A few clips from the Louisiana Weekly in September 1934, when the Chicago American Giants, managed by Louisiana native and NOLA product “Gentleman” Dave Malarcher, came to the Big Easy to play the New Orleans Crescent Stars in a big showdown series.

Uncategorized

Bonner … James Bonner

Here’s a pretty intriguing post by Gary Ashwill that talks about Jimmy Bonner, a trailblazing African-American player in Japan that mentions an article I did for SF Weekly. But more importantly, it reveals the complex, interwoven tapestry of baseball among all people of color in the world. It is all indeed connected.

If you don’t already, make a habit of dropping by Gary’s blog, agatetype.typepad.com. Gary has been a huge help and source of support in my work, for which I am extremely grateful and his his debt.

Speaking of Panama …

1947: The Panamanian showdown

Pat Scantlebury

León Kellman

Many thanks to everyone who contributed names and thoughts to my post pondering whether there were any Negro Leaguers from Panama. I received several names of such players, including León Kellman, Frankie Austin and Pat Scantlebury, and a reader gave me this link to the Center for Negro League Baseball Research.

After doing some initial background reading about the players, I noticed that Kellman and Scantlebury are linked by more than just their native soil: Both of them played in the 1947 Negro World Series. Kellman put on the catcher’s padding for the NAL champion Cleveland Buckeyes, while Scantlebury took the mound for the NNL titlists, the New York Cubans.

The fact that both Kellman and Scantlebury were both top-notch players is indisputable; they both had long careers in the Negro Leagues, the Latin leagues, the minors and, in Scantlebury’s brief case, the majors.

For his part, Kellman received a good deal of credit for helping guide the scrappy Buckeyes to the NAL crown in ’47, an assertion made by, among others, the Cleveland Call and Post’s Jimmie N. Jones in January 1948.

Aug.10, 1948, Philadelphia Tribune with a photo of Kellman

The following season, Kellman had gained enough respect among his peers that he was selected to play in the East-West All-Star game at the tender age of 24. In reporting the selection, here’s what the New York Amsterdam News had to say about Kellman:

“Kellman is a team player, a quiet lad who goes about his baseball with a minimum of fuss and bother. He can play both third and second and has evenly divided his 1948 play at those two spots. According to the Howe News Bureau, Kellman is batting .329 with 70 hits in 213 at bat [sic] including 15 doubles, 2 homers and 27 runs batted in. Kellman has stolen 10 bases.”

As Kellman aged and matured, his tactical mind and popularity among his teammates made him an on-field leader and one of the emotional hearts of several squads, including the Memphis Red Sox, where he was under the tutelage of the great Goose Curry.

When reporting a rumor that Kellman was going to succeed Curry as the Sox’ manager for the 1953 season, wire service correspondent Sam Brown noted:

“Kellman has been with the Red Sox for the past four years, coming to the Red Sox from the now disbanded Cleveland Buckeyes. He is a sturdy fielder, fair hitter and a canny field judge. Kellman is credited with being the ‘brain trust’ behind the Curry regime. We have not learned just when he will report, but it is understood that he will be on hand in time for a few training sessions before the first game of the training season …”

Scantlebury, meanwhile, had an even higher-profile pitching career as a hurler. It was obviously big news when he played ever-so-briefly with the Cincinnati Reds in the summer of 1956.

But word about his prowess on the mound had leaked into the front offices of the major leagues as early as the late 1940s, peaking in the summer of 1948, when the Indians’ Bill Veeck inked him, along with Henry Miller and Fred Thomas, to tryouts with the Cleveland organization.

The media reports Scantlebury’s signing by the Indians

The three were reportedly scouted by Abe Saperstein, who informed Veeck about the trio. When reporting the news of the inking of the three, the Call and Post noted that although Scantlebury was already advancing in age — despite a few fibs on the pitcher’s part, Scantlebury was 30 at the time — he could still be a bankable big-league player, penned legendary scribe Doc Young in June 1948, just after the signing.

