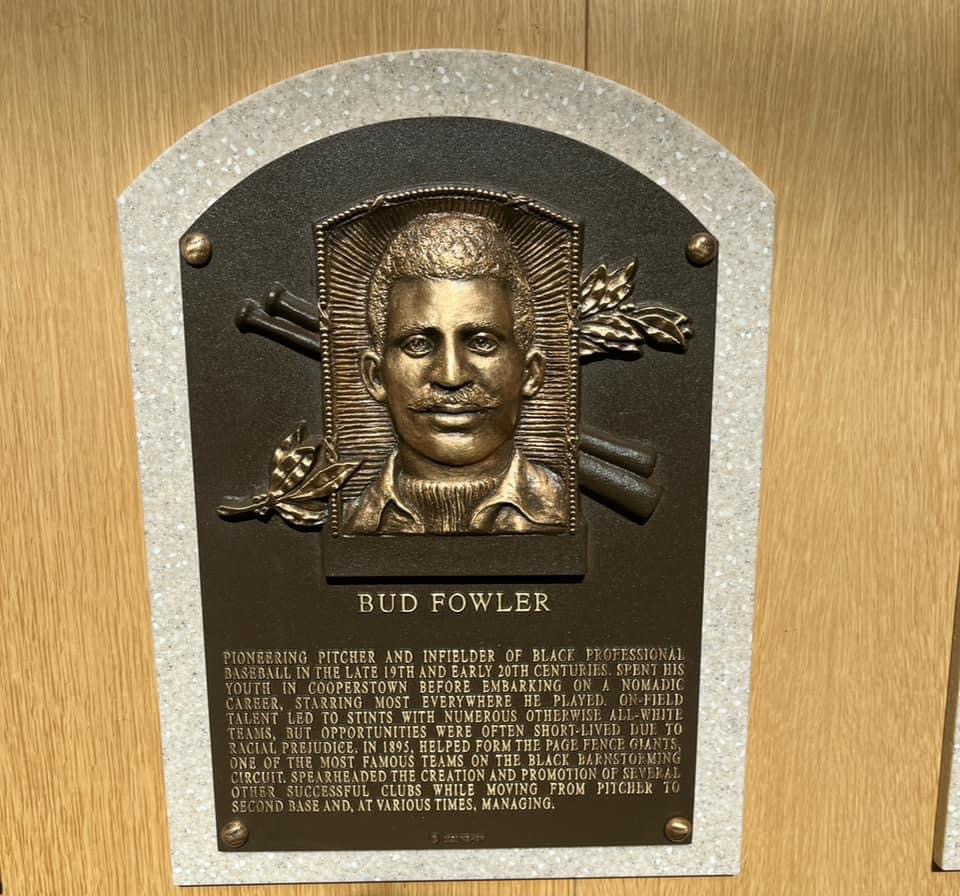

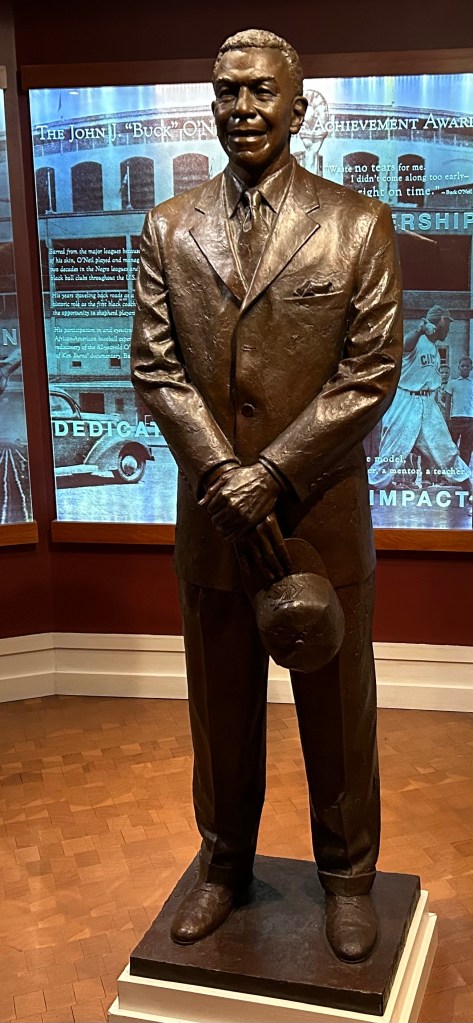

When you’re visiting the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, N.Y., there’s something quite stirring about entering the Plaque Gallery and seeing all the bas relief, rectangular, wooden plates hanging on the walls, each one displaying the image and short biography of one of the figures who have been enshrined in the Hall.

