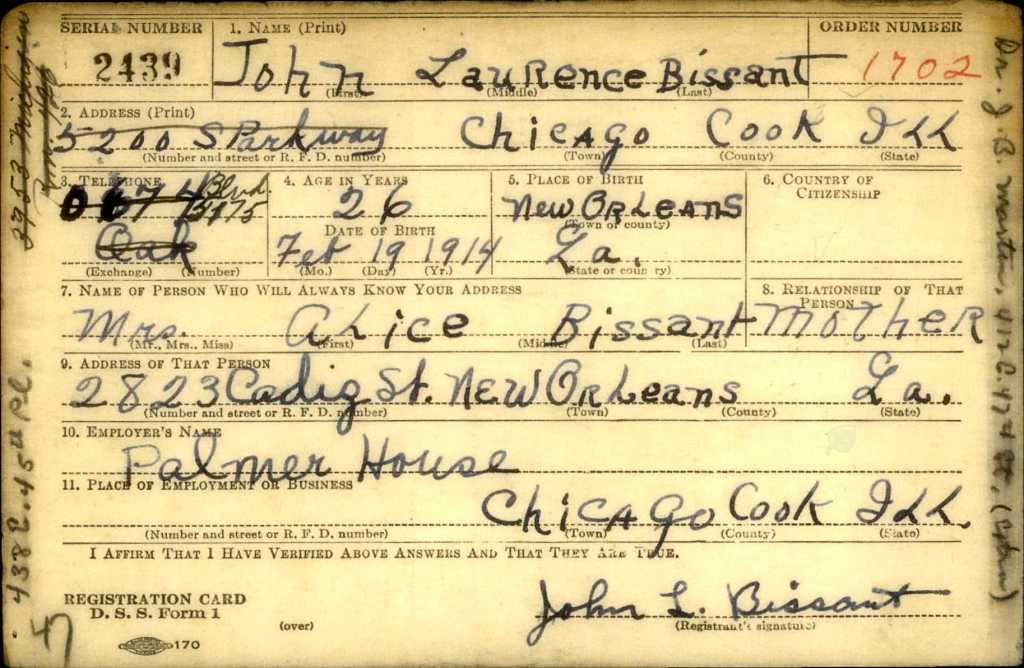

Since the beginning of this year, I’ve been in contact with Charisse Wheeler, a New Orleanian and the granddaughter of local Negro Leagues great John Bissant. I originally broached the subject of Bissant on this blog a few years ago with this post, about the ramshackle, anonymous nature of his grave in Carrollton Cemetery.

The cemetery, located in the Carrollton/Uptown neighborhood of New Orleans near the main campus of Tulane University, was historically divided into white and Black sections; the white area took up the vast majority of the graveyard, with people of color related to a small corner of the area.

Not surprisingly, the white section is today a much cleaner, nicer, and well maintained one than the Black section, much of which is untended, shambling, muddy and filled with many graves that include more than one family member.

While the white section includes numerous spacious, gleaning, well-kept crypts and mausoleums, the area for people of color contains many simple headstones, many of which are titled, toppled or askew. A lot of the stones are so eroded and obscured by nature that the names are practically illegible, rendering the graves’ occupants as essentially and sadly anonymous in death.

Such is the case with John Bissant’s grave, located on a family plot in the Black section. Resultantly, I’ve hoped that John’s grave could be the subject of another effort by the Negro League Baseball Grave Marker Project, but because his grave contains multiple people and cannot be specifically and conclusively located, it makes for a tough case for the NLBGMP.

I’ve also hoped that I could attract the attention of various local media in publicizing the location and ramshackle status of Bissant’s final resting and, by extension, the entire “colored” section of the cemetery.

However, it’s proven a difficult road to getting any articles or pieces undertaken on the local Negro Leagues, aside from The Louisiana Weekly newspaper, which has been gracious enough to publish several Negro Leagues stories of mine, such as this one about Creole Pete Robertson, this one about John Wright and this one concerning Gerald Sazon.

(Most media types to whom I’ve reached out here have either ignored me or come up with excuses why they can’t be bothered, namely the supreme, unquestioned importance of the Saints and LSU football. Some have also been quite hesitant to do on-air pieces because I’d have to be interviewed on camera, and my stuttering has also served as a convenient excuse for not doing so.)

Soon after my original post, though, Charisse posted a comment on the post introducing herself and saying she’s liked my work. We’ve since traded emails and messages and hope to talk in person or over Zoom soon.

But in the meantime, Charisse has filled me in on some stuff she and her family have been doing to honor John Bissant and his contributions to baseball history and to the city of New Orleans.