The Amsterdam News’ Joe Bostic was even more effusive when lauding Scantlebury — whom Bostic had covered often because of the pitcher’s place on the New York Cubans’ roster — after the Indians’ made their move:

“Scantlebury is one of those baseball rarities — a pitcher who is a feared batsman. Because of his proficiency and effectiveness with the willow, he has been the ‘workhouse’ of the Cuban club for the past three years. There was scarcely a game that didn’t contain the name of ‘Scantlebury’ in the box score either as a pitcher or pinch hitter. …

“Standing six feet one inch and weighing 187 pounds, Pat is a big man — and a strong one. Aside from his natural ability, ballplayers respect him as a great competitor. He is superb in the clutches. …”

But then Bostic penned a paragraph that wonderfully linked Scantlebury to his fellow Panamanian:

“Pitching against major league batters won’t be a new experience for [Scantlebury]. He toed the rubber against the Yankees during the ’45 training season and met the Dodgers in ’46. Although he has pitched against the likes of DiMaggio, Keller, Walker and Josh Gibson, he rates Leon Kellman of the Cleveland Buckeyes as the ‘toughest batter I ever faced.’”

Talk about ideal dovetailing for the purposes of this blog post. 🙂

Scantlebury unfortunately didn’t stick with the Tribe, but his praise of Kellman was no doubt inspired at least partly by his showdowns with Kellman during the previous year’s Negro World Series, in which Scantlebury, as a New York Cuban, hurled against the latter, a member of the Cleveland Buckeyes.

The 1947 World Series was hyped up by the media, even though it looked, to the unbiased observer, that the Cubans simply had the stronger team. In fact, Doc Young (who, as a Cleveland Call and Post writer, might have been a little biased) picked the Bucks to win the series in a Sept. 20 article:

“Taken on their league records, the Buckeyes should prove to be the more impressive of the teams. They own a sensational season’s average of .701 … They won the [NAL] pennant early in September with an 8 1/2-game lead. … On the other hand, the Cubans had to fight until last week to clinch the flag in their league with a record of 36-18. …”

Alas, though, the Cubans defied Doc’s prognostication and won the series and the blackball crown, four games to one. But, funny enough, the Call and Post excused its hometown team from the drubbing:

“Although the Buckeyes were far in front in the American League, they gave the impression that they weren’t too much interested in winning either the Series or the late-season ‘exhibitions’ with National League clubs.”

Uh-huh.

Nevertheless, the kismet of two natives of Panama playing against each other for the big crown was pretty sweet, I must say, especially given how the careers of both Kellman and Scantlebury had them each traveling hither and yon quite frequently. The fact that their trajectories crossed paths in the fall of 1947 was kind of remarkable, don’t you think?

Iron Claw unchained

As I’ve stated probably too many times before, I’ve become enraptured by the fascinating but rather arcane tale of NOLA’s Edgar “Iron Claw” Populus, a one-armed pitcher who for an ever-so-brief time in the early 1930s was the king of the hill in New Orleans blackball.

This post and this post try to fill in the background of Populus’ life, career, ancestry and heritage. I’m continuing to uncover so much quite cool stuff as I dig further into the Populus past.

What I’ve found is a family tree of biracial/mixed race — or “mulatto” or “Creole” in the parlance of the day — that stretches back into slavery in the mid-18th century before the early biracial Populuses (Populi?) were freed by their masters circa 1775 and began lives as quite successful free blacks.

In fact, at least two of Iron Claw’s direct ancestors fought for their country in the Army, including one slave-turned-trailblazing War of 1812 major. But those yarns are for ensuing posts.

Today, I’m going to talk about the Claw himself; specifically, his breakthrough pitching season of 1931, when he seemingly came out of nowhere to dominate opposing batters on the semipro diamonds of the Crescent City. But Edgar didn’t just mop the floor on the mound; he was also apparently quite a capable hitter who could crush ’em for extra bases on occasion.

