Karma. Existential justice. Reaping what you sow. Bad juju.

Whatever you want to call it, it seems like it might have been at play following the law-enforcement lynching of African-American baseball team owner Fred Goree a century ago.

The two deputies who speciously pulled over Goree’s new Cadillac – in a fairly obvious case of “driving while Black” – walked him from the car, and beat him to death, later claiming that it was Goree who began attacking them.

When St. Louis (Missouri) County deputy constable Clarence Edgcombe “Pat” Bennett and a companion, Charles Schuchmann, murdered Goree on Aug. 1, 1925, as Goree and friends were in the St. Louis area for a game featuring the Chicago Independents, Goree’s team, the two officers just might have invited fate to turn against them.

After an investigation, a St. Louis County coroner’s jury exonerated Bennett directly and Schuchmann implicitly of any blame for the killing of Goree; the jury apparently believed Bennett when the deputy testified that Goree attempted to grab Bennett’s gun when the baseball owner was shot. This despite the testimony and assertions of other witnesses that Goree’s skull was, in fact, crushed and he was actually on the ground when he was shot.

Even though the deputy constables escaped the legal system more or less unscathed, the universe, perhaps, wasn’t quite pleased.

Because within four years, both Bennett and Schuchmann ended up the victims of gun violence – the former having his jaw shattered when shot in the face by alleged robbers, the latter dying from what Schuchmann’s death certificate called a “gunshot wound in head [during an] unavoidable accident.”

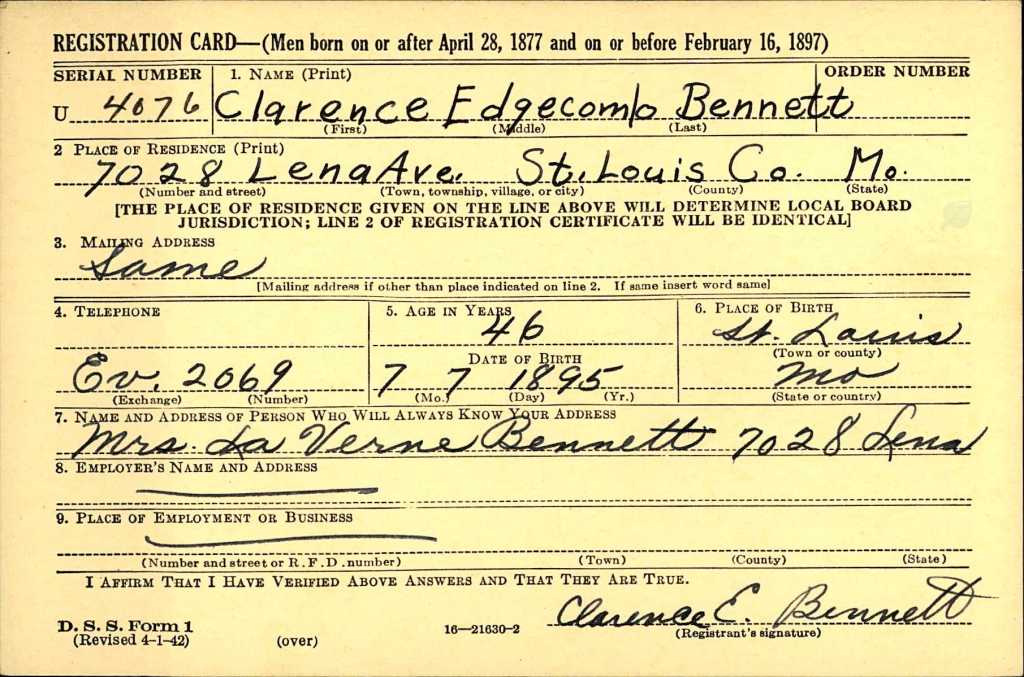

Bennett was born in St. Louis in 1895 to Clarence Edgcombe “Clay” Bennett Sr., a foreman at a printing press, and the former Amelia Graham. Clarence Jr. was one of 11 children in a family that at first lived in the City of St. Louis but later moved to St. Louis County.

(It’s important to note that St. Louis County was at the time and still is separate and distinct from the City Of St. Louis, which split off from the county in the 1870s. This fact made it a bit challenging to do research for this series on Fred Goree.)