There’s a solemnity and an aura of greatness that permeate the Plaque Gallery and place visiting the massive room near the top of many a baseball fan’s bucket list of things to do before they die.

It was against this backdrop that dozens of Negro Leagues researchers, scholars and fans gathered on the evening of June 6 for a meet-and-greet reception for another edition of SABR’s annual Jerry Malloy Negro Leagues Conference.

The Malloy conference had never been held in the hallowed halls of Cooperstown, but apparently the Hall of Fame had been the ones to reach out to us about holding the Negro Leagues conference in Cooperstown.

And I, for one, felt incredibly honored to be welcomed by such an illustrious institution as the NBHOF, and I’m sure many of my friends and peers felt the same way. However, the feeling might have been mutual, or at least that’s what NBHOF President Josh Rawitch told us in his opening remarks.

“It’s an incredible honor to have this group here,” Rawitch told us. “You could have gone anyplace, and you came here. To pick us is an extraordinary, true honor for us. …

“This place is unbelievable,” he added about the Hall of Fame. “It’s truly one of the most spectacular places on the planet.”

Long-time Malloy attendee (and my perennial conference roommate) Ted Knorr also gave a few thoughts, which included, quite significantly, a call to elect more segregation-era Black baseball figures to the Hall. He noted this while the Hall of Fame continues to tinker with the election in a way technically allows more Negro Leagues to get in while at the same time essentially being no change at all, for all practical purposes.

In light of this, perhaps one question to ask is why the Hall had been so eager to host the Malloy gathering. More specifically, I found myself pondering whether the HOF’s overture to the SABR Negro Leagues Committee might have been essentially a public relations move by an institution that continues to receive criticism from Black ball advocates for consistently failing to adequately honor Negro Leagues greats with induction.

The fact is that the Hall persists in snubbing many Negro Leaguers who more than deserve induction, despite middling changes to the voting rules and token gestures of respect for those African-American legends, showing a still stunning level of disrespect for and ignorance of Negro Leagues history. So maybe hosting the Jerry Malloy conference was an effort by the Hall to blunt or mute such criticism and make itself look just a little better, or at least less awful.

(I want to note that the opinions and interpretations of the preceding two paragraphs are my own personal beliefs and thoughts and do not necessarily represent anyone else within the Negro Leagues community or the Malloy committee itself.)

Having said all that, I wanted to highlight a few themes that ran through the three-day conference.

The first, quite naturally, was the emphasis on the life, career and legacy of Bud Fowler, the 19th-century African-American star player, manager, owner and executive whose ambition, courage, resilience and persistence laid the spiritual groundwork for all of the Black baseball teams, leagues and business ventures that came after him. For details about Fowler’s life and impact, check out this, this and this. Also, here’s info on the fantastic biography of Fowler by the late Jeffrey Laing.

Bud was not only recently inducted into the HOF (along with Buck O’Neil) in 2022, but he was also a native of Cooperstown and had deep roots and connections to the central New York State region.

To start, Bud is on the cover of the 2024 Malloy Conference’s souvenir program, and on the Sunday after the conclusion of the official conference proceedings, a carpool was planned to visit Fowler’s grave in nearby Frankfort, N.Y.

But the best homage to Fowler at the conference was on Friday afternoon with the hour-long panel on Bud, moderated by the stupendous Alex Painter, who dubbed the panel “the Fowler Hour.” Unfortunately, one of the panelists, 19th-century Black baseball author and expert James Brunson, was unable to participate, leaving Alex and educator/historian Brian Sheehy as the dynamic Bud Fowler duo.

Sheehy, who had extensively researched Bud’s time in Massachusetts, where he played as a ringer of sorts for multiple integrated teams at the beginning of his long career in pro baseball, gave a presentation about this time in Fowler’s career. Sheehy addressed the several lingering question marks and mysteries about Bud’s escapades in the Bay State.

“He was actually a nomad,” Sheehy said of Fowler. “It’s important for us to remember that, and it’s important for us to fill in that story.”