The story — or at least the one the public knew — starts in late May of that season, when Populus took the hill for the Southern Stars. I’ll let the May 30, 1931, Louisiana Weekly take it from there:

“Thousands of fans stood spellbound Sunday afternoon while Edgar ‘Iron Claw’ Populus stood the Corpus Christi Giants up with two scattered hits and shut them out 8 to 0 … on the Corpus Christi grounds.

“The one-armed pitcher gave up three walks and contributing to his team’s battery movements by clouting a triple.”

Iron Claw whiffed seven in his coming-out party as well.

A week later, Iron Claw pretty much duplicated his breakout debut, but this time he did it on behalf of his previous week’s foe, Corpus Christi, which was apparently sufficiently wowed by what they saw to lure him away from the Stars. This time, Populus obliterated the Tiger Lilies 9-0 in the second game of a four-team doubleheader. Sayeth the Weekly:

“In calsomining the Tiger Lilies 9 to 0, Edgar ‘Iron Claw’ Populus hung up his second straight shut-out victory in a week. …

“Populus stood the Lillienes up with four scatetred [sic] hits while his mates accounted for a trio of bobbles.”

By now Iron Claw was being pulled every which way by a bunch of teams clamoring for his suddenly scorching-hot services. A week after leading Corpus Christi, he was back with the Southern Stars in a tilt against St. Raymond Giants.

The Louisiana Weekly, in previewing the feature contest, penned that “… Populus, the one-armed shut-out artist, will attempt to feed goose eggs to the hard hitting Saints. Populus will take the hill in behalf of the Southern Stars who will attempt to halt the win streak of the Giants while the Stars have a little chain of victories of their own they are nursing …”

What resulted in the clash was a draining, bang-up pitchers’ duel between Edgar and the Saints’ “Eagle” Lambert, a tooth-and-nail hurling battle to went into extra frames, ending in the 10th with a 3-2 St. Raymond triumph.

To quoteth the June 20, 1931, Weekly:

“Whew! What a duel ‘The Eagle’ Lambert and ‘Iron Claw’ Populus staged in St. Raymond Park Sunday afternoon.

“Both of them struck out a dozen men in ten innings and neither team secured more than eight hits. …

“Populus, who has turned out to be a real shut-out artist in these parts lately, started out as though he would attach another whitewash victim to his long chain when in the seventh inning he had not as yet allowed the Saints to chalk up a run against him, while his team held a 2 run lead.”

That’s when St. Raymond, who had previously made a habit of tallying runs in the seventh stanza, pushed two runners across the plate. But then both Populus and Lambert clamped down again, and the hurlers’ scuffle was back on, said the Weekly:

“During the remaining two and a half innings the spectators saw as brilliant a duel as could be asked for in anybody’s park. ‘The Eagle’ and the ‘Iron Claw’ settled down to the task of shutting out the opposition until their mates could get on to the other’s delivery.”

But in the end, it was the opposing thrower, Lambert, that cracked the game-winning, RBI double in the bottom of the 10th.

The loss left Iron Claw burning for a rematch against the Giants, and he got it a week later. And once again, it was nothing less than a spectacular pitching exhibition.

This time, it took 13 innings to decide the outcome of a duel between the Stars’ Populus and the Saints’ Harry Roth that had Louisiana Weekly sports editor Earl M. Wright calling the clash the best he had seen all season.

The game was a see-saw battle, and Iron Claw got into some serious trouble once or twice but managed to work his way out of it relatively unscathed. He also managed to produce an RBI double at the plate.

Unfortunately, the microfilm version of the June 27, 1931, Weekly darkens out Wright’s article on the contest to a large extent, making it difficult to discern exactly how the whole conflagration concluded. But from what I could tell, the Stars, despite the fact that Roth and Iron Claw were still in close-to-peak form, apparently successfully insisted that the game be called after 13 innings with a 2-2 deadlock.

