mention spectacularly bright, for the times — by constructing one of the country’s first sawmills powered completely by electricity. Hence, naturally, the town’s name.

Dee Presswood was, like pretty much all of Electric Mills’ male residents, a laborer at the Sumter facility. He also became a single parent when Josephine passed away in the 1930s. Henry Presswood soon joined his father as an employee of the sawmill, and in his time off, the younger Presswood played baseball for the semipro Mill City Jitterbugs after completing two years of high school.

Dark times came to Electric Mills in 1941, when the Sumter corporation shuttered its mill there in 1941, and the community quickly devolved into little more than a ghost town, a status that remains to this day.

(I’m hoping to write a little more about Henry Presswood’s Mississippi roots sometime next week.)

In February 1945, young Henry — at the time he was 23 years old — enlisted in the Army in the waning days of World War II, becoming a private and serving, according to the Web site baseballinwartime.com, for roughly two years.

Married to his wife, Thelma, Henry was discharged from the Army and briefly returned to the semipro Denkman team before hitching on with the Negro American League’s Buckeyes and later, briefly in 1952, with the famed Kansas City Monarchs.

Henry and Thelma settled in Chicago, where he worked at the Inland Steel Company for more than 30 years and played fast-pitch softball for the company team before retiring. (Inland Steel shut down in 1998.)

In his later years, Mr. Presswood became a spokesperson for the Negro Leagues, attending numerous events and regaling hundreds of baseball fans and hardball history enthusiasts with tales and remembrances of his playing days. His death a huge loss to the Negro Leagues community and to the history of the American pastime itself.

Fifteen years ago, Mr. Presswood was interviewed for the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum’s Legacy 2000 Players’ Reunion Alumni Book, in which he summed up his tenure in African-American baseball’s big time.

“I was very excited to play baseball in the league …,” he said. “I didn’t let my skippers in Cleveland or in Kansas City down.”

Those Lincoln Giants …

Up until this point, I’ve considered the mid-1930s Pittsburgh Crawfords to be the best African-American baseball team — not to mention the best baseball team anywhere, anytime, period — in history. But as I do more research into the life of Dick Redding (with assists from Gary Ashwill and others), I’m coming around to the notion that the Lincoln Giants of the 1910s is certainly a contender for the title. Thoughts?

New West Coast blog

A couple quick posts to start off the new year …

Here‘s a cool new blog by my friend Ron Auther about the Negro Leagues on the West Coast. He has personal ties to the scene in the Bay Area, so he has some pretty neat insights into the hidden and underrated blackball scene on the left coast. he’s also not afraid of speaking his mind and tossing up some “controversial” proposals and thoughts. He’s new to SABR and so far enjoying his pursuits. Check him out!

Barrow in Baltimore

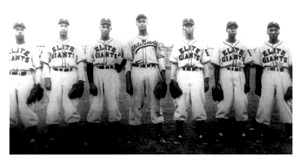

A version of the Baltimore Elite Giants

Gretna City Councilman Milton Crosby and I are taking a break for the holidays regarding a grave marker for Big Easy Negro Leagues great Wesley “Skipper” Barrow. However, I’m working on turning out a long-ish piece on him for a new New Orleans literary magazine, so I thought I’d focus a post on what was arguably the “peak” of his career, at least on a national scale — managing the 1947 Baltimore Elite Giants …

When Wesley Barrow was tapped to replace ousted Elite Giants manager Felton Snow, Barrow was still in his mid-to-late-40s who had managed Southern “minor league” teams like the Nashville Cubs and his hometown Algiers Giants and New Orleans Black Pelicans. Barrow, who also had served as a coach for the NAL Cleveland Buckeyes for a bit, had more a quarter-century of hardball experience under his belt.

However, his hiring by the Elites — whose most prominent player earlier in the decade had been Hall of Fame catcher Roy Campanella — to replace a veteran hand like Snow raised a few eyebrows. Stated the Jan. 25, 1947, Pittsburgh Courier:

“Barrow, though practically unknown in Eastern baseball circles, has played with and served as manager of several teams in the deep South. …”

The paper also asserted that Barrow was brought on by Baltimore to improve the club’s performance somewhat significantly, stating that the Elite Giants were putting into place an “overall plan for building a pennant contender in 1947.”

