Here’s an article I had published today about Herb Simpson’s brief time in Spokane six decades ago. Thanks as usual to Herb for being willing to sit down with me, thanks to my girlfriend Lori for going with me, thanks to Joe and everyone at the Spokesman-Review, and thanks to Bob Simeone and crew with the Mariners.

Uncategorized

Still waiting …

Herb Simpson, now (top) and then (below)

I just spoke with Herb Simpson, who recently became the first Negro Leaguer to be inducted into the New Orleans Professional Baseball Hall of Fame, and who, next month, will again be the guest of the Seattle Mariners for their annual African-American Heritage Day. Herb is the last known survivor of the 1946 Seattle Steelheads, and he was honored by the M’s last year as well, as the picture below (courtesy Mariners photo Ben VanHouten) shows:

During last year’s Mariners celebration, the team inducted into its Hall of Fame probably the greatest Mariner of all — Ken Griffey Jr.

But speaking of halls of fame … Herb Simpson, well more than a month ago, was, as stated, inducted into the NOPBHF, which is sponsored by the Triple-A Zephyrs.

It seems that at the time of the NOPBHF induction ceremony, Herb was promised that he would receive, within a couple weeks, a Hall of Fame plaque in his honor.

Well, as of this afternoon (Saturday), he’s still waiting for it, well more than a month after he was told it would be coming. In fact, he said just now that the Z’s told him he would be getting it today. But it’s 3 p.m., and the day is almost over.

But someone is recognizing Herb and his accomplishments. Below is a beautiful statement about Herb’s induction into the NOLA Hall by Rodney Page, the son of Allen Page, the local promotor, team owner and executive who was the towering figure over New Orleans blackball for decades.

Rodney has wonderful words for Herb:

In Honor of Herb Simpson

Congratulations, kudos and much respect are in order for the induction of Herb Simpson into the New Orleans Professional Baseball Hall of Fame. What an acknowledgement, recognition and accomplishment of a life well-lived. In many respects, Herb Simpson is a forerunner, a beacon of light, a chosen vessel stepping through a portal into the realm of recognized achievement, long overdue.

Hopefully, his induction will increase awareness and much deserved recognition of the rich, fertile, significant history of Negro Leagues Baseball in New Orleans. The evidence is unequivocal, undeniable and without argument – however best stated or received. From my humble yet authentic perspective, Herb Simpson is representative of deserving others who have made major contributions to New Orleans baseball history, and more specifically — New Orleans Negro Leagues baseball history.

Yes, I submit without reservation that there are others who, without question, meet the criteria for selection to the New Orleans Professional Baseball Hall of Fame: “citizens of greater New Orleans (birth or re-location), outstanding baseball achievement as a player, coach or administrator that has brought recognition to the Greater New Orleans area, and be of good character and reputation.” For this reality to be fully realized, diligent research is required along with a willingness to “look deeper” perhaps from a different perspective.

Herb Simpson, thank you for who you are! Thank you for your journey in life! Thank you for your baseball accomplishments! Thank you for the many you represent – the lives, voices, faces, and memories of those from the past (often overlooked, forgotten or unaware of) who were major participants and contributors in New Orleans Negro Leagues baseball history!

Herb Simpson, I am extremely happy for your recognition and success. I know that my father, Allen C. Page, would be also. You have brought significance and meaning to others along your chosen path. I hope to meet you in person someday.

Respectfully,

Rodney Page

May 26, 2014

Now that is a tribute!

The search for a Redding survivor continues, Part 1: The Fords

Cannonball Dick Redding

So it looks like Cannonball Dick Redding’s two siblings, Leon and Minnie, each died without having any children (as did Dick) after living most, if not all, of their lives in Atlanta (unlike Dick, the wandering ballplayer), which is where the trip of siblings were raised by their parents, Richard Redding Sr. and the former Laura Ford.

