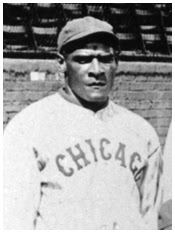

Last week I looked at the Hall of Fame case for Negro Leagues catcher Bruce Petway. This week the focus is on Frank Warfield, an Indianapolis native who gained fame — and notoriety — as a second baseman and manager from the mid-1910s to the early-1930s.

The argument for Warfield’s inclusion in the Hall is a bit more tenuous than that of Petway because, unlike the latter, Warfield had a reputation for volatility and ill-temperedness that occasionally bordered on violence. His penchant for ugly confrontations contributed to the hanging on him of the nickname “Weasel,” which seems less than flattering.

In addition, his achievements and status don’t seem to be as highly respected by his peers and historians. In other words, he just wasn’t as good as Petway. But we’ll try to lay things out and see where he falls.

One of the strongest arguments for Warfield is his record of overachievement — he was a little guy (about 5-foot-7) who exceeded expectations because of his grit and determination. An April 25, 1931, Baltimore Afro-American article under the headline, “They Laughed at Sox Manager When He First Sought Job,” explains his somewhat remarkable development as a player:

“Because he was so small of stature, most baseball managers laughed at Frank Warfield, manager of the Black Sox, when he tried to get a chance to do his stuff on the big teams …

“Warfield, who is one of the best second sackers in the game, started his baseball career on the old sand lots of Indianapolis …

“After playing on these lots for a considerable time, he tried to get a job playing with the big boys, but because of his smallness, no manager would listen to his plea.”

The article goes on to list some of the many attainments:

• A key cog in Hilldale’s three-year run (1923-25) of Eastern Colored League pennants (in the article Warfield asserts the Darby team was the best for which he played);

• Guiding the Baltimore Black Sox to a crown in 1929 and to several victories over assorted white all-star teams;

• Competed for strong Santa Clara squads in the Cuban Leagues.

• Much of his Negro Leagues exploits came while he was player/manager of various franchises, reflecting his splendid baseball acumen and ability to oversee other players and get them to perform at the top of their games.

Also remarkable was the fact that he broke in with the vaunted ABCs at the tender age of 15, which evinces his gutsiness and ambition.

Finally, while with Baltimore, he combined with Oliver Marcell, Dick Lundy and Jud Wilson to form the first “Million Dollar Infield,” predating the similarly-monikered Newark Eagles foursome nearly 20 years later.

However, Warfield’s numbers seriously weaken his case for the HOF. According to Seamheads, his career batting average in the Negro Leagues was a rather pedestrian .265, while his cumulative on-base percentage and slugging figures were .a bit more substantial .336 and .342, respectively.

He was also a speed demon, amassing 147 stolen bases, 118 doubles and 44 triples 843 Negro Leagues games, numbers that boost his case for the Hall.

Defensively, Warfield posted a fielding percentage of .949 and totaled 1,467 putouts, neither of which are too shabby.

In that way, it seems, Warfield was much like Petway — an excellent fielder, baserunner and manager who was hampered by light hitting stats. However, Warfield’s achievements as a team leader appear to have been highly esteemed at the time, especially his accomplishments with Hilldale. Here’s what the Feb. 9, 1924, Philadelphia Tribune stated:

“Hustling from the rank and file of the baseball world to the leadership of possibly two of the greatest aggregations of colored ball players ever gathered together, depicts in brief the meteoric rise of one, Frank Warfield, demure and unassuming, evasive of notoriety that accompanies par excellence achievements in any given line, yet possessing all of the essential qualities that go to make up a truly great ball player and being imbued with that indomitable spirit characteristic of all leaders, the diminutive second sacker has taken his place in the calcium glare. …

“Forsaking the shores of Lake Michigan last spring for those of the broad breezy Delaware, with the express intent of doing all the second basing that would be required by the Philadelphia Hilldale Club, Frank got by with the job with so much alacrity that the owners and the majority of the fans voted him a howling success, which is about as much as any ball player could desire, providing, of course, that the monthly stipend is hitting on all six.

“Coming down the stretch of a successful season, but with the crucial test to be reached, last October, the Hilldale craft, when apparently without a ripple on the surface, suddenly listed, careened and when it righted itself the berth of captaincy yawned with the vacancy of a cavern. Ed Bolden, who guides the destiny of the Hilldale outfit, summed up the possibilities for a field leader and hunted the mantle on quiet Frank. How the club finished out in front in the league race, how they turned back the Athletics and wound up the season in a blaze of glory is now history and ere Frankie hied himself from the Quaker City, he was named as the [?] captain of the Hilldale Club. …

“Truly with each club [Hilldale and Santa Clara], ‘Weasel,’ as some of his team mates have dubbed him, he has been staked to two of the best outfits that ever sported cleated hoofs and speculation is rife, regarding which team would emerge the victor, if a possible meeting between Hilldale and Santa Clara could be effected.

“But as it requires a big man for a big opening, despite Frank’s deficiency in statue [sic], the undersized Indiana youth has attracted the fans of Cuba and the States and now ranks with the select leaders in Negro baseball.”

Aside from incredibly convoluted and unnecessarily flowery languages — “cleated hoofs”? “calcium glare”? “yawned with the vacancy of a cavern”? — that passage, while superbly encompassing Frank Warfield’s proficiency as a manager, kinda glosses over (or, truthfully, outright contradicts) Warfield’s penchant for angry outbursts and involvement in physical conflagrations.

Because, well, there’s his temper, and what a temper it was.