Following Sheehy’s talk, Painter unspooled the tale of the Indianapolis Colored Baseball League of 1902, one of Bud’s final efforts to jumpstart an organized African-American baseball circuit – and, Painter said, one of Fowler’s most little-known ventures.

“He understood what the benefits of an organized Black baseball league could mean,” Painter said.

While the ill-fated ICBL didn’t last very long at all – it didn’t come close to completing a season – it did spawn the soon-to-be-legendary Indianapolis ABCs, one of the greatest Black teams in history. The league also, unfortunately, might have triggered Bud’s physical decline when one of Bud’s baserunning slides led to a broken rib that apparently pierced his kidney. The injury seems to have triggered deteriorating health that led to his death in 1913, just short of his 55th birthday.

Alex noted that during Bud’s last years, “[H]e was keenly aware of his place in baseball history.”

The second topic that particularly piqued my interest was less of an actual theme but more of a dandy doubleheader that hit close to home for me – baseball trading cards.

Like many of the men and women who always attend the Malloy Conference, I collected baseball cards as a kid. A lot of them. And one of the biggest regrets of my life is eventually selling most of them off several years ago. It’s a pain that never goes away.

But a pair of presenters on Saturday afternoon during the conference buoyed my spirits a bit by discussing a few landmark card sets that helped bring the Negro Leagues into the lives of baseball fans who otherwise hadn’t known much about pre-integration Black baseball.

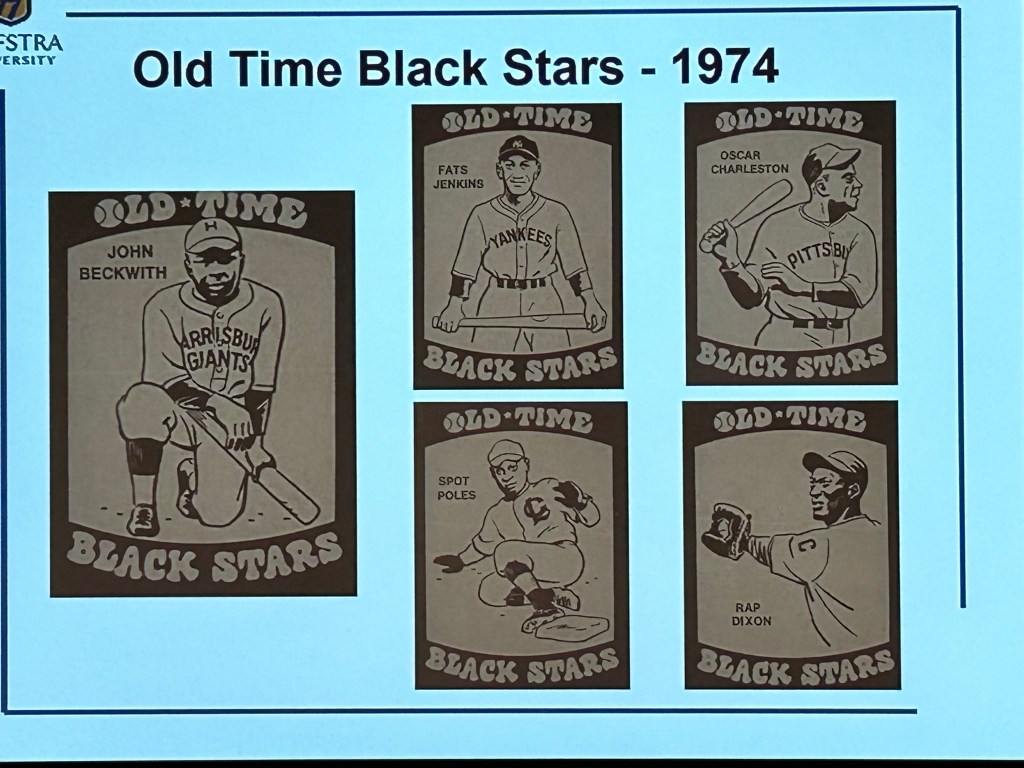

The first speaker was Rich Puerzer, a perennial Malloy attendee and presenter, who this year regaled the audience with the story of the Laughlin Negro League Baseball Card Sets. The Laughlin line of Negro Leagues trading cards were the creation of Robert “Bob” Laughlin, a cartoonist and card-making entrepreneur who came out with his first line of Negro Leagues cards in 1974, a set dubbed “The Old-Time Black Stars” and totaling 36 cards. That was followed by a 12-card set honoring the famous Indianapolis Clowns team in 1976, then a third line in 1978 called “The Long Ago Black Stars,” boasting 36 cards.

