Editor’s note: The following article was graciously written by friend and fellow Negro Leagues fan Johnny Haynes. It’s a concise, on-point evaluation of the two segregation-era Black players on the National Baseball Hall of Fame’s recently-released ballot of candidates for the Hall’s Classic Baseball Era Committee.

Earlier this month, the Baseball Hall of Fame named eight players for consideration in the next class to be enshrined in Cooperstown. Much has been written about six of the men, but knowledge of the two Negro Leagues nominees seems to fall woefully short outside of Negro Leagues research circles. I will attempt to distill as much as I can into a more complete picture of the two pioneers up for selection into baseball immortality: John Donaldson and Vic Harris.

By Johnny Haynes, Article Contributer

John Donaldson’s groundbreaking career received some introduction to a new generation of fans in the popular MLB The Show video game series. His career spanned more than 30 years, though most of it occurred outside the confines of the organized Negro Leagues. By the time Rube Foster was organizing the first Negro National League in 1920, Donaldson was nearly 30 years old and had been pitching for more than a decade. As an aside, it was Donaldson who suggested naming the Kansas City entry the “Monarchs,” according to owner J.L. Wilkinson.

A brief statistical snapshot only tells a sliver of John Donaldson’s story; a casual fan looking up his statistics would find a .296 batting average in 817 at bats spread across five seasons. His recognized pitching statistics appear more mediocre: a 6-9 record and 4.14 ERA in just 22 games. According to Baseball-Reference, his comparable statistics place him closer to the likes of 1920s Indians backup outfielder Pat McNulty. The Seamheads version of his records paint a clearer picture but still only accounts for eight seasons of mostly independent ball.

However, one must consider the impact of John Donaldson on the game before and after his appearance in the “major leagues.” For decades after Cap Anson’s boycott of a game featuring Black players led to the infamous “gentleman’s agreement,” Donaldson remained an anomaly – a Black player on white teams. In addition, his barnstorming appearances on the All-Nations and Monarchs B side teams helped draw in fans and keep the lights on.

Admittedly, competition was mixed, but The Donaldson Network, which has chronicled the most complete snapshot of any Negro Leaguer’s career, lists him with 413 wins and 5,081 strikeouts across all levels of competition. For a stretch of time, no-hitters for Donaldson were nearly a yearly occurrence, including three in a row in 1914 and four in 1915. Double-digit strikeout totals were even more frequent on days he started.

Perhaps his achievements can be best measured in the accounts of his peers and the media of the day. So important was his appearance in a game in August 1925, a fan set up a camera and began filming as he worked on the mound. Consider that cameras in those days were expensive, cumbersome and rare. One can assume that the nameless fan that day was keenly aware of the greatness in front of him.

The highest honors were bestowed by his contemporaries. In 1943, Hall of Fame pitcher Grover Cleveland Alexander, who spent years on the barnstorming circuit alongside Black players himself, described Donaldson as among the greatest he had ever seen.