Minnie died in the ATL in January 1970 and the age of 82 never (apparently) having married, while Leon passed away without he and his wife, Jessie, having offspring. (I can’t immediately determine when exactly Leon died, but he shows up in the Atlanta city directory several times into the 1950s). And, of course, the Cannonball himself never never had kids with his wife, Edna. (Edna, by the way, appears to have remarried quickly after Dick died in New York’s Pilgrim State Hospital in 1948, to William Wortham, a wealthy real estate magnate in New York City.)

So Cannonball never had any children, nieces or nephews, which severely crimps our chances of finding a living descendant/relative who could shed some light on why the famed pitcher was committed to a Long Island psychiatric center and, perhaps more importantly, why and how he died there in 1948.

While ensuing posts will give an update on the other avenues of obtaining that info I’m taking — i.e. human sources, phone calls, emails, etc. — this one the next post will go via the documentation path to find out if Cannonball Dick Redding had any uncles, aunts or cousins, even distant, who could have been progenitors of a continuing family line …

Let’s begin with Dick’s parents, Richard Sr. and the former Laura Ford. The couple, according to an official marriage license — which lists Richard as “Rich Reddin” — was married March 3, 1883, in Washington County, Ga. (see below). The couple moved to North Butler Avenue in Atlanta sometime after that.

But it seems like Richard Redding Sr. might have been somewhat of a wanderer. The 1900 U.S. lists Laura Redding as a laundress and the widowed mother of Minnie, Richard Jr. and Leon. However, by the 1910 Census, Richard is back in the picture, listed as “Richard Reden” with wife Laura and daughter Minnie on Butler Avenue. Richard is listed as a laborer at the water works, Laura is a laundress, and Minnie is a hotel maid.

Significantly, though, the document doesn’t appear to include Richard Jr. (Cannonball) or brother Leon in the home. But Leon’s WWI draft registration card lists him, age 18, as living at his parents’ home on Butler Avenue as of September 1918. Dick’s draft registration has him already living in Chicago, pitching for the famed Rube Foster.

That brings us to 1920, when Richard and Laura are living alone, sans kids, at 198 N. Butler in Atlanta. By the 1930 Census, the couple, still alone, had moved down a block to 92 N. Butler. Richard Sr. died in Atlanta in February 1936, less than two years after his wife. Curiously enough, Laura Redding’s August 1934 obituary in the Atlanta Daily World identifies her as the mother of famous pitcher Dick Redding and as the daughter of the beloved late Moses Ford, but there’s no mention of her husband.

So let’s take another step back — Richard Sr. and Laura’s parents, i.e. Dick Redding’s grandparents. I’ve already written about Moses Ford, Laura’s father, who moved from his birthplace in Washington County to Atlanta, where he became a beloved figure at the post office. In that post, I detailed how Moses Ford, according to an Atlanta Constitution article after his death, was a slave born to the family of Georgia political power player J.W. Renfroe (who will get his own post here soon) and had, for some strange reason, allegedly never declared himself free.

Because he was born a slave in Sandersville, Washington County, it will be very tricky to track down Mose’s parents, or any siblings for that matter, because he doesn’t appear as a free man until the 1870 Census, when he’s listed as living with wife Harriet and daughter Laura, who would become Cannonball’s mother. Moses is listed as a “farmer,” i.e. sharecropper, aged 25 — which would peg his birthdate around 1845 — while Harriet is a 22-year-old housekeeper (i.e. birthdate 1848) and Laura is 8 years old (so birthdate of 1862) with no siblings.

In the 1880 Census (below), the 41-year-old Mose (which implies a birthdate of 1839, significantly earlier than the 1870 Census), a laborer, is listed with 40-year-old Harriet (so her birthdate is about 1840, also much earlier than the 1870 poll), a servant, and daughter Laura, 16 years old and at school (implying a birthdate of 1864). There’s probably no doubt that Moses and Harriet were born into slavery, while Laura would be a bit iffier, given that she appears to have been birthed during the Civil War.

Moses Ford appears in other contemporary documents as well, though … Like, for example, the voting registers. In July 1867, two years after the end of the Civil War and the adoption of the 13th Amendment, which abolished slavery, Moses Ford registered to vote in Washington County. Not surprisingly, given the fact that he was probably born a slave, Moses couldn’t write or sign his name and was forced to leave his mark, an X.