Puerzer discussed Laughlin’s motivations and goals for creating the three lines; how he went about compiling, designing and printing them; and the cards’ importance to the documentation and teaching of Black baseball history.

Puerzer said that while the Laughlin sets weren’t as popular as the Topps company’s annual MLB sets, Laughlin – who was a bit of an outsider in the sports card world, Rich said – was nonetheless “truly ahead of this time.”

Puerzer said that for many collectors, the ’74 Laughlin line – which he noted possessed “a simple elegance“ – was “something of a passport to the Negro Leagues.” He added that the 1976 and ’78 sets were just as beautiful and impactful as the landmark 1974 set.

“Several of them are really beautiful cards,” he said. They bring the humanity of the players to the fore with a simple and beautiful style.

With the Laughlin sets, Puerzer said, the Black baseball figures “finally received their due. Many of them were on a baseball card for the first time.”

Puerzer was followed by Steven Greenes, who gave a presentation titled, “Negro League Baseball Cards and Memorabilia as a Roadmap to History,” which filled in all the trading cards and other ephemera of Negro Leaguers leading up to the groundbreaking Laughlin sets.

Greenes noted how cards of Black players existed back to the mid-19th century, with a lot of them made in Cuba, Mexico and the Dominican Republic that depicted African-American players who competed in the integrated leagues or teams in those countries.

Other important cards or products of Black players included copies of ta team photo of the famed Page Fence Giants team in the 1890s; a card of pitcher Jimmy Claxton in a 1916 line of cards of Pacific Coast League players by the Zee-Nuts candy company; and an extremely rare 1951 card depicting Josh Gibson’s days playing in Puerto Rico.

Post-integration, the first mainstream United States company to issue a card of a Black player was Leaf’s 1949 Satchel Paige card, which Greenes called “the rarest and most significant post-war baseball card.” He added that authentic cards of Gibson from various lines are the most sought-after Negro Leagues cards.

However, he added, “just about every Negro Leaguer had one or two cards of them made.” He said that “the value of such cards mirrors the public’s love and knowledge of the Negro Leagues,” and noted that amidst the boom in sports card collecting during and after the Covid-19 shutdowns, “no other cards have increased in value more,” with some increasing by 10 times the value.

“People are really recognizing these players as the greats they were,” Greenes said.

(As a side note, I was one who used the pandemic shutdowns to start collecting sports cards again, including baseball ones. I fully admit that my renewed passion stems in large part from a desire to relive my childhood and regain some of the magic that collecting brought me in my youth. And it goes without saying that Cooperstown’s downtown is jammed with card memorabilia shops. Seriously, it’s like every third storefront. It’s glorious.)

The third theme that permeated the 2024 Malloy Conference was the presence of several relatives or descendants of important figures in Black baseball history, starting with Max Martinez Almenas, a descendant in the great Martinez baseball family.

Almenas related how the four Martinez brothers – Antonio “Tonito” Martinez, Horacio “Rabbit” Martinez, Aquiles Martinez and Julio “Julito” Martinez – helped pioneer baseball in the Dominican Republic and left their indelible mark on the significant but overlooked importance of Dominicans in the Negro Leagues and baseball throughout the Americas as a whole.

Max, the grandson of Tonito and the grand nephew of the other three brothers, is directing a documentary by the Martinez Beisbol Films production company titled, “The Martinez Brothers: The Untold Story of Talent, Tragedy, and Legacy.” Here’s a description of the documentary in the Malloy Conference program:

“Our narrative delves into the personal and professional hurdles they overcame, showcasing their journey through a visual feast that captures the essence of triumph and sorrow. The documentary promises a compelling voyage into the heart of the Martinez legacy, highlighting their contributions, struggles, and the profound impact they left on the sport. It is a story of resilience, family bonds, and an enduring legacy that inspires generations.”

Said Max during his presentation: “There are many people that know the history, but many more need to be taught the history.”

He added that the Martinez brothers were among “the first wave of Dominicans in baseball [in the U.S],” and that “they established the original pipeline of professionals from the Dominican Republic to Major League Baseball.”