But the result amongst the populace — pun possibly intended 🙂 — was the growing legend of the Iron Claw, who had proved himself capable of both pitching shut outs and lasting steadily through marathon, extra-inning contests.

By mid- to late-July 1931, none other than the mighty New Orleans Black Pelicans were seeking Populus out, and they successfully landed his services for what appeared to be the rest of the summer.

By that time the Black Pels had been reformed from the core of Welsh’s Travelers, a successful barnstorming aggregation that was headed by a familiar face (and spelled incorrectly): Winfield Welch. On a July Sunday evening, the Pels crossed bats with a foe familiar to the Iron Claw — St. Raymond — for an historic occasion: The first night game in NOLA between two “race” teams.

And the Welshies didn’t waste time — they locked up a 4-1 triumph in just one hour, 40 minutes. Iron Claw turned in his usual steady, crafty performance, reported the Weekly:

“‘Iron Claw’ Populus, on the hill for the Pels, gave up a half dozen bingles, but scattered them so well among the Saints that he was endangered but twice, in the sixth and seventh frames.”

Eagle Lambert proved the luckless loser, handcuffing the Pel batters to just three hits, but they were all doubles, and the defense behind him was, well, stinky. The game was also marked by the tossing of St. Raymond manager Herman Roth by the umpire after the skipper heatedly contested a controversial call. Roth got so honked off that he threw the elderly ump to the ground.

In the same week, Welch, the Black Pels’ manager, used Edgar Populus in relief during a game started disastrously by Iron Claw’s older brother, Adam, who gave up four runs in six innings. That doesn’t seem too bad, especially given that at the time Adam was yanked by Welch, the Pels were only down 4-3 to Corpus Christi. But, reported the Weekly:

“… ‘Lucky’ Welsh rushed ‘Iron Claw’ Populus, brother of Adam, to the hill and the one-armed boy stopped the (Big Hits’) rally as dead as a bag of door nails.”

Corpus Christi outhit the Pels, but Iron Claw scattered the hits he gave up well, and in the end the Pelicans’ George Collins walloped a game-winning round-tripper to hand his team, and Iron Claw in relief, the 5-4 victory.

The last time in 1931 that Edgar Populus appears prominently in the Louisiana Weekly was the Aug. 15 issue, which covered the Black Pels’ slugfest victory over the Melpomene White Sox, a local sandlot squad. Populus coughed up seven hits, but fortunately his mates banged out 20 of their own to pile up 22 runs in two innings in a 22-5 win. The Sox, who were basically an amateur team based out of the Melpomene neighborhood, were simply outclassed by “‘Lucky’ Welsh” and his mighty lineup.

From there, Iron Claw’s baseball career gets cloudy, and eventually his life deteriorated into a series of encounters with the law and other difficulties. But for one glorious summer, he was the ruler of NOLA blackball, a virtual Zulu King of the national pastime.

My next post or two will now take another look into the Populus family’s distinct, intriguing Creole past, particularly the war service of two of Iron Claw’s direct ancestors.

Otha Bailey: The imprecise nature of Negro Leagues research

As I noted in my previous post, I’m working on an article for Alabama Living magazine about lesser-known Negro Leagues players from that state. One of the figures on which I’m focusing is Otha Bailey, a catcher who had a roughly decade-long run in the Negro bigs from the late 1940s to the late 1950s.

From what I can gather, Bailey was often a back up to other, higher-profile backstops in the Negro Leagues, including to Pepper Bassett with the Birmingham Black Barons in early 1952. But he did begin to come into his own as he matured, including later in the ’52 campaign, when Negro Leagues kingpin, NAL president and newspaper columnist J.B. Martin gushed about him in a June 1952 article:

“There is one young man, however. who I think will soon be the best backstop in the league. The folks down in Birmingham, Ala., tell me that he already is the greatest in the loop.