In particular, the family gathered to celebrate John’s life on Resurrection Sunday (Easter) this past April. In addition to Charisse, one of John’s sons, Lawrence Bissant, also attended, as well as several other grandchildren, a great grandson and a great great granddaughter. They also had jerseys and shirts made up.

“We still very much keep him and his memory alive,” Charisse told me via email.

She added: “We still very much talk about our grandfather and the many memories we had with him. I actually have a box of letters, where people would write [to] him from all over the world to get his signature.”

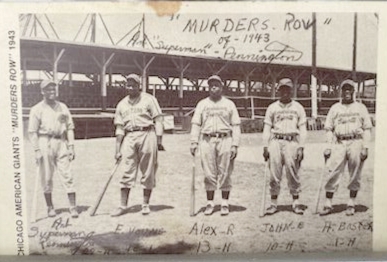

Bissant’s most prominent stint in Negro Leagues baseball came with the legendary Chicago American Giants, from 1939-1947. At that point, the G-men were members of the Negro American League and a decade or so removed from their greatest era in the 1920s under Rube Foster and then Dave Malarcher.

Beginning in 1937, the American Giants were owned by Dr. J.B. Martin, a dentist from Memphis who owned the Memphis Red Sox before shifting to the Windy City. He also served as president of the NAL. Unfortunately, the American Giants were largely mediocre at best during Bissant’s tenure with the club, never winning the NAL pennant and finishing last a whopping five times.

However, that American Giants club of the mid-1940s was, at times, fairly stacked. At various times Bissant’s teammates included standouts like Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe and Duty’s brother, Alec/Alex Radcliffe; Art “Superman” Pennington; Gentry Jessup; Walter “Rev” Cannady; Lester Lockett; Willie Cornelius; Ted Trent; John “Mule” Miles; John Ritchey; Lyman Bostock Sr.; and fellow New Orleanians Billy Horne and Lloyd “Ducky” Davenport.

As it turned out, as an outfielder, Bissant had the good fortune to team with other standouts – including NOLA lad Davenport – to form fearsome lineups in the outer garden for the American Giants. In June 1943, an Illinois paper noted that Bissant and Davenport were joined by Art Pennington in an “outfield [that] is considered the best in the [NAL].”

Actually, during and after Bissant’s playing career, newspapers often referred to Bissant together with Ducky Davenport as a duo of greatness; because both of them were outfielders from New Orleans – they competed against each other in high school here – and were both speedsters who prowled the outfield for the American Giants, it was natural to mention both in the same breath.

However, even then, Bissant garnered the highest praise, partially because he was so well rounded as an athlete.

“Bissant was a natural, as was Davenport,” stated the Louisiana Weekly in April 1970, “but [Bissant’s] wonderful physique, speed and power gave him the advantage, and his best sport was probably football, although he lettered in track [and] basketball, as well as baseball and football.”

Anyway, those CAGs aggregations also included, at different times, numerous Black baseball legends who were in the latter stages of their careers, including Willie Wells, Pepper Bassett (a Baton Rouge native), Jimmie Crutchfield, Chet Brewer and Cool Papa Bell. In addition, several esteemed veterans served as American Giants managers during Bissant’s stints with the club, including Ted Radcliffe, Bingo DeMoss and Candy Jim Taylor.

In 1996, writer Ross Forman interviewed Bissant for an article in “Sports Collectors Digest” magazine, and the piece chronicled a great deal of Bissant’s memories and recollections about his career and some of the Black baseball stars with whom he played, with a focus on his time with the CAGs.

“We had a lot of traveling experiences, meeting other clubs,” Bissant told Forman. “They were very fond memories of the Negro Leagues. I guess the highlight of my career was the year [the Chicago American Giants] made me captain of the team. We had quite a few young ballplayers coming in then and, to be a leader on that ball club was quite an honor.”

Bissant said that in the Windy City, “In Chicago, I think I was quite a hit with the fans because I hit really well. At the time when they took me, I had been playing infield, they turned me into an outfielder.”

Bissant added that traveling the country remained a career highlight.

“I still remember playing in the major league ballparks, such as Yankee Stadium and Polo Grounds,” he said. “That was nice. We also played in some small parks, some very small parks, places that never would compare to a major league stadium. My favorite was Comiskey.”

John’s career, while not as stellar as other Black ball legends who are waiting for induction in Cooperstown like Dick Redding and Rap Dixon, was certainly successful enough to make him one of the best baseball products of New Orleans, white or Black — a fact that requires his induction to the Louisiana Sports Hall of Fame and the Greater New Orleans Sports Hall of Fame at the very least. While spending most of his career as an outfielder (playing in all three outer garden positions at different times), he could also man second base and even take the mound if needed.