Moses also appears on several property rolls in the 97th Georgia militia district, Sandersville, under a list of freedman. Unfortunately, in each citation, he’s listed as owning very little, if anything, real property, but such is also the case with several of his neighbors and townsfolk.

The 1880 Census lists two more members of the Ford household. One is 4-year-old daughter Magness. Unfortunately, I can’t find any other record of her anywhere, at least online, so she might have died young, without any offspring or direct descendants.

The other person in the home is Moses’ brother, Cupid, who’s listed as 27 years old (so born circa 1853, probably in slavery). Cupid does show up in other Washington County documents, such as freedman registers, including two sheets on which he is listed very close to his brother. And, in July 1867, Cupid — written as “Cupit” — registered to vote in Washington County.

From there, there are no more records of a Cupid Ford in Washington County. There are, however, numerous ones — mainly city directories and death registers in Savannah, Ga. — that list an African American named Cupid Ford, married to Anna Ford and born around the correct time.

Finally, one freedman register from Washington County also includes a Cranford Ford close to Cupid and Moses, but that proved to be a dead end. Sooooooo, unless I can follow the one Cupid Ford in Georgia and trace some descendants of him, the Ford family — Cannonball Dick Redding’s maternal family — is a giant dead end, especially because it doesn’t appear that Moses and Harriet had any more children.

However, now, what about Cannonball’s paternal ancestry, the Reddings? Here I found a little more to go on, but ultimately, still can’t find any lineage paths to the present day.

What I can say is this: That the Fords and the Reddings in all likelihood knew other other. Why? Why, because the Reddings, including Cannonball’s grandfather, Henry, also lived in Washington County, Ga. In fact, Henry is listed on property rolls in the same militia district, the 97th, as Moses Ford. So both of Cannonball’s grandfathers lived in the same town, Sandersville, which means Dick’s parents, Richard Sr. and Laura Ford, could very well have grown up knowing each other.

I’ll explore the Redding side of Cannonball Dick Redding’s family in Part 2 …

Was the Cyclone Native-American?

(Illustration from Negro Leagues Baseball Players Association Website)

While my writing and research focus is generally on the Negro Leagues and other African-American baseball subjects, I’m also interested in other minority baseball history, which is reflected by (bragging ahead) recent articles in Jewish player Lip Pike and Jim Thorpe’s time on a team in Rocky Mount, N.C.

I’m especially keen on Native Americans in baseball, and when that subject intersects with the Negro Leagues … whew, I’m elated!

Such is the case with Hall of Fame pitcher Cyclone Joe Williams, who is often mentioned in the same breath as Satchel Paige for the title of greatest pre-integration black twirler ever. What fascinates me is the fact that most of the more extensive biographies of Seguin, Texas, native Williams assert that he is part Native-American. Most often he is reported as Cherokee, probably on his mother’s side, or occasionally he’s tabbed as part Comanche.

I spoke with Royse “Crash” Parr, a member of both SABR and the Cherokee Nation, this morning about Joe Williams’ possible Native-American ancestry. Royse said he believes that Cyclone actually had indigenous blood on both sides of his family. However, Royse added, “It’s never been confirmed that (Williams) was part Indian” and that he (Royse) is “pretty sure he’s not on any tribal rolls or anything like that.”

I asked Royse about the discrepancy between varies Cyclone bios regarding the pitcher’s exact Indian lineage, i.e. Cherokee or Comanche, and he said that “if I had to guess, it would be Cherokee.”

Now, there’s a significant historical and geographical difference between Cherokees and Comanches — while both modern, federally recognized nations are located mainly in Oklahoma, the two tribes have very different roots, certainly geographically and also culturally speaking. The Cherokees were originally from the southeastern part of the country and were one of the main groups forced out of their ancestral homeland on the Trail of Tears. That’s how the modern Cherokee Nation ended up in the lower Midwest. Comanches, meanwhile, were very spread out, covering parts of what is now Texas, New Mexico, Kansas, Oklahoma and Colorado.