“Whether you’re from Birmingham or some other city, I think you probably should be sure to watch this player in action. His playing is amazing for a young fellow. This backstop who is catching the fancy of the fans is Otha Bailey of the Birmingham Black Barons.

“According to the latest batting averages he rates in a three-way tie for seventh in batting in the NAL with an average of .333. Figures on his stick work, however, do not tell the real story of his value to his team.

“Bailey is outstanding for his fiery spirit and hustle. He has a strong throwing arm which cuts down a base runner trying to steal. …

“A native of Huntsville, Ala., [sic], Bailey is only 21 years old. Last year he caught for the New Orleans Eagles. Bailey is a squat 5 feet 7 inches and weighs 1t5 pounds. He hit .278 with the Eagles in 1951.

“Now, this player should some day be a great star. I like players with fire and hustle. They can inspire their teammates to great things. …

“If he keeps up his early form, I am sure Bailey will be one of the stars you see on the field if you come to Comiskey Park in Chicago, Sunday, Aug. 17, for the East-West game.”

Martin’s prophecy did indeed come true — Bailey suited up as the starting catcher for the East team that August, and he ended up have a mixed day. He cracked a doubled at the bat and drove in a run, but he also allowed two passed balls behind the plate in the East’s 7-3 defeat in front of 18,000-plus fans.

Unfortunately, Bailey passed away on Sept. 17, 2013, in Birmingham. Hundreds of mourners reportedly jammed Rising Star Baptist Church in the city to, as reporter Bryant Somerville of ABC 33/40 wrote four days later, “say a final goodbye to one of the original Negro League baseball players.”

But here’s the catch — and that’s not an intentional play on words on Bailey’s nickname, “Little Catch,” which he earned from teammate because of his small but scrappy nature. It’s been impossible to pin down Bailey’s precise birthdate; a host of different sources list wildly differing dates.

The obituary his family provided to the Birmingham News/al.com states it as June 30, 1930, a figure backed up by Baseball-Reference.com. But the U.S. Public Records Index pegs it at June 6, 1933, and the Social Security office lists it as June 29, 1928! Then, finally, the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum’s online bio of him gives a date of … June 30, 1920!

Unfortunately, I couldn’t immediately find a direct birth record online as of now, so the mystery will have to remain. But what isn’t a mystery is that Little Catch loved the sport, and it loved him back. Pretty cool.

“That was his passion”

I’m working on a story about lesser-known Negro Leagues stars from Alabama for Alabama Living magazine in recognition of the new museum being built in Birmingham. (I’ll comment soon on whether this new facility will take away from the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City.)

While working on the article, I’m shining a little spotlight on Clifford DuBose, who played for the Memphis Red Sox and Birmingham Black Barons in the late 1950s, just before the final demise of the Negro American League. DuBose was from Montevallo, Ala., current population just under 5,000.

I just discovered that, unfortunately, Mr. DuBose recently passed, but I was able to speak with his brother, Glover, for a few minutes this past weekend. Glover was extremely effusive in praising his brother’s brief Negro Leagues career and his love of America’s pastime. Glover noted that Clifford was especially proud of his long post-professional tenure as a sandlot and Little League coach and volunteer.

“That was such a big thing going for him,” Glover said of Clifford’s time in the Negro bigs and beyond. “He was always a baseball man. That was his passion, baseball.”

That pretty much sums up in a nutshell how so many Negro Leaguers felt about the game. Wonderful. 🙂

Brit and Iron Claw … some thoughts and revelations

I hope to go into detail more about both of these soon, but here are a few interesting things I’ve discovered about a couple blackball pitchers who have captured my attention …

First up is Alex Albritton, to whom Gary Ashwill alerted me as part of my research into the 1948 death of Cannonball Dick Redding at a Long Island psychiatric hospital. While I initially had questions into how Redding died under reportedly “mysterious circumstances” — subsequent investigation and patience on Gary’s part revealed a death certificate that claims syphilis was the cause of death (not sure I’m buying that) — at Pilgrim State Hospital in Islip, N.Y., Gary suggested I look into the tragic death of Albritton — who pitched for Hilldale, the Philadelphia Giants and other minor teams, mainly in the 1920s — at Byberry State Hospital in Philadelphia in 1940.