Clarence Jr. – for the sake of clarity, I’ll refer to Bennett Jr. as Pat from here on out – as a cook in the Army during WWI; he was reportedly wounded and gassed during battle while a part of the 138th Infantry, Missouri National Guard.

Bennett became a deputy constable in 1922, roughly three years before killing Fred Goree. He was appointed a deputy sheriff in 1936 by St. Louis County then-Sheriff-elect A.J. Frank, under whom Bennett served until 1941. Bennett unsuccessfully ran for St. Louis County Sheriff in 1952 as a Republican while he was working as an ironworks foreman. Bennett had also previously and unsuccessfully run for justice of the peace in St. Ferdinand Township in 1930.

Bennett married Emma Lovern (or LaVerne) Hartung (nee 1906) in 1925 in Bond County, Ill., which is just over the Mississippi River from St. Louis. The couple lived in St. Ferdinand Township, part of St. Louis County, for much of their lives and had one child, a daughter, Donna Rose, who was born in 1931.

The family later moved to the City of Jennings in St. Louis County.

Pat and Lovern then moved to the Tampa–St. Petersburg area in Florida, where Pat died in 1971 at the age of 75. (Lovern then might have moved back to the St. Louis area, where she died in 2001.)

Perhaps significantly, Pat’s obituaries (from both the St. Louis Post-Dispatch and the Tampa Bay Times) make no mention of his career in law enforcement.

And it’s back to his time as a constable we now go, because what happened to him after the murder of Fred Goree is pretty stunning – namely, being shot in the face while reportedly fighting with a trio of robbers.

According to reports in the Post-Dispatch and Globe-Democrat newspapers, the incident occurred in the wee hours of the morning on May 12, 1926, when Pat Bennett, accompanied by his brother, Grant (who was unarmed and not a constable officer), reportedly witnessed three suspicious men approach another vehicle that was parked on the side of the road and that contained two men and two women.

The Bennetts reportedly grew suspicious of the trio of men as the three men approached the other, parked vehicle and allegedly searched the two couples. The brothers – Pat had his gun in his hand – got out of their vehicle and attempted to sneak up on the suspected robbers, who nevertheless allegedly saw the Bennetts. One of the suspects shot twice, with one of the bullets hitting Pat in the face. The alleged robbers abandoned their car and fled on foot, while Grant Bennett and the occupants of the other vehicle (the potential robbery victims) assisted the wounded Pat and took him to get treatment. The car used by the suspects allegedly had been stolen from in front of a residence earlier in the night.

The bullet had struck Pat Bennett in the nose and split into three fragments, two of which lodged in his jaw. The third exited his left cheek. He was reported by the Post-Dispatch in serious condition at St. Mary’s Hospital.

Both the article in the Post-Dispatch and the one in the Globe-Democrat mentioned the previous year’s incident in which Goree was killed and noted that Pat Bennett had been exonerated in the killing.

The only follow-up information that I could find about the 1926 incident was from an article in the May 15, 1926, issue of the St. Louis Star and Times newspaper, which reported that one suspect, Raymond Hogan, in the shooting of Pat Bennett had been arrested. Hogan was the son of notorious gangster Edward J. “Jellyroll” Hogan. I wasn’t able to find any further information about Hogan’s case.

As of the May 15 article, Pat Bennett was still in critical condition at the hospital, but he obviously recovered eventually and continued his career in law enforcement.

Schuchmann wasn’t so lucky, however.