The Courier added about Barrow and the team:

“To help get himself off on the right foot the new field boss has prevailed upon Tom Wilson and Vernon Green, team moguls, to sign five players he has recommended.”

That quintet included for NOLA-area natives Barrow new well from the Big Easy sandlots and ballparks — Bob Bissant, Joe Wiley, Joe Spencer and Gene Hardin — the latter who had just played under Barrow in 1946 with the Portland Rosebuds of the short-lived West Coast Negro Baseball League.

Wilson and Green also promised to sign other players and trade and deal freely with other squads to improve the Elites. The execs followed that up by hiring George Scales as a field coach to help Barrow, both of whom were, stated wire writer Dick Powell, “moulding what they predict will be the team to beat for 1947 NNL pennant honors.”

Tom Wilson

The Elites ’47 campaign began with a barnstorming trip across the South with the Negro Southern League‘s Atlanta Black Crackers, whose manager, Sammy Haynes, dueled strategically with Barrow across their aggregations’ journeys. The NSL, naturally, was a step below the NNL, but the April 27, 1947, Atlanta Daily World still hyped up an impending double-tilt between the squads in Atlanta, calling the ‘header “the game[s] that Atlanta sports fans have been waiting for” and predicted the event would draw “[t]he largest crowd ever to witness a baseball game in the Gate City …” (Sports pages from bygone days were a little bit hyperbolic.)

But trouble started brewing immediately, or so Hall of Fame Baltimore Afro-American sports columnist Sam Lacy wrote on May 3:

“Report that Wesley Barrow, newly-appointed Baltimore Elite Giant manager, has been fired, was denied this week by the club’s front office.”

In fact, Lacy continued to view Barrow with a jaundiced eye throughout the season; in the May 17, 1947, issue of the Afro-American, the scribe asserted that Barrow “looked decided amateurish when he yanked Second Baseman Junior [Gilliam] from last week’s game against Newark immediately after the young infielder had committed an error afield.”

Sam Lacy

Lacy, then, must have been positively giddy when the ax eventually did fall on Barrow midway through the season, a development that even a two-game sweep over the storied Homestead Grays in late May couldn’t forestall. The writing might have been on the wall for all parties concerned when Green fined Barrow in early June because players Amos Watson and Butch Davis lollygagged on grounders.

The Aug. 2 edition of the Afro-American broke the news of Barrow’s ousting by calling him the “Elites’ deposed manager” in a cover of the Giants’ 6-5 win over Birmingham. Scales, by then, had been promoted to “acting manager.”

Apparently up until that point, the Elites had been streaky and underperforming as of late, stated the Aug. 23, 1947, Atlanta Daily World:

“The Baltimore Elites who were once showing signs at a real superiority stumbled for a while, fired their manager, Wesley Barrow, shook up the team to get back into the running [in the NNL] and refuse to be counted out.”

It seems that Snow was brought back in to finish the ’47 NNL campaign for Baltimore, or so reported Lacy in January 1948; perhaps needless to say, the Elites hadn’t claimed the 1947 league pennant.

The Taylor brothers

Baltimore’s manager merry-go-round didn’t stop there; in late January of ’48, Candy Jim Taylor, veteran pilot and part of blackball’s royal family, the Taylors, had been hired to bump out Snow. Jim Taylor had just been canned by the Chicago American Giants of the NAL after guiding that team for three years. In a January 1948 article in the Afro-American, Green was quoted as saying, “In any event, you can be sure we will be aiming to strengthen the club.”

So ended arguably the zenith of NOLA legend Wesley Barrow’s career on the national stage. It had been agonizingly brief and, apparently, very volatile from the start. Why Wilson and Green hired Barrow in the first place, then, seems to be something of a mystery, especially because the latter’s stay with the Elites appears to have been destined to fail and was sandwiched between two tenures by Snow as the club’s manager.

But it didn’t phase Barrow, who forged ahead in his managerial career, which lasted practically up until his death on Christmas Eve 1965. It also didn’t dim the love Skipper continued to feel from New Orleans blackball fans and players. He was, and is to this day, still a legend.

