I am seemingly going to the end of the earth — or at least the limits of Ancestry.com — to somehow find any living descendant/relative of Cannonball Dick Redding (above, via www.mlb.com). To be honest, it’s driving me bananas. It’s seriously making my head spin. I’m reduced to maybe trying to find a descendant of Dick Redding’s widow’s second husband — if he was even her husband at all.

Dick Redding and his wife Edna didn’t have children, and apparently neither did either of his siblings, Leon or Minnie. Since Dick Redding is buried in Long Island National Cemetery — he served in the Army during WWI — I called the cemetery offices to see if they might have any sort of death record, and they claimed they didn’t. And it’s extremely difficult getting personnel records out of the U.S. military.

As a matter of fact, just now I tried calling the LIN Cemetery again and asked if there was any way they would have records of cause of death for a veteran. I was told, rather tersely, that no, national cemeteries don’t ask for death certificates or anything like that. They just need proof that he (or she) was a veteran, and that’s good enough for them. “We don’t require death certificates,” this soldier told me. “Those are the property of the family.” So I guess that’s that.

Anyway, I also took a flyer and tried looking up the last name Redding in the Atlanta white pages … only to find there’s more than 100 Reddings listed. So I then attempted to find anyone in the city of Atlanta government or administration named Redding. No luck. I guess I can try the Atlanta Chamber of Commerce, the local African-American museums and/or the Atlanta SABR chapter.

Gary Ashwill has graciously helped me try to procure death records for Redding from New York State, so we’re holding out hope that will turn out well. However, having been born, raised and lived in New York State for much of my life, it’s still hard to fathom the ineptitude and inefficiency of the NYS government bureaucracy.

While I try to sort all this how … somehow … I am finding out some fascinating stuff about Dick Redding’s family roots. That means, namely, his maternal grandfather, Moses Ford. Some backstory …

I’ve found very little out about Cannonball’s paternal side of the family. The pitcher was a Junior — his father was Richard Redding, or some variation thereof (in the 1910 Census, for example, he’s listed as Richard Reden).

But that’s as far back as I’ve been able to go. Richard Sr. was born in (roughly) 1855, so he was most likely a slave at birth. He married Cannonball’s mother, the former Laura Ford, on March 3, 1883, in the Washington County, Ga. (The marriage record spells Richard’s last name as Reddin.) Washington County is a fairly rural county in east central Georgia. The county seat is Sandersville.

Sandersville is the hometown of Laura Ford, Cannonball’s mother. She was the first child of Moses (or Mose) and Harriet Ford. The 1870 Census states that Laura was born in roughly 1862 — so, again, she was in all likelihood born into slavery. Here’s that record:

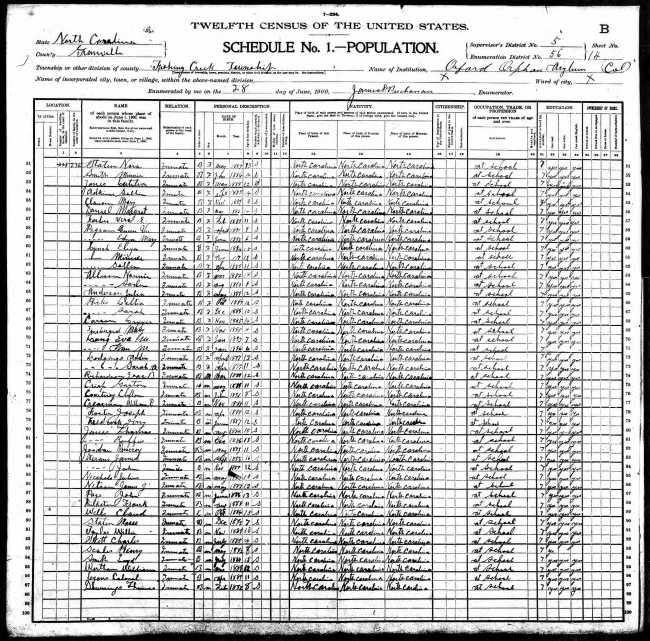

That Census record reports that Moses Ford was born in about 1845, while Harriet was birthed about three years later. Moses is listed as a “farmer,” i.e. a dirt-poor sharecropper. The family is also listed in Washington County in the 1880 Census, with Mose a “laborer” and Harriet a “servant.”