Unlike the vagaries surrounding Redding’s end, the death of Albritton has never been in any doubt — he was beaten to death by an attendant whom Albritton had smacked over the head with a broomstick. I’m currently working on a story about the incident for philly.com for a sort of macabre, creepy and tragic story for Halloween.

While Albritton’s death was big news in Philly and in the black national press — how he died was never in doubt — the attendant, Frank Wienand, who was initially arrested and charged with homicide by the local coroner, was eventually cleared and absolved of all blame in the matter, thanks to a ruling that said he more or less acted in self-defense in a corrupted, underfunded hospital system for which he shouldn’t be blamed.

The insane asylum that was Byberry

During a cursory glance through history, I’ve found a few noteworthy points about “Brit.” One, the death certificate Gary, and now I have doesn’t include an official cause of death — it’s just stamped with “INQUEST PENDING.” That in itself is eerie.

Two, if we thought Pilgrim hospital was bad … apparently Byberry had an even more horrific history of abuse, torture and death. Over a matter of just a few decades in the mid-20th century, possibly over 100 violent, mysterious, sudden or otherwise unexplained deaths at the hospital. Its conditions were attributed by some government officials to poor institutional oversight and a woeful lack of funding that resulted in an insufficient amount of staff that was already underpaid.

Finally, and this could be the oddest item I’ve uncovered … according to both Seamheads.com and his death certificate, Brit was reportedly buried in Eden Memorial Cemetery in Collingdale, Penn. Eden is one of the most historic African-American cemeteries in the country, with numerous black luminaries interred there, including baseball figures Octavius V. Catto and Stanislaus Kostka Govern.

From the Eden Cemetery Web site

However, I wanted to confirm that Albritton is, in fact, buried there, and I also wanted to track down a suspicion that he, like so many Negro Leaguers, was laid to rest in an unmarked grave. But after calling the cemetery offices, a staffer there found … absolutely no record at all of an Alex Albritton interred there in 1939, 1940 or 1941. Is something fishy …?

For Albritton, you’ll have to wait until my story comes out. 🙂

OK, the other pre-integration pitcher I was to touch on is one-armed New Orleans wonder Edgar “Iron Claw” Populus, about whom I’ve written recently. Although Iron Claw was mainly a local NOLA semipro and sandlotter, his story has fascinated me, not only because of his disability, but because he flashed like a comet across the N’Awlins blackball heavens in a magical 1931 season, then seems to have largely disappeared from the local hardball scene. (I’ll chronicle that season in an upcoming post, hopefully this weekend, but I’ll see.)

But as I dug into Populus’ familial heritage, I found something perhaps even more fascinating than Iron Claw himself — his ancestry. This is something I’ll also try to go into more depth soon, but I discovered that Edgar Populus’ family tree stretches back into New Orleans history for numerous generations. While a lot of it is still muddled and unclear at this point, the Populus line, and many of its offshoots, are biracial — or, in other terms of the day, Creole or mulatto — in nature, the obvious mixing of wealthy white owners, who were probably largely French, and their slaves.

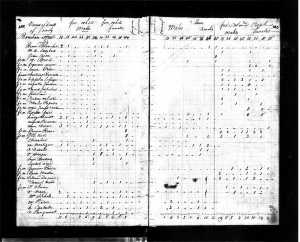

1810 federal Census report featuring one of Iron Claw Populus’ direct descendants

Edgar Populus’ line in New Orleans can be traced back at least to his great great great grandfather, Vincent Populus, who lived from 1759 to 1839. While I have yet to uncover proof that Vincent or anyone in his direct line of descent to Edgar owned slaves, it appears that many of Vincent’s early relatives were, in fact, biracial men who owned slaves themselves.