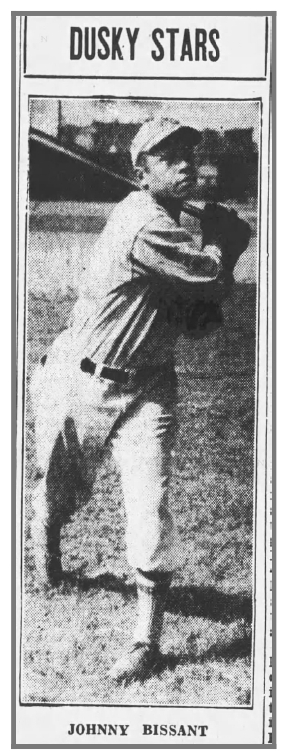

According to James A. Riley’s exhaustive book, “The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues,” Bissant batted and threw right-handed, stood at 5-foot-8 and weighed 180 pounds. Riley wrote that John was “[A] good outfielder [who] could run and throw, but is probably better known for his hitting.”

Newspaper writers also described Bissant as a standout with all-around talent and adaptability. A July 1944 article in the Belleville (Ill.) News-Democrat, for example, called Bissant “the team’s ace outfielder, and is a hard hitter as well as a great ground-coverer.”

The South Bend, Ind., Tribune, in previewing a game between Bissant’s Chicago Brown Bombers and a northern Indiana semipro team, offered a concise but glowing estimation of the New Orleans legend. At the time Bissant was usually stationed in left field.

“Bissant is tagged as the fleetest of the Bombers’ outfield,” the newspaper stated. “Because of his fleetness he sometimes patrols center giving the Bombers added protection on the strength of Bissant’s ability to roam into right or left to haul down apparent hits. He is death on [the] bases and specializes in base thievery to the chagrin of rival catchers.”

According to Seamheads.com, across all or parts of eight seasons in the major Negro Leagues with the Cincinnati Tigers and Chicago American Giants between 1937-47, Bissant played in a total of 139 games, amassing 477 at bats, with 74 runs, 131 hits, 16 doubles, nine triples, two homers, 44 RBI and nine stolen bases, showing that he wasn’t really a power hitter and wasn’t quite speedy enough to swipe bases by a pile like Cool Papa Bell and Sam Jethroe, but he slapped out hits at a very solid clip. His BA/OBP/SLG/OPS line was .275/.323/.358/.681.

“I don’t brag on myself,” Bissant told Forman. “I leave that to other people to do that, and staying up there in the lineup for most [of] my career was an honor. …

“I was a decent hitter, very fast; I stole quite a few bases. I can’t remember yoo many catchers stopping me. Sure, I was thrown out (trying to steal), but not any rash of stolen base tries. Most of the catchers when I played, had very good arms, not like the catchers now.”

He said he had a good relationship with fans, including those in Chicago.

“I think they appreciated my effort, and I enjoyed baseball,” Bissant said.

Unfortunately, Bissant was one of hundreds of Black players who never got a chance to compete in so-called Organized Baseball; he noted that “[W]hen they started taking Negro Leaguers into the major leagues, I was too old.”

But, even in his later years, the memories of his time in Negro League baseball remained sharp and sweet.

“Yep, it’s been over 50 years, yes indeed,” he told Forman, “even though I sometimes remember things like they happened yesterday.”

After retiring from baseball, John Bissant worked at several jobs in the New Orleans area, including at NASA’s Michoud Assembly Facility; Lykes Brothers Steamship Company, a shipping business; Glazer Steel and Aluminum; and a security guard firm.

John Bissant died on April 1, 2006, in Houston, Texas, at the age of 92; he had evacuated to Houston from New Orleans because of Hurricane Katrina. In its obituary of Bissant, the Times-Picayune called him “a Negro League Baseball Legend.”

I’m working on additional John Bissant posts that gets more detailed about his career and accomplishments, so hopefully that’ll be done soon. Fingers crossed!

It’s tough getting the stories told. Thanks to writers like yourself we still have a fighting chance. I encourage the family to keep pushing as I have and continue to do so. Families of those buried in that cemetery need to ban together to get it cleaned up.

LikeLike

Pingback: Clearing up a few John Bissant mysteries | The Negro Leagues Up Close

Pingback: Wrapping up the John Bissant story | The Negro Leagues Up Close

Pingback: Tragic lives in new Grave Marker Project efforts | The Negro Leagues Up Close

Pingback: The Negro Leagues Up Close