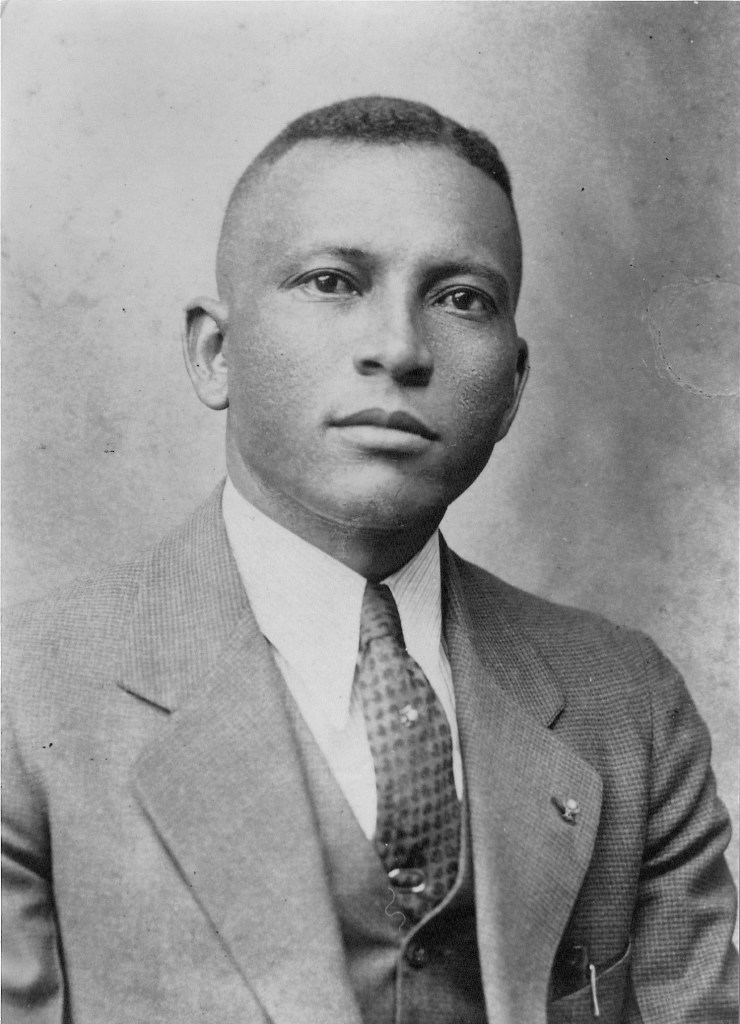

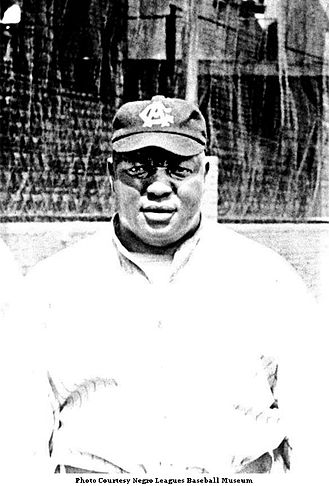

Right after Max’s presentation came one by J.B. Martin IV, the great grandson of Dr. J.B. Martin Sr., a Memphis dentist who, along with his brother (and fellow dentist) B.B. Martin, founded and operated the Memphis Red Sox from 1920 to 1959.

The Red Sox shifted from league to league and from level to level, including stints in the Negro Southern League, the first Negro National League and the Negro American League. J.B. Martin built Martin Stadium for the Red Sox, who were one of the few Black baseball teams to own their own stadium.

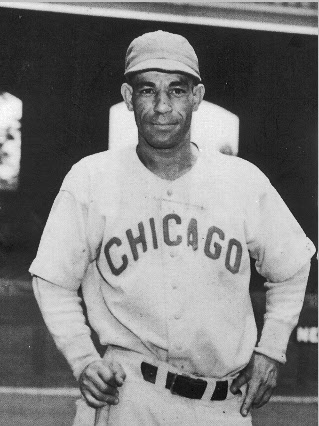

Into the 1930s and ’40s, Martin spent a lot of time in Chicago, where he eventually became co-owner of the famed Chicago American Giants, who were past their prime but still played in the Negro League “majors.” J.B. Sr. and served as president, at various times, of the Negro Southern League, the Negro American League and the Negro Dixie League.