Conflageratin’ and recollectin’

Got this from my colleague and online mentor Gary Ashwill a couple days ago — it kind of encompasses several of my recent posts about Dick Redding and Cuba. It seems like Cannonball conflated some of his memories when he was interviewed for the 1932 article I described late last week about pitching against the Tigers in Cuba.

Such exaggeration is common in the Negro Leagues, where record-keeping definitely wasn’t as detailed or diligent as it was in “organized baseball.” However, such foggy yarn-spinning certainly wasn’t limited to black baseball or Cuban players — white players were absolutely known for doing it to. Perhaps we can call it the “glory days” syndrome.

Anyway, here’s Gary’s thoughts:

Hate to be the bearer of bad news, but Dick Redding didn’t no-hit the Detroit Tigers in Cuba — in fact he never played against them there. The Tigers only made two trips to Cuba, in 1909 and 1910, before Redding had entered big-time baseball. On November 18, 1909, Eustaquio Pedroso of Almendares pitched an 11-inning no-hitter against the Tigers. The Tigers’ trips to Cuba were very well-covered, both in Cuba and the U.S., and Pedroso’s no-hitter was pretty well-known at the time.

The 1932 Defender piece is interesting, and probably the source for several factoids that get repeated a lot (for example, Redding’s supposed 43-12 record in 1912 along with 17 no-hitters). Unfortunately it’s full of exaggeration, though the exaggeration is sometimes based in fact. For example, he didn’t no-hit Jersey City of the Eastern League in 1912–but Redding and the Lincoln Giants did beat a barnstorming team with several Jersey City players (along with players from other EL teams) 3 times at the end of 1911, including winning a doubleheader. Two of the victories were over Jack Doscher (probably the “Dozier” of the Defender article); one of them was a 1-0 win, Redding striking out 12.

In 1912 he definitely pitched at least two no-hitters, one against José Méndez and the Cuban Stars in Atlantic City, the other a perfect game (with 14 Ks) against a team called the “Cherokee Indians.” He also defeated Al Schacht and the “All-Leaguers” (a team of players from the Washington U.S. League team and a semipro team called the Metropolitans), striking out no fewer than *24* batters (but giving up 3 hits). In the 1932 article Redding mentions Schacht as a Jersey City player in 1912. He did pitch for JC, but not until 1919. Could be that Redding was conflating some of his memories.

In my opinion, it’s perfectly possible that he pitched batting practice against the NY Giants at some point. In 1911, for example, the Giants played a series against the (white) Atlanta Crackers on their way north, and Redding was later said to have pitched batting practice for the Crackers (see Atlanta Daily World article from 1934, attached). I kind of doubt McGraw brought him north, though. The Giants’ spring training was pretty well-covered by the press, and I’d think the presence of a black pitcher, even just as a BP thrower, would have been worth a few news items here and there.

Also, I have to note that my Rochester bud, Mike Sorenson, pointed out, quite correctly, that the Tigers hadn’t won the World Series in 1912, as Redding “recalls” in the 1932 Defender article. Detroit went to the Series in 1907, ’08 and ’09 and lost ’em all, and they didn’t even go in 1912, let alone win. (The Red Sox defeated the Giants that year.)

A showdown of Georgians?

A small part of the Cannonball Dick Redding mythology/hagiography is that the famous (or infamous, perhaps) Ty Cobb refused to take batting practice from a Redding, a blossoming speedball artist and future Negro League great from Atlanta.

Since both Cobb and Redding hailed from Georgia, it certainly could be feasible for such a showdown — or lack of a showdown — to take place. Tracking down the possible veracity of the story, however, has proven very difficult.

It seems to have first come to life in a relatively early, and relatively brief, biography of Redding by influential Negro Leagues historian John Holway. In the piece, written for the Society of American Baseball Research, Holway interviews several of Redding’s African-American contemporaries, teammates and opponents, who regaled the writer with tales of Redding’s mastery over all hitters, black and white.

Fairly early along in the bio, Holway writes this: “Dick was so good that his fellow Georgian, Ty Cobb, reportedly refused to hit against him in batting practice.”