All those factors immerse local pitching great Iron Claw Populus’ ancestry firmly in the murky, complex and sometimes downright confusing racial, social and class history of perhaps the most culturally and ethnically diverse cities in the country. While I do have a cursory knowledge of that interwoven sociology, much of it is and will be new territory for me to explore down the road, and I’ll chronicle it the whole way …

Congrats to one of my biggest fans

I know this isn’t directly about the Negro Leagues, but I wanted to congratulate and say thanks to one of the biggest, most loyal supporters of my work into the Negro Leagues, David Hammer.

Tonight, David will become the first inductee into the Ben Franklin High School football hall of fame in NOLA at the school’s homecoming game. David is a couple of years younger than me, and he was a much better athlete than I ever was. He started at quarterback for Franklin — which is perhaps the best public high school in New Orleans — for several years and even once played against a team led by none other than Peyton Manning.

David won multiple city student-athlete awards as a Franklin Falcon, and he went to Harvard for college, as did his father (his mother went to Duke). From what I recall, he played freshman football for the Crimson, but eventually decided to focus on his studies and student media. That’s also where he met his lovely wife, Lucia Paredes. They now have a cool little kid named Teo, who’s a HUGE Beatles fan and can also play “Smoke on the Water” on guitar.

David himself, meanwhile, has moved up the investigative-reporting ladder and is now an award-winner investigator at WWL TV here in his hometown. To say that I’m extremely proud of him is a massive understatement. But I did teach him everything he knows. 🙂

But as soon as we met way back in 1997 in good ol’ Holyoke, Mass., in the summer of 1997, we became fast, close friends and have remained so for, wow, 17 years. Can’t believe it’s been that old, and how old both of us are. We bonded over Public Enemy, and it only grew from there.

David has also always been a huge supporter of me, my work and my life, and he’s consistently been there for me during all of my personal and professional struggles. There’s no doubt in my mind that I wouldn’t have made it this far without him and his support and love.

One of the biggest areas in which David has supported me has been my passion for, research into and writing about the Negro Leagues. he has encouraged me and cheered me on from the beginning, and his support over the years has been invaluable to my spirit and my heart. He and Lucia bought me a hardbound copy of “Only the Ball Was White,” a Negro Leagues Legends poster, and a Negro Leagues game.

So many, many heartfelt and grateful thanks to David (and Lucia and Teo) for all they have done for me in my quest, and hearty congrats to my pal on his honor tonight. I love you, man.

Birmingham’s Lyman Bostock Sr.

Lyman Bostock Sr.

To shift gears a wee bit away from Cannonball Redding, I’m working on an article for Alabama Living magazine about the new Negro Leagues museum being built and opened in Birmingham, and the story will feature some of the lesser known — at least lesser known to the general public and readers of the magazine — Negro Leaguers from the state.

Many people in Alabama know, for example, that Satchel Paige was from Mobile, and that Willie Mays began his pro career with the Birmingham Black Barons, but many readers of the magazine might never have heard of ‘Bama natives Dizzy Dismukes, Ted Radcliffe or Otha Bailey.

Or the man I’m going to spotlight in this post, Lyman Bostock Sr., who was born in Birmingham in 1918 and enjoyed a generally successful career from the late 1930s into the early ’50s. (Note that throughout the tale Bostock’s career crosses paths with that of Winfield Welch, a Louisiana native whom I’ve highlighted frequently on this blog.)

Many baseball fans have heard the name Lyman Bostock, but usually it’s Lyman Jr., who was a budding Major League star in the 1970s until he was murdered in 1978 in a case of mistaken identity.