At the Malloy conference last month, J.B. Martin IV regaled attendees with tales of his great grandfather and the Red Sox. Martin IV said he works to educate the public about his great grandfather, as well as campaign for the senior Martin’s possible election to the Baseball Hall of Fame.

“His accomplishments were important to the Negro Leagues, and his achievements deserve recognition,” the younger Martin said.

Because the Memphis Red Sox were a family-operated affair, and because they owned their own ballpark, Martin IV said the team enjoyed “a unique situation in Memphis, and they drew a lot of the best players.”

Martin Sr. was also a prominent figure in the local Republican Party, and his progressive activism earned the ire of the Memphis Democratic machine that governed the city with an iron grip and threatened the Martins’ safety and extensive, successful business interests.

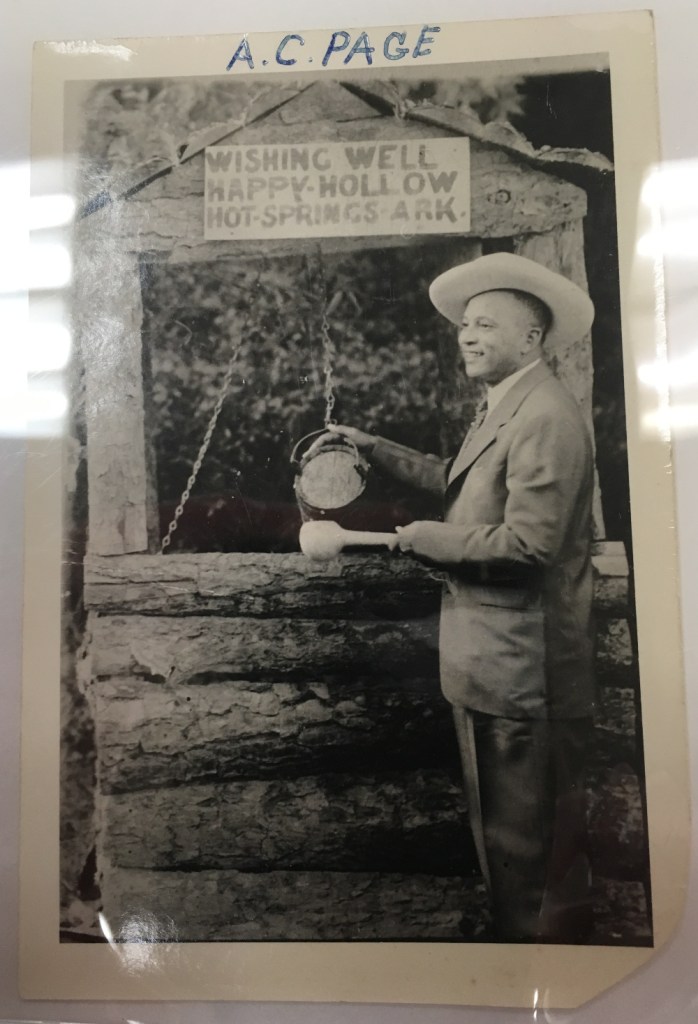

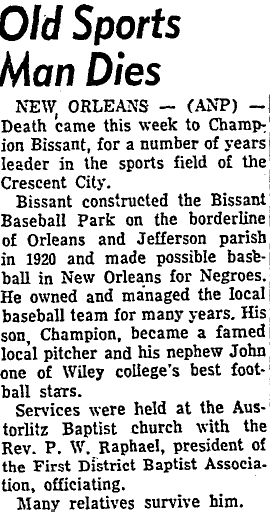

I’ll cap off the bulk of this post with thoughts by another descendant of a legendary figure in segregation-era Black baseball in the South, Rodney Page, who also attended the conference and whose father, Allen Page, was arguably the greatest and most influential person in the Black ball scene here in New Orleans for three decades.

Allen Page founded, bought and owned several pro and semipro clubs in the Big Easy, and he frequently played a role in the national Black baseball competition and management. Rodney said at the conference that his father knew J.B. Martin well; the seniors Page and Martin were both among the most prominent Negro Leagues operatives, promoters and executives in the South. Rodney noted that his father was friends with Martin, who often visited the Pages in New Orleans.

“I know a little bit about J.B.,” Rodney said drolly.