But despite Holway’s very thorough, lively and enlightening interviews with the former players, the author doesn’t directly attribute the above quoted statement to any one of the athletes he talked to for his article, or any other source for that matter.

I did a little database digging, as well as quickly reviewed various Cobb biographies — and there’s a lot of them — and found no references to any direct pitcher-batter confrontation between the two hardball greats, certainly none that went down in batting practice as Holway described. Granted, I was unable to go into extremely extensive depth in this pursuit, but so far, I’ve found no conclusive evidence that Cobb spited the Cannonball.

However, that certainly doesn’t mean the pair never crossed (base)paths. I discovered the above article from the Dec, 10, 1932, Chicago Defender. The article is an absolute revelation, and a gem of a tale. Why? Because it features Redding himself directly detailing an encounter with Cobb and the Tigers. It’s fantastic.

The article, written by A.E. White, is basically one huge direct quote from the Cannonball. Toward the end, Redding says this:

“We used to play the big leagues down in Cuba during the winter. I remember pitching a no-hit game against the Detroit Tigers, hooking up with George Mullins in that battle. Remember Mullins? I also pitched against the late Wild Bill Donovan, later manager of the New York Yankees. What we used to do to Ty Cobb in those games was a-plenty. We just kept him off the bases to make him sore. And you haven’t seen a man sore until you see Ty Cobb raving mad because he couldn’t hit the ball safely. Incidentally, they were the world’s champions at the time.”

That was in 1912. But there definitely could have been an earlier fracas between Cobb and Redding, back when Redding was in all likelihood still a semipro hurler on the ATL sandlots. (However, as a side note, while some historians assert that one of the sandlot teams for which Cannonball played was the Atlanta Deppens, I’ve again had trouble confirming that, even though the Deppens were a fairly long-running and successful semipro club.)

In the mid-to-late 19-oughts, the Tigers help spring training at various cities in Georgia, enterprises that often included exhibition games in at Atlanta or against Atlanta-based aggregations. Were any of those contests against any sort of African-American team? It’s not immediately clear, but it’s hard to imagine that there wouldn’t be at least a couple like that.

And it’s not like the media, baseball fans and Georgia residents weren’t aware of the likelihood that it would happen, or at least that the Tigers would encounter a fair amount of black citizens during their spring-training treks across the state of Georgia. Take this from an April 1, 1906, dispatch the the Detroit Free Press by writer Joe Jackson:

“One section of the Southern population always has its welcome warm for the baseballist. The colored odd jobs man is there strong with the City-of-Welcome stuff on all occasions. Ever our Afro-American friend has his eye out for the visitor from the North, who tips more often and more stronger than his Southern cousin, and who doesn’t get one-half of efficient service as the latter, as has well been brought out by divers [sic] occasions by Tyrus Cobb. The latter, born and bred in the South, knows the ways of the Negro perfectly, and is ever ready to prove that the colored man more readily responds to the requests or demands of those in the South, who maintain the old relation of master and man between the races, than to those of the Northerner, who proceeds on lines that indicate that he believes the fourteenth amendment means just what it says.”

It’s hard (at least for me) to fully grasp the tone of the paragraph. Is it sarcastic? Is it patronizing? Paternalistic? Tongue-in-cheek? Snarky? Or completely straight-faced (and rather clueless)?

At the very least, it’s quite intriguing, especially given the racial dynamics of the time and Cobb’s notorious (though recently disputed by some) racist reputation. But it also raises a valid point: in many ways, Southern whites were less hesitant about interacting with blacks, with whom contact was frequent, than white Northerners, who, despite allegedly progressive beliefs, were often reluctant to relate to African Americans and shunned them because Northerners weren’t as used to being around minorities.

In fact, that situation still exists, to a certain point. While Southern and Northern racism might take on different forms and subtleties, at the core they could very well be the same.

But I digress. So did Tyrus Cobb refuse to take BP from Richard Redding Jr.? Dunno. Could it very well have happened? You bet. Will we ever know for sure? Probably not. As a result, the tale will continue to be enshrined in baseball lore as a juicy what-if and what-could-have-been.