But the younger Bostock inherited his love of and aptitude for baseball from his father, a star in the Negro Leagues in the 1940s …

Lyman Wesley Bostock Sr., according to Social Security records, was born on March 11, 1918, to parents John and Lilly (Greenwood) Bostock. John was an Alabama native, né 1886 in Daleville, but Lilly was born in 1890 in Georgia. Lilly died in 1980, far outliving her husband, who passed away in 1941 in Birmingham.

Little Lyman appears to have spent his earliest years living with his mother and her parents, Robert and Annie Greenwood, in Birmingham. But by the 1930 U.S. Census Lyman had joined his father, mother and siblings on 15th Street in Birmingham. John was a public school teacher, while Lilly was a housekeeper with a private family.

When it was time for the 1940 Census, the 22-year-old Lyman was an iron pipe worker along with his father and still living on 15th Street in Birmingham. By 1941, though, Lyman’s Negro Leagues career was already blooming. A first baseman for the Black Barons under skipper Winfield Welch, Bostock was voted into the prestigious East-West All-Star game in Chicago in 1941.

Bostock also took park in a special North-South doubleheader in August 1941, when the Barons took on the New York Black Yankees at Yankee Stadium. The Aug. 9, 1941, issue of the Norfolk New Journal and Guide featured a large photo of Bostock with the tagline “Star Player” over it. The cutline below the photo called Bostock “one of the top notch veterans the Southern team will throw in against” the Black Yanks. Bostock ended up scoring a run in the Barons’ 2-1 win that day.

Bostock’s hardball career was interrupted in April 1942, when he enlisted in the Army to join cause in World War II; he was one of almost a dozen Black Barons who answered the call to serve.

By 1946, with the war won and military veterans coming home, Bostock restarted his baseball tenure, but a salary dispute with the Black Barons’ owner, Tom Hayes, Bostock was tempted to bolt from the Birmingham squad, which had already lost Welch, who had resigned as manager of the squad.

But Bostock apparently ultimately remained in the Birmingham fold, and in July 1946, in a doubleheader against Welch’s barnstorming Cincinnati Crescents team, Bostock bashed a home run, added a single and scored to runs in the Barons’ 4-2 victory, which completed the two-game sweep of the Cincinnatis.

Bostock did end up leaving the Black Barons later on, but after a stint with the Chicago American Giants, he seems to have returned to his hometown — he joined up with another former Barons manager, Tommy Sampson, on the latter’s Birmingham-based Sampson All-Stars in 1948.

Bostock enjoyed another career highlight in October 1948 when he was asked to join Jackie Robinson’s barnstorming all-star team as a capable outfielder.

The following season, though, Bostock was back with the American Giants, who were now skippered by none other than Winfield Welch (who by that point in his career had picked up the nickname Gus). Welch shifted Bostock from the outfield back to the latter’s natural position, first base.

In 1949, still as a Giant, Bostok was among the leaders in hits in Negro American League. In July of that year, Hall of Fame sportswriter Wendell Smith reported that Bostock might be signed by the San Diego Pacific Coast League to replace the injured Luke Easter at first, but that didn’t come to pass, and Bostock remained one of the best first sackers in black baseball. In its Aug. 9, 1949, issue, the Atlanta Daily World published a large photo of Bostock, calling him the “hard-hitting Chicago American Giants’ first base man … Bostock is hitting .346 and critics consider him the best first sacker in the Negro American League. He is a big man with plenty of power. Weight 200 lbs, 6’1″ tall and will hit the best of pitchers.”

The 1949 campaign ended on a low note for Bostock, though: He became the last out in the NAL championship series between the American Giants and the Baltimore Elite Giants, who completed a four-game sweep over the hapless Windy City squad.

Bostock then floated around blackball until retiring in 1954. He remained close to the game, however; in spring 1956 he joined Goose Curry as the heads of a Black Barons tryout school for prospective signees, for example.

Bostock remained in his hometown until his death on June 23, 2005, at the ripe old age of 87. Unfortunately, he had tragically outlived his son.