So we have to consider that by the time Joe Williams was born, both the Cherokee and the Comanche had fairly large populations in Oklahoma and Texas, so Williams and his family could feasibly have been either. But, as Royse said, the most accurate guess is probably Cherokee.

A fair amount of research has been conducted into the details of Cyclone’s familial roots — by Gary Ashwill and others — with a lot of it focused on the fact, for example, that U.S. Census information, seemingly impossibly, has two Joseph Williams listed in Seguin in 1900. With a big assist from dedicated researcher/historian Bill Staples Jr., both Joes are listed as born in the 1880s, with one having a mother named Lottie and the other claiming a mom named Lillie.

Bill believes, with significant evidence from other official and circumstantial sources, that it’s the one listed as Joe William (as opposed to Williams) and born in May 1886 to Lillie William(s). According to that Census page (posted below), the entire family and their respective parents were born in Texas, and all of them are listed as black.

Unfortunately, though, no official documents have turned up that definitively confirm or refute the notion that Cyclone Joe Williams was part Native-American. But Bill Staples, whose father in law are a blend of several tribes, notes that, around the turn of the century, Native Americans were treated and viewed so poorly that even African Americans with indigenous ancestry found it “better to pass as 1005 black than to let others know that you were part Indian. The fact that many African Americans tried to hide or disown their Native American roots makes searches like Joe Williams’ and others even more complicated …”

In the end, Bill concludes, it might take locating a distant relative/descendant of Joe Williams so a DNA test can be performed that would, hopefully, conclusively determine the Cyclone’s true heritage.

That’s one of the mysteries associated with Joe Williams. In a future post (hopefully over the next couple weeks), I’ll try to address why Williams is buried in Maryland in the same grave as two other men who seemingly have no connection to him …

Thoughts on latest Sol White developments

Baseball researchers, including MLB official historian John Thorn and Jim Overmyer, have found a lead on possible descendants of Hall of Famer Sol White, who recently received a burial stone thanks to the efforts of the Negro Leagues Baseball Grave Marker Project. Here is a link to Thorn’s blog post on the matter, and check out some info on the marker ceremony here and here.

These developments and efforts regarding White’s legacy and possible relatives are fascinating, revelatory and quite possibly groundbreaking. A couple things strike me about this …

One, I’d have to imagine that if any living descendants are found, chances are that, given the previously futile efforts to find any such people, those relatives would have no idea they’re related to one of the most important and influential figures in baseball history. The revelation that Sol White is in their lineage could very well blow them away.

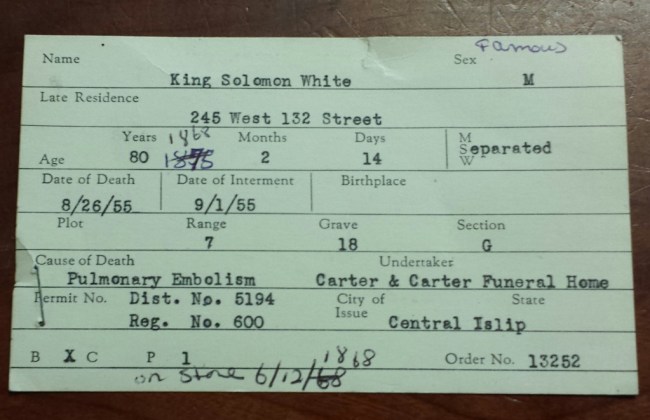

Second, with my efforts focused on the discovery of what exactly happened to Sol White to land him in a Long Island psychiatric hospital until his death, I’m ecstatic on one level, because the latest research developments unearthed this — a burial record, which lists his cause of death, “pulmonary embolism”:

A pulmonary embolism is basically a blockage of an artery or arteries in the lung, most likely by a blood clot that has traveled from the legs to the lungs.