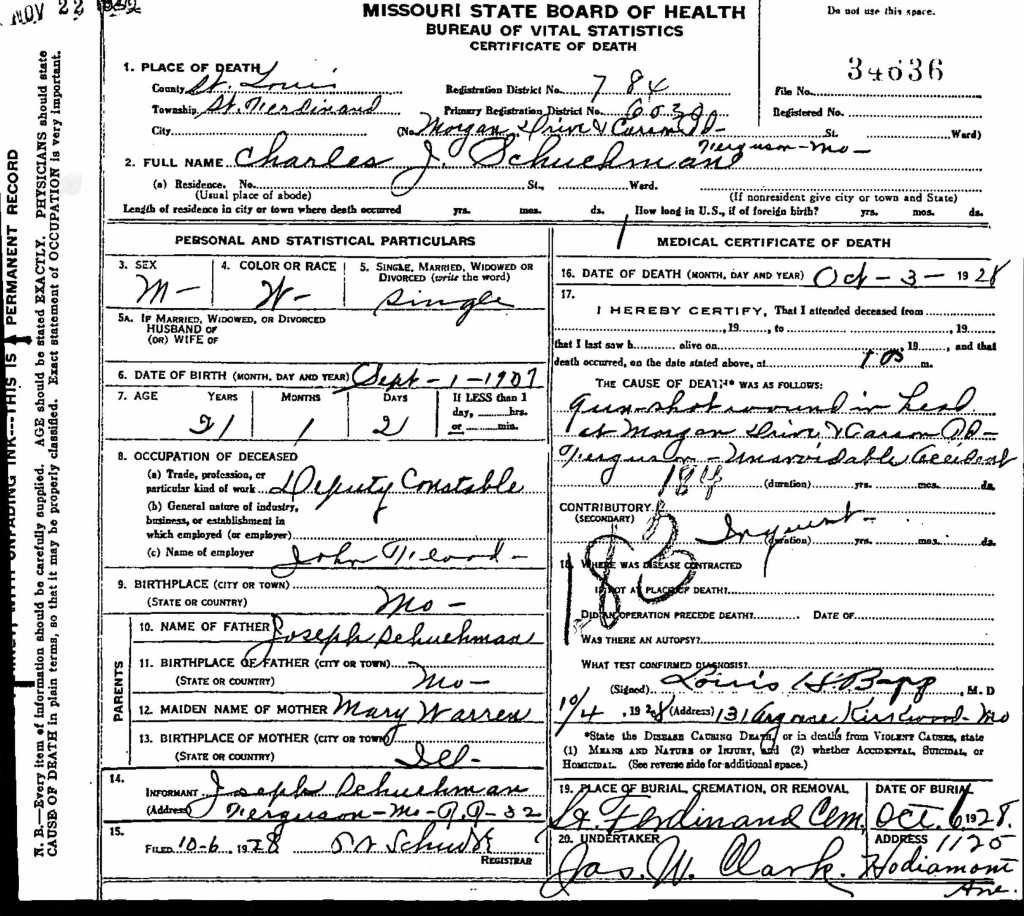

Before we get into his fate, let’s take a quick look at Charles J. Schuchmann’s personal background. He was born on Sept. 1, 1907, the seventh child of Joseph J. “Jesse” Sr. and Mary (nee Weirman or Wierman) “Dolly” Schuchmann, who had nine children total (five boys, four girls).

The Schuchmann family traced back to the Baden-Wurttemberg region of what is now Germany; numerous members of the clan emigrated from there to the U.S. in the early-to-mid-19th century. Several Schuchmanns worked as either butchers or grocers/food peddlers; on the federal Census, Jesse was listed as a butcher in the 1900 and 1910 editions, and as a “huckster” in 1920 and 1930 (specifically selling vegetables in the latter).

Charles’ maternal grandmother was the former Louisa (or Louise) Dehatre, part of the DeHatre family of St. Louis. The DeHatres were one of the earliest families to settle in the area, stretching back to the late 1700s, and they owned several prominent businesses in and around St. Louis.

Charles Schuchmann’s precise role in Goree’s death is somewhat unclear, but by most accounts he was actively involved. According to Bennett’s testimony in a coroner’s inquiry following Goree’s murder, Goree had reached for Bennett’s gun during a scuffle during the roadside stop.

“The negro was getting the best of me,” Bennett told the coroner’s jury, as reported by the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, “and I called to Schuchmann for help. He ran to me and struck Goree twice on the head. Goree’s grip on the revolver relaxed and I told Schuchmann not to hit him again.”

Bennett testified that the gun then went off in the scuffle, with the shot reportedly striking Goree. The deputy said that he (Bennett) succeeded in wresting the gun from Goree and shot at the victim twice, both hitting Goree, who died a little while later while receiving treatment.

However, the St. Louis Argus, an African-American newspaper, reported a different account of what actually transpired.