His most notorious … let’s call it an incident … occurred in February 1930 while he was in Cuba as player/manager for Santa Clara. While Warfield and teammate (for both Santa Clara and the Black Sox) and fellow hothead Oliver Marcell were shooting dice — some reports say they were playing cards instead — a fierce fight erupted over the proceedings while several other players looked on. Let’s let the Feb. 8, 1930, Afro-American take it from there:

“Marcelle [sic] is said to have been losing heavily and asked Warfield for some money he claimed the Black Sox manager owed him from last summer. Upon the latter’s denial of the debt, Marcelle is said to have made a lunge at Warfield, and in the ensuing scuffle, Marcelle’s nose was badly bitten.

“The injured player is said to have obtained a warrant for Warfield’s arrest. It is understood that a hostile feeling had existed between the players for some time, started during last season. On several occasions Warfield is said to have removed Marcelle from the game because he was not in condition or not up to form.

“This engendered a resentment that smouldered [sic] until its outburst here. Both players are popular here and in the United States as well and the altercation came as a distinct surprise to the fans who turned out to see them in action. The case is scheduled to come up for an early hearing but the prevailing opinion is that because both of the players are Americans, the charges will be quashed.”

Keep in mind that these two guys were teammates at the time! In addition, Marcell’s nose wasn’t just “badly bitten” — according to historical accounts, his snoot was pretty much ripped off entirely. The injury is believed to have effectively ended his career, one that could have earned Marcell himself a spot in the Hall of Fame if it wasn’t for the physical trauma and his often uncontrollable temper. (Here’s an article I wrote a couple of years ago about “Ghost” Marcell.)

But Warfield was involved in a bunch of other highly publicized meleés as well. In July 1931, for example, a game matching the Black Sox and the Homestead Grays at Baltimore’s home grounds erupted into an ugly scuffle after Grays manager Cum Posey vehemently argued an umpire’s call in the eighth inning.

Posey — who was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 2006 — leapt from the Homesteaders’ dugout and rushed the field, promoting Sox player-manager Warfield to do the same. Warfield took offense to Posey’s presence on the diamond and demanded the the Grays pilot be removed.

According to the July 18, 1931, Afro-American, Posey allegedly responded with a cuss word or two, spurring Warfield to get up in Posey’s face. Cumberland, now completely incensed, punched the Weasel in the jaw, prompting several police officers to spring into action as multiple players attempted to restrain Posey.

According to the newspaper, if the cops hadn’t have intervened “there would have been some casualties.”

The paper added that it was, at the time, unclear whether Warfield had egged Posey on with his own volley of name-calling or physical jabs. Warfield denied anything “untoward” and alleged that Posey had called him names before. So nana nana boo boo, stick your head in doodoo.

The final example of Warfield’s rough temperament came in July 1925, while Warfield was on the Hilldale roster and the Darby clan squared off against Harrisburg. Allegedly, Harrisburg’s Dick Jackson got into a rumpus with Warfield, and Hilldale’s Clint Thomas reportedly tried to separate the combatants, only to be foiled by Hall of Famer and Harrisburg mainstay Oscar Charleston, who allegedly urged folks to let the two fight.

What apparently ensued was a fracas of the highest order, and it spurred spurred legendarily prickly Hilldale owner and Eastern Colored League president Ed Bolden to fire off a lengthy lament to the Pittsburgh Courier, which had earlier reported on the scrape:

“Under the caption of Oscar Charleston and William Nunn, sporting editor of The Pittsburgh Courier, I notice some charges and uncalled for lies in an attempt to spread propaganda against the Eastern Colored League and Hilldale.

“Some charges are so absurd that they are not worth answering I am TOLD [caps in original] that on Sunday, July 18, the Harrisburg players slammed one of the umpires and fought all over the Baltimore Park. For 15 years, we have had peace and harmony at Hilldale Park.

“Jackson, of Harrisburg, called Warfield a vile name. Thomas pushed them aside. Charleston rushed up pushed Thomas aside and said let them fight. Jackson hit at Warfield, Warfield ducked, knocked Jackson down and pounced on him. I do not encourage fighting on my team.

“Charleston’s poison tongue and foul tactics will never win the pennant. Baltimore, Bacharachs and Harrisburg have been materially strengthened through the UNDERHAND [caps original] methods of [Washington Potomacs owner] George W. Robinson. If Hilldale cannot win the pennant through wholesome sportsmanship and clean baseball, I do not want it.”

(The Courier returned fire by directing an open letter to Bolden, accusing him of fraud as ECL president via schedule more games for his on team and fudging league standings. The paper claimed it was simply asking questions — the source of Glenn Beck’s catchphrase? — with its previous report and that Bolden failed to adequately respond to them. The paper charged Bolden with, essentially, sensationalizing the Warfield-Jackson fight, as well as speaking out of both sides of his mouth when it came to his policy on fighting by his players.)

The Francis Xavier Warfield story came to a conclusion (at least corporeally) quite suddenly, on July 24, 1932, in Pittsburgh. According to his death certificate, the cause was pulmonary tuberculosis that was contracted in Baltimore, where he lived while suiting up for the Black Sox and which served as his adopted hometown. The document lists his occupation as “Manager” of a “Base-Ball Team.”

His exact age at death remains a little unclear, with different records listing different dates of birth. The death certificate states his birthdate as “unknown” and pegs his age as “about 33.” His World War I draft card gives his DOB as April 26, 1898, while certain Social Security records say Sept. 14, 1894. Birth records list the DOB as Aug. 15, 1898, but Find A Grave asserts April 26, 1897. Finally, the 1900 Census says September 1889!

(What’s also unclear is the Weasel’s place of birth; while it’s clear that he did, for the most part, grow up in Indy, possible birth locations include Indy