Rodney commented at the conference that there are not enough businessmen in the Baseball Hall, even though it was the money men and women who often took the type of chances that could make or break a team or a league. He said that African-American entrepreneurs in the Jim Crow South, including those in the baseball business, took great financial and personal risk to create a lasting, thriving economic entity.

“I know that first-hand,” Rodney said.

He added that Martin absolutely belongs in Cooperstown.

“To me, and I’m biased, this should be a slam dunk,” Rodney said of Martin’s HOF prospects. “From my perspective,” he added, addressing J.B. Martin IV, “it was the owner and executive and promoter who moved the Negro Leagues from the sandlots to significance. Your great grandfather was one of those.”

I capped off my visit to Cooperstown on the morning of June 9, when I sat down for a short interview with Rodney Page. Several conference-goers – including me and my roommates Ted Knorr, Lou Hunsinger and Bruce Emswiler, as well as Rodney and friend and fellow perennial Malloy attendee Al Davis – stayed at the Lake View Motel, located along Otsego Lake a few miles north of Cooperstown proper.

On Sunday, I quizzed Rodney about his thoughts of this year’s conference, what he got out of all the events during the Malloy, and how it relates to his father, Allen Page, and Rodney’s own passion for the Negro Leagues.

He said the conference was his first-ever trip to Cooperstown and the Hall of Fame, and he said he definitely wasn’t disappointed and that the setting hit him on a personal level and that he felt a poignant connection to the Hall and to the sport of baseball via his father.

“It’s important to honor the soul of the game,” he said of the Hall. “We need to respect the participation of the individuals of the Negro Leagues and the respect the soul of the Negro Leagues.”

Regarding one of the conference presentations in particular, Rodney said he was thrilled that J.B. Martin IV attended the conference and gave a presentation about Martin’s great grandfather. He said his father, Allen Page, and the senior Martin were close business associates, adding that he was grateful to have known Martin Sr. through Allen Page.

“It was amazing to have been in his presence, and to hear his name so much,” Rodney said.

He added that the entrepreneurial spirit, determination and courage on the part of Allen Page and the Martins to survive and thrive in a segregated society was astounding and inspiring.

“All of the Martins and what they represented, for them to be so successful during Jim Crow, and facing the challenges for a Black man and a Black owned business …,” he pondered. “Think about what that represents, what it means.”

Regarding Allen Page, Rodney noted that his father owned multiple successful hotels, and he also gave a great deal of his time and money to help his community and the people in it. Allen paid folks’ hospital bills, for example, one of many ways Allen used his resources to assist others, efforts that earned him a famous (at least in New Orleans) nickname: “The Mayor of Dryades Street.”

“He helped a lot of people,” Rodney said. “That’s just the type of man he was. He was for the community, and for the people.”

Now that he’s retired, Rodney said he can focus more of his time on honoring his father’s legacy, spreading the word of what Allen – and his managers and players and business associates – was able to accomplish, and on delving even deeper into his father’s life. That includes hiring a professional genealogist to dig up more of the Page family tree and learn about where his father and the rest of his family came from and overcame.

Rodney added that he wishes more of the public would know about the Negro Leagues history of New Orleans, especially the contributions and impact of his father. He said he is amazed that knowledge of Black baseball in New Orleans still lags behind that of other cities, in the South and beyond.

That goes for the legacy of his father.

“It’s amazing that he’s forgotten, [despite] all he did for the city, and for the people of this city,” Rodney said.

To remedy that situation, Rodney simply wants to show people the greatness of his father and of Black baseball in the city.

“I just want to tell the truth about [his father’s legacy],” he said, “to tell the story.”

Rodney said that his father – like so many Negro Leagues legends – refused to buckle in the face of the immense challenges thrown at him by a bigoted, segregated and unjust society. Allen Page was a fighter, Rodney said, one who never, ever gave up.

“You can choose to be a victim, or you can choose to be a victor,” Rodney said, adding that seeing how African Americans like Allen fought back infused him with his father’s same unbending spirit.

“That’s what inspires me,” he said.

He added, with words that could apply not just to his father but to all of Black baseball:

“It’s a story of transcendence. To come from nothing and to persevere and transcend [Jim Crow], that’s the story. That’s his story.”

Epilogue: This article highlights only a fraction of all the good goings-on from the 2024 Malloy Conference, and encourage readers to read other articles, posts and other accounts from the week (such as here, here and here) as well as check out SABR’s official Negro Leagues Committee page!