“The reports of several eye witnesses of the slaying … have given plain evidence of a case of cold-blooded murder … and local white dailies failed to present facts to show that [Bennett] was in the wrong,” stated the Aug. 7, 1925, issue of the Argus.

The newspaper cited testimony by Goree’s two companions in the Buick, Frenchie Henry and Harold Gauldin, that directly contradicted the accounts of Schuchmann and Bennett.

The trio of Black men – who were on their way from the St. Louis area to Effingham, Ill., to pick up members of Goree’s team who’d been stranded in the latter city on their way to the team’s scheduled game in the St. Louis suburbs – weren’t the aggressors in the confrontation, Henry, Gauldin and other witnesses said.

The witnesses reportedly stated that Bennett seemed drunk and became infuriated when Goree pleaded with Bennett to let the team owner make arrangements for the safe retrieval of the players in Effingham. The witnesses further reported that upon losing his temper and calling Goree a “damn n*****,” Bennett drew his gun – the white men had testified that Goree had suddenly reached for Bennett’s gun out of the blue – and when Goree grabbed hold of the gun in self-defense, it went off during the ensuing struggle.

According to the witnesses, Bennett then did call to Schuchmann for help, and Schuchmann did rush to Bennett’s aid. But while Bennett had testified that Schuchmann had “struck Goree twice in the head” before stopping on Bennett’s order, the witnesses gave a starkly different account. Stated the Argus:

“[T]he youth came and beat Goree over the head with a black jack for a period which Gauldin estimated lasted three minutes [itals mine].” The article further asserted that post-mortem examination found 15 lacerations on Goree’s head and that “his skull was crushed.”

The Argus stated that according to their witnesses, Goree then appeared to lose consciousness, at which time Bennett dismissed Schuchmann back to the patrol car and proceeded to shoot Goree’s prone, unconscious body twice.

While the coroner’s just obviously and basically dismissed Gauldin’s and Henry’s accounts out of hand, the pair’s statements paint a much more damning picture of Schuchmann’s role in the murder.

That is especially galling given that exactly why Schuchmann was accompanying Bennett isn’t clear. He was just shy of his 18th birthday and, evidently, not connected with the Constable’s Office or law enforcement in any discernable way, or at least not at that point. He apparently did, in fact, become a deputy St. Louis County deputy constable, which was his listed occupation on his death certificate a little more than three years later.

In fact, Schuchmann was a deputy for the St. Ferdinand Township constable’s office, a position you would think would require a decent knowledge of firearm safety, but apparently Schuchmann missed that day of training because he appears to have been quite careless in the incident that killed him.

According to ctestimony from Charles Schuchmann’s younger brother, Jesse Jr., the two brothers, along with a third brother, Phillip, were target practicing with their revolvers near the Schuchmann home in St. Louis County, during which Phil and Jesse placed a bottle on a tree stump and were shooting at it. At some point, Charles approached the stump to examine if a bullet had hit the bottle (it hadn’t), apparently doing so right when Jesse had squeezed off a shot.

Since I don’t own, shoot or know much about guns – I think the last time I used a firearm was 40-ish years ago at the rifle ranch at Boy Scout summer camp (I enjoyed archery a lot more than those stupid rifles) – I’ll quote directly from the account in the St. Louis Globe-Democrat of Oct. 4, 1928:

“As [Charles] spoke and before he had time to move away, the pistol which Jesse held was discharged and the bullet struck Charles in the mouth. Jesse said he was not aware that an automatic pistol was self-cocked and had not realized he was pressing on the trigger.”

Charles was rushed to a hospital but was DOA – he was 21 years old – and Jesse was held on bond for an inquest the following day. The 24-year-old Jesse was cleared of any guilt when the coroner’s jury ruled the shooting an accident.

Charles was buried in St. Ferdinand Cemetery in Florissant, a suburb in St. Louis County. His death certificate listed a date of death as Oct. 3, 1928, and gave the cause of death as “gun-shot wound in head … unavoidable accident.” It might not have been avoidable, but it does seem like it was careless, at least more so than what a law-enforcement officer would display.

So, again, whether what happened to Clarence Bennett and Charles Schuchmann, respectively, was a matter of karma or simple coincidence probably depends on each reader’s more existential beliefs in how life operates. Do you think they were cases of poetic justice or just coincidence?