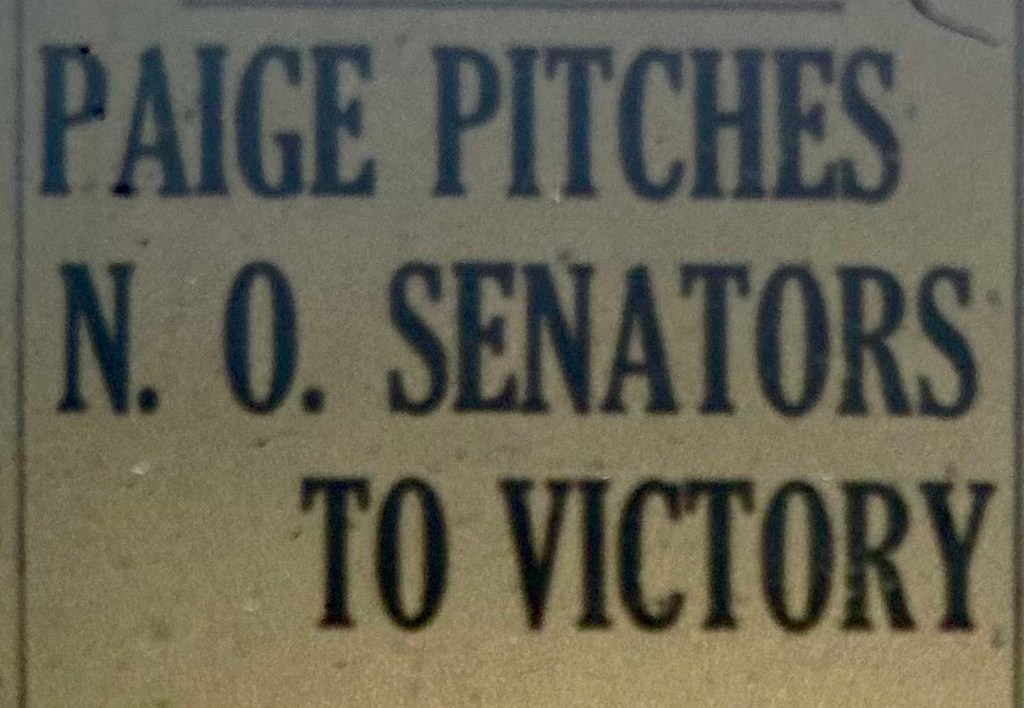

According to Buck O’Neil, he also pioneered the use of the slider, later teaching it to Satchel Paige.

In the waning last days of the Negro Leagues, the Pittsburgh Courier saw fit to name an “All-Time All-American” team in 1952. Of the seven pitchers named, only Donaldson is not in the Hall of Fame.

A bittersweet end to his administrative career post-integration is his tenure as the first Black scout for the Chicago White Sox. In an illustration of the quota system in major league baseball throughout the post-integration landscape, younger players such as Willie Mays and Ernie Banks were sometimes intentionally overlooked. It was the signing of Banks to the crosstown Cubs that led to his resignation and disgust with

*******

The second name on the list is even lesser known among baseball fans: Vic Harris. It’s worth noting that in MLB’s brief write up of Harris, they noted that Harris’ “exact numbers are hard to pin down,” which should elicit a chuckle from anyone in the baseball research community who has been studying the game for a long time.

Consider 19th century star Cap Anson. MLB notes that his hit total is 3,011, Baseball-Reference credits him with 3,435, and ESPN has a tally of 2,995. This discrepancy arises from a brief rule in which walks were hits and the inclusion of earlier portions of his time in the National Association. The Hall of Fame itself lists the Baseball-Reference numbers in his biography page.

As for Harris, a retrospective look at his career statistics is more complete than Donaldson’s, but I will admit that they too require additional context to understand clearly. Aside from brief stints with other teams early in his career, including the Cleveland Browns and Chicago American Giants, Vic Harris played for all three of Pittsburgh’s Black major league franchises: the Keystones, Crawfords and Grays. It is with the Homestead Grays that he made his greatest impact on the game.

Harris led the Grays to seven pennants and most notably a championship in the last ever Negro League World Series in 1948. At least two of those pennants occurred without the services of Josh Gibson, who had a three-year gap in his resume. Second on the list of most pennants is a six-way tie between Candy Jim Taylor, Dick Lundy, Frank Warfield, Dave Malarcher, Rube Foster and Jose Mendez, with three each. He was selected to the East-West All-Star Game seven times, and his 547 wins rank him first in Grays franchise history (Seamheads credits him with 631 factoring in independent, all-star and postseason play).

A register of everyone he managed lines up with a list of nearly every recognizable great player in Black baseball history: Leon Day, Satchel Paige, Buck Leonard and Josh Gibson are just a few of the names on a list that includes 13 members of Cooperstown. This and his record places Harris among the all-time greats to ever manage in the major leagues — regardless of race, era or league.

At the plate, Harris also maintained a steady presence in the Grays lineup. Mostly playing leftfield throughout his career, his currently listed statistics in league play include a .303 batting average, 738 hits and an OPS of .798 over 17 seasons. How’s all that for “hard to pin down” numbers?

As for my personal thoughts on the selection process in general: these two pre-integration Black men have deserved their due for a long time, as have many other players, managers and executives from that time in baseball history. The players on this ballot are all certainly deserving of consideration, but they benefit from playing in a time in which their careers occurred in an integrated game with much more exposure due to readily available accounts including television and radio.

Outside of the timeline and geography defined as the Negro Major Leagues, Harris made additional impacts as a coach on the 1949 Baltimore Elite Giants (who won an additional title following the merger between the NNL and NAL) before ending his career in 1950 after a season with the Birmingham Black Barons. In addition, Harris managed in the Cuban and Puerto Rican winter leagues.

Most baseball fans are aware of the likes of Dave Parker and Luis Tiant for this very reason. To include Donaldson and Harris among better known names — who come from a different time period — threatens to bury and diminish their accomplishments again.

Let’s keep in mind that the Negro Leagues were only recently recognized as a major league caliber operation by the same establishment that kept them out for 60 plus years, and the recognition occurred after most of the people who took part were dead. Coincidentally, another worthy post-integration Black nominee, Dick Allen, also faces consideration after he is dead. To be selected, a player must appear on 75% of the total ballots. All that said, it is my hope that the voters (who have yet to be revealed) do the right thing and select both in December.