What strikes me is the fact that, according to the Mayo Clinic Web site, pulmonary embolisms are very treatable and even preventable if proper, swift efforts are undertaken. On one hand, that makes me wonder if Sol received shoddy treatment at Central Islip State Hospital that could have contributed to a possibly preventable death. For example, what if he had surgery at CISH that led to the clot or clots that killed him. But on the other hand, he was 80 years old, so such a cause of death isn’t really all that unusual for a guy his age, especially six decades ago.

Overall, though, while the uncovering of this burial record and immediate cause of death is certainly crucial, it doesn’t reveal why Sol was in a mental ward or what the contributing factors were to his pulmonary embolism. Those are details that are included only in a complete, unredacted death certificate, a copy of which has yet to be obtained by anyone.

The other way of procuring such facts is through the obtaining of medical records from the hospital at which a patient was treated and/or died. That’s something I’ve been trying to do with both Sol and Cannonball Dick Redding, who died at another New York state psychiatric facility and about whose fate is even less known. I aim to change that, and I’ll post an update to my quest over the next day or two …

Ted Strong to get his due

Just got back from a trip to Raleigh for a wedding event. Apologies for not getting anything up on the blog for a while. I’m going to do my best to offer some thoughts tomorrow about Sol White (and possibly some more on Dick Redding).

In the meantime, here’s something I just did for the South Bend Tribune on Ted Strong Jr., who, like many, many other Negro Leaguers, is a fascinating figure:

The Speed league

In doing research for another story, I tripped over something called the Berkeley International League, a circuit in the late 1930s based in, yep, Berkeley, Calif., and encompassing much of the Bay Area.

Like the California Winter League, the BIL was integrated, albeit amateur, unlike the CWL. But what was truly unique about the BIL was the fact that it wasn’t just white (with one or more possibly Jewish) and African-American (like the Athens Elks and Berkeley Grays) teams. It also had Latino (like the Aztec Stars), Chinese (such as the Wa Sung Athletic Club, which an organization that still exists, quite thrivingly) and, reportedly, Japanese teams (although I found no immediate evidence of any Japanese squads, which isn’t to say there wasn’t any).

The BIL and, especially, its Asian teams, have been completely unexplored up until this point, with experts only vaguely recognizing the league and its member squads. But apparently some of the loop’s squads competed in the California semipro state tournament and even the prestigious national Denver Post tourney.

For example, Rob Fitts, one of the preeminent scholars of Asian-American baseball, says this via email: “I don’t know much about the SF area teams other than the first Japanese team dates to about 1902 and I believe was called the Fuji Club. I’m pretty sure that they never barnstormed outside of the area.”

That in and of itself is certainly fascinating enough. But once I did a little more reading about the BIL, I learned a great deal about the guy behind it — Byron “Speed” Reilly.

In reference to the BIL, the Oakland Tribune called Reilly the “president of the circuit.” A February 1936 article in the paper paints a colorful picture of a guy who was part executive, part team owner (the Grays and the Elks), part PR hustler and part journalist:

“Byron ‘Speed’ Reilly, who organized the league and has held the president’s chair since it started in 1928, believes this year will be the best.

“‘After a careful check, I found that we averaged larger crowds at our diamond in Berkeley, than any park in Oakland,’ said Reilly. ‘And if the application of the Mexican Aztec Stars is received, the circuit will truly be international and I believe we will again outdraw any other league during our summer season.’”

And Reilly wasn’t just about the BIL. He also served as a correspondent/reporter for African-American newspapers across the country, and he also worked as a promotor and booking agent for major musical and variety acts that came through the Bay Area.

In many cases, Reilly’s “articles” for newspapers were little more than gussied-up press releases for his teams, leagues or entertainment shows. (Such a situation was certainly not an anomaly in the world of blackball. Back East, Cum Posey and other representatives of various teams Negro Leagues teams acted as “reporters” for newspapers, which today would be seen as a massive conflict of interest.)

But, for as ubiquitous as Reilly was in California, he proves a difficult figure on which to get a handle. It’s unclear, for example, exactly where he was based — the Bay Area or LA — and it’s even difficult to pin down whether he was black or white!

Reilly appears to have originally been from the Sacramento area, the son of Philip and Laura Reilly — or, in some documents, O’Reilly or O’Reily. Reillyy seems to have then moved to Oakland in the Bay Area by the time the 1930 Census was taken. In that document, Byron is listed as being “Byron O’Reily,” black, a newspaper reporter and born in roughly 1905.

In the 1940 Census, Reilly is listed as “Byron O’Reilly,” 39 years old, still living in Oakland, a promotor of a “radio program” and … white! Here’s that Census record:

What?!?!

His wife, the former Vivian Sanderson, was a native of Oakland and born in about 1909. They were married on May 3, 1930 in Oakland. In the official marriage register, Byron’s last name is “O’Reilly.”

Before that, in the 1910 and 1920 Censuses, Vivian is listed as white. Here’s that:

But then, in the 1940 Census, Vivian is listed as … black!

Double what?!?!

In the report, the couple has two sons and a daughter, and they’re still living in Oakland in an otherwise largely white neighborhood.

To say the least, Byron “Speed” Reilly’s life and career were fascinating as well as perplexing. Why, for example, would he drop the O’ from his last name? And how do we explain the shifting racial identities of both him and his wife?

The answers to those questions could be many and varied, with some very possibly concerning the issue of “passing” for one race or another in order to fit in and adapt to whatever professional or socioeconomic circles in which they found themselves at any given moment. Perhaps both Byron and Vivian were extremely light-skinned mixed-race people who could, in fact, easily slip between ethnic identities.

And maybe because of that ambiguity, Byron O’Reilly became Byron Reilly because O’Reilly sounds more white (probably Gaelic), which he could have viewed as detrimental to his status in the African-American athletic, entertainment and social circles in which he traveled.

The exact answers to those questions might only be discovered if descendants/relatives of Byron and/or Vivian are discovered, located and interviewed.

Until then, one can only speculate and ponder on such shifting solutions. In any event, Byron “Speed” Reilly was certainly a colorful character and a perhaps more than just a fascinating footnote in the history if minority baseball.

Does Sol White have living relatives?

I wish I could have gotten this up earlier, but it’s been a rough week. I also wish I could explore this in greater detail in this post, but hopefully I can over the weekend …

Major League Baseball’s official historian, John Thorn, did a bunch of digging into the background of Sol White, a Hall of Famer who just received a gravestone via the Negro League Baseball Grave Marker Project. (For an article I did on the story, go here, and for a Larry Lester Web page on the event, check this out.)

Mr. Thorn could very well have found that White — who hitherto, as far as anyone knew, had no living descendants or relatives or, therefore, anyone to represent his family at the above-mentioned ceremony — might actually have some!:

As I said, I’ll try to process this over the next few days and get my thoughts on it up soon.

That sentence sounds very egotistical, I think. Comparing myself to John Thorn was not my intent. I just have a lot of ideas about this bouncing around in my noggin.

And did I use the word hitherto correctly?

Another sort of trailblazer

Once in a while I veer off from my normal path and explore other aspects of hardball history — or what Gary Ashwill calls “adventures in baseball archaeology” — that involve other ethnicities. It also helps — and see my previous post relating to this — that we have a “XXXXXXX Heritage and History Month” for just about every segment of society, which means I always have an opportunity to sell stories about other ethnicities.

Such is the case in May, which is Jewish American Heritage Month, and, as it happens, for a while I’ve been fascinated to the point of meshuggennah about the story of Lip Pike, the first known professional base ball (two words) player and, certainly, the first Jewish professional player and the first Jewish base ball superstar. So today I just had an article about him published in CityBeat, the alt-weekly in Cincinnati.

Here’s a sketch of Mr. Pike:

This post is dedicated to my dear friend and journalistic colleague David Hammer, who has taught me so much about Jewish culture and history and even, at one point, actively encouraged my desire to be a mohel. David has been always been there for me, for 17 years now, through thick and thin, and I’m very, very proud of him. Even though he recently went to the dark side — gasp! — TV journalism. But he’s a damn good investigative reporter, the best I have ever personally known. He’s also just the best person I’ve ever known, period. Thanks, man.