But then Laura Ford married Richard Redding Sr., and the whole clan moved to Atlanta. Because the vast majority of the 1890 Census was destroyed by fire, the next time the Reddings turn up in the Census is 1900, and there’ a little oddity at that point. The 1900 document lists Laura as a single mother of Minnie, Richard Jr. and Leon on Ellis Street. I couldn’t find Richard Sr. in the Census.

But then, in 1910, Richard Sr. is back with the family. Richard Jr. — Cannonball — was born in 1893 (or 1895, depending on what military record you’re looking at).

But to me, the most intriguing part os what happened to Moses Ford, Cannonball’s maternal grandfather. When he came to the ATL, he settled on Houston Street, presumably with Harriet. He got a job as a janitor at the local post office, where he proceeded to become a long-serving, beloved figure in the USPS.

When Moses Ford died in early March 1918 — just about the time his famous grandson was heading off to war in Europe — the Atlanta Constitution ran a glowing obituary about “Uncle Moses”:

The story was a lengthy four paragraphs long, an amount of ink that, at the time, was unheard of for a major white metropolitan daily. That the paper even mentioned the death of a “common” black laborer was stunning. But the fact that the publication gave so much space to the death of an African-American janitor is incredible.

The article, of course, while earnestly trying to offer praise to a black man at a time when lynchings in Georgia were commonplace, is laced with an underlying and subtle paternalism and recalcitrant racial superiority that identifies “Uncle Moses” as what would have been called, at the time, “a good Negro.” Here’s the first paragraph:

“There was real grief in all the departments of the Atlanta postoffice yesterday when it was announced that old Uncle Moses Ford had ‘gone where the good darkies go,’ and scores of the old attaches of the service were not ashamed of their tears.”

OK, that paragraph is just, just … loaded with such … Set aside the fact that the article called this supposedly beloved figure a “darkie” is appalling enough. But it also implies, quite insultingly, that there are two heavens — one for whites and one for the “good Negroes” who toe the line and, essentially, “know their place.” If you do that, then you’ll be lucky enough to go to darky heaven.

“Uncle Moses,” the article continues, “had been a faithful employee of the postoffice for more than a quarter of a century and all were proud to call him friend.” The article then reveals that Moses Ford had been a slave of the Renfroe family and “had never declared himself free.” I’ll give you time to slap your forehead in amazement.

Moses was appointed to the position of janitor by Col. J.W. Renfroe when the latter began serving as postmaster, and “Uncle Mose” went on to serve under seven postmasters.

However, the last paragraph is actually somewhat encouraging and heartening to the modern reader, because it offers some insight into the level of what seems to be actual, true respect for and trust in Moses Ford on the part of his white employers and colleagues:

“Old employees state that he had probably carried millions of the government’s money to the banks, as it had been the custom for years to accompany the cashier and help carry the deposits and many officials had been in the habit of getting Uncle Mose to do their banking business for them.”

The memory of Moses Ford was also long-lasting in Atlanta. When Moses Ford’s daughter (and Cannonball Redding’s mother) died in August 1934, the Atlanta Daily World, an African-American paper, ran a short story under the headline, “Former Local Baseball Star Loses Mother.”:

In addition to offering some fascinating nuggets about Dick Redding’s youth — he was “somewhat of a colored mascot for the Atlanta Crackers and was well known for his pitching ability. … The management, at one time, it is said, deplored the fact that ‘Spaniard’ was a black boy and could not use him in their games” — the piece also recalls Moses Ford:

“Mrs. Redding is the daughter of Mose Ford, once a popular janitor at the United States Post Office here. Mr. Ford was affectionately called ‘Uncle Mose’ until his death.”

Ultimately, does any of this reveal any new avenues of investigation to find any living relatives of Cannonball Dick Redding? Most likely not. But another intriguing question is how much Cannonball knew about his familial roots, including his much honored grandfather, “Uncle Moses” Ford.

By all appearances it looks like Dick Redding left Atlanta — and possibly his family — for the baseball big-time and never looked back. I suppose he couldn’t be blamed for such a decision if he made it. Why associate with a place where your grandfather, despite (allegedly) gaining the love, respect and trust of the white powers-that-be, still be called a darky?