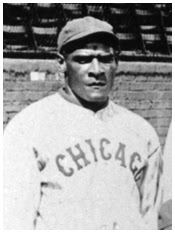

Blackball great and Hall of Famer Cristobal Torriente, arguably the greatest beisbol player Cuba has ever produced.

Regardless of exactly how President Obama’s recent relaxation of economic sanctions against Cuba and a possible movement toward normalizing relations between the island nation and the U.S. plays out, there’s no doubt that baseball historians — folks who frequently see modern political machinations as irrelevant to their line of work — are salivating at the potential for historical research into what is easily the Cuban national pastime as well.

Much of the baseball-and-Cuba-related conversations being bantered around now have focus on what could happen now, today. How will this affect the pipeline of Cuban baseball talent onto American shores and ultimately into MLB? How much will modern baseball in both countries benefit — or, perhaps, detract from — the quality of current play in both countries?

But what absolutely also needs to be considered is the doors that could be blown open on historical baseball research, and that could happen most profoundly in the field of African-American baseball history. There’s already a group of almost two dozen baseball researchers, many of them Negro Leagues specialists, that’s coalescing to take a boat trip to the island country for the purposes of historical documentation.

If Obama’s overtures toward Cuba possibly continue blossoming, that initial trickle of hardball researchers trekking to Cuba could become a flood. Imagine what we could learn about the rich but politically hidden heritage of baseball among the Cuban people if we could freely take a 30-45 minute plane ride from Miami to Havana?

It seems like many, many American sports fans don’t comprehend how HUGE baseball is in Cuba, how MASSIVELY it permeates Cuban culture at every level. It’s nothing like any of us now living have experienced in our lives in America. Even with the outsized popularity of the NFL in the U.S — and the NFL is the king of American sports right now — it still doesn’t come CLOSE to matching the Cuban obsession with baseball.

Martin Dihigo, another legend from Cuba

The next thing is that that obsession has been cultivated for well over a century, well before Fidel or Raul Castro were even born, let alone ruling the island with an iron Communist fist. Before the Marxist revolution on the island, American players — especially black ones — very frequently made the journey to Cuba to play in the winter leagues there, or even in the summer leagues, where Negro Leaguers were treated like heroes and often paid much better than they ever could have been in the Negro National and American Leagues.

For Negro Leaguers, Cuba — and, to be true, much of the rest of Latin America — represented not only a huge opportunity for financial enhancement, but also a chance, at least for a few months a year, at social respect and dignity on a scale that was unimaginable in the U.S. at the time.

As longtime Associated Press columnist Jim Litke told PBS Newshour a few days ago: “It used to be, quite frankly, sort of a wintering season for a lot of the great Negro League players, because Cuba allowed black players around 1900.”

(Of course, Cuba itself also has had and continues to have its own racially-based divides, with Cubans of African ancestry, i.e. descendants of sugar plantation slaves, often fighting for true equality with other, lighter skinned, Latino Cubans. Those are schisms that, to my understanding, were and are sometimes at best hidden and at worst encouraged by the Castro regime.)

So many legendary Negro Leaguers played in Cuban leagues at one point or another that the research possibilities that could be opening to us are, to many of us, mind-blowing, quite frankly. I’m not sure I’d want to go to myself — although if the opportunity for a free or heavily subsidized trip presented itself for me, I’d probably jump at it — but for many of my colleagues, it’s an opportunity that just cannot be passed up, and shouldn’t be. It’s something that for so long seemed unimaginable, something that was just never going to happen for a long, long time. And now it could, very soon.

Or maybe not. Obama has already faced considerable uproar over his moves, and that will only heighten in passion and influence.

And Jose Mendez

But as historians, a lot of us try to put petty modern politics aside when we do our job — we realize that the historical big picture is so much wider and more all-encompassing than whatever politically-motivated sniping occurs today. We realize that the continuity, unpredictability and ever-progressing motion of history is, in a way, what really matters. The passage of time never, ever stops, and, as a result, never does the tenuous state of current international sociopolitical affairs. History is about facts, but it’s also about nuance, neither of which, it so often seems, are qualities modern American politicians ever grasp.

While it can always be interpreted in many ways, fundamental history cannot change. It’s eternal, rock solid, etched in stone, so to speak. As a result, we need to learn about what has happened to help us not just figure out what will happen, but change and direct what will happen.

And baseball history, although admittedly just a small part of it all, adheres to those ancient truths and cultural progressions as much as any aspect of American and Cuban culture. It’s a beautiful thing, really, when you take a few steps back. A beautiful, beautiful thing. More from Litke:

“People in the U.S. don’t always know, as you mentioned in the introduction, the game goes back 100 years there. It was a rallying point when they fought a war of independence with Spain because the Cubans didn’t want to go to the bullfights. They wanted to play baseball.

“So it became a very, very important symbol in that society a long, long time ago.”