Off to Seattle — and an internal journey

It’s official! I’m going to Seattle in late July for the Mariners’ African-American Heritage Day so I can cover Herb Simpson (the dashing fellow above) being honored by the team for his status as the last living member of the 1946 Seattle Steelheads.

The RBI Club, the Mariners’ booster group, is finding me accommodations while I’m there, which will be July 24-28, and the club is providing a $200 travel stipend toward a shockingly cheap $350 round trip — and non-stop, I might add — flight from NOLA to the Jet City on, surprisingly enough, Alaska Airlines. It’s hard convincing many New Orleanians that Alaska is, in fact, a real place and not a product of fairy tales about this “snow” business.

I’m thrilled and beyond honored by this development, to be honest. Out of all the New Orleans media the Seattle club could have to whom the Mariners club could have extended this offer, it chose me, which is both flattering and humbling, and I plan to make the best of the opportunity.

I’m also extremely excited for Herb as well. When he makes the trip in a couple months, he’ll be just shy of his 94th birthday, so this will most likely be his last trip to Seattle for this annual fete. The rigors of travel are just too rough to go through on a yearly basis, despite the fact that he’s being accompanied by his nephew for help. Heck, flying is a stressful pain in the butt for my 41-year-old fanny, and probably for people of all ages.

While this is happening, though, I’m kind of having an existential crisis as to why, exactly, I do the work that I do. Because, at the heart of it, I’m a journalist first. I was trained as a journalist, I have two degrees in journalism, and I’ve spent the majority of my professional career as a news reporter/writer.

And on top of that, I’m a freelance journalist, which is basically the worst kind of journalist you could be, financially speaking. I’m dirt poor. Paying rent is a nail-biting trial on a monthly basis. And, as a result of such fiscal realities, freelance journalists, to be truly successful, have to be willing to write anything for anyone, within the bounds of one’s own personal ethics. (Yes, we journalists do have ethics.)

But at this moment I choose to fill a very specific niche — Negro Leagues (and, to a lesser extent, general minority sports history) journalism. I choose to focus on historical journalism because I have fallen in love with the research process of it. I love blending historical research with interviewing human experts and other sources to, I hope, create a product that presents history in a style and manner that is both appealing to research junkies and to the general public. That’s my task as an historical journalist.

But, as you can probably guess, convincing the average editor of a magazine or newspaper to commission an article on the Negro Leagues is, to say the least, a tough sell. “What’s the news hook?” “Why should this publication run this story now?”

So, no matter how deeply I, as a historical researcher, am enthralled with a certain subject — say, this topic — to a sports editor at the LA Times, the reaction is, “So what? Who cares about a single game that took place three-quarters of a century ago on the fringes of baseball? Why is that important to our readers now? Get outta here, dork, you’re buggin’ me.”

Therein lies the crux of the problem: If historical research I do won’t bring me an assignment and, therefore, income, should I continue doing it? Is it worth proceeding with the work for the sake of the work and for my love of it? Or do I bag it and pitch articles about town board meetings and school beauty pageants? What’s more important: Paying the bills or doing what I love?

It’s unfortunate that quite frequently that’s what my career comes down to a various points. And I hate it. It tears me up on just about a daily basis.

So what does this have to do with my impending trip to Seattle with Herb Simpson? Actually, I’m honestly not really sure. I’m really not. Or rather, I can’t put it into words. I can’t explain it or even consciously make sense of it.

What I do know is that Herb Simpson is an incredible, inspiring man, and every time I’m in his presence I feel honored and humbled. And I’m psyched about going to Seattle, just because it’s quite a humbling honor (notice a running theme here?).

But make no mistake: I will try to make as much money as I possibly can from my voyage to the Pacific Northwest. I’ll hustle like hell to see as many stories about the event to as many publications as possible. The trip is thus both a sign of how much I’m respected and liked as a writer and a researcher, but also a chance to make beaucoup bucks so I can pay my cell phone bill. The data overages just kill me.