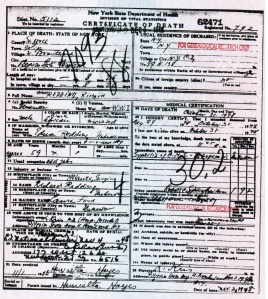

In the days following this post I put up, a lively discussion popped up on the Malloy conference Facebook page about whether the fact that the great fireballer Cannonball Dick Redding, according to an unredacted death certificate, died from syphilis at Pilgrim State mental hospital in Islip, N.Y., on Long Island in 1948.

While Pilgrim was indeed notorious for poor living conditions, questionable medical practices, and shoddy and at times violent treatment of patients at the facility, Redding’s death certificate appears, at least on the surface, rule out any foul play in his heretofore unknown cause of death.

But Professor James Brunson at Northern Illinois University made some very valid points and somewhat sharp criticism on the fact that my blog indicated that Redding died from the long-term psychological effects of a sexually-transmitted disease. Professor Brunson, an expert in the representation of African-American ballplayers in the mainstream media, believes that by revealing syphilis as the cause of death only reinforces the negative stereotype of the hypersexual —and, therefore, dangerous — black male in America. It was this image and representation, for example, that was, some argue, the real reason for the century-long existence of Jim Crow segregation in the South, i.e. the desire to keep “colored brutes” away from fair white maidens.

Hence, Professor Brunson feels that simply saying Redding died of “natural causes” at a mental hospital is sufficient, that there is no need to further reinforce negative stereotypes of African-American males.

However, I argued — and Dr. Ray Doswell at the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum very gently supported this argument — that the cause of death, regardless of what it is and how politically correct it might or might not be, is relevant to the chronicling and piecing together of the final years, months and days in the life of a legendary Negro Leagues pitcher who some put on a par with Satchel Paige and Joe Williams. Facts are facts, and all of them, ugly or not, must be known to provide a complete picture of any person’s life and unfortunately premature death.

(In addition, just saying “natural causes” prompts readers, historians, etc., to naturally wonder, “OK, well, what does that mean? What type of natural causes?”)

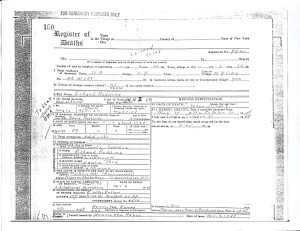

I also referred to my tendency — call it the Fox Mulder effect — to suspect conspiracies and resulting cover-ups of said conspiracies. I put forward the theory that the doctors and staff at Pilgrim knew that the stereotype of a hypersexualized black male not only existed, but was prevalent and feared, and those doctors possibly used that negative image to cover up what could have been the true cause of Redding’s death — foul play, mistreatment or lack of treatment. There are enough discrepancies — many of them very subtle — between the two death documents that cause me to suspect the Cigarette Smoking Man (or at least the powerful powers-that-be that he represents in general) had a role in all this.

Further, I lamented the fact that Redding’s syphilis went undiagnosed and, therefore, untreated for so long that it caused his premature death. That speaks to a tragic gap in medical care between the haves and the have-nots, who, both in the 1940s and still running into today, are often African Americans. Perhaps the real racism in this story is not the reinforcement of a stereotype but the idea that Dick Redding died because he was poor and black and didn’t have access to the type of health care that could have saved his life in the first place.

Also factoring in here, I believe, is the stigma that historically — and, sadly, contemporarily — was and is still attached to mental illness. While treatment and views of mental illness have certainly improved since Redding died in 1948, nearly seven decades ago they were primitive and all too often tragic. How much, we must ask, has this really changed by 2014?

I subsequently sought the input from Gary Ashwill, who received the unredacted copy of Cannonball’s death certificate in the first place. I asked him if he was buying this official “syphilis” line. Gary answered that, with the lack of any hard or even circumstantial evidence to the contrary, he’s inclined to accept the death certificate at face value.

But Pilgrim State Hospital had a very macabre history when it came to the treatment and fate of patients, with mysterious deaths — and occasionally brutal — deaths taking place.

(That fact, by the way, will hopefully lead to a new post about a player to whom Gary tipped me off — Alex Albritton, a pitcher for the Hilldales and other squads who was, in fact, beaten to death in a Philadelphia asylum in 1940. More soon.)

So, what are your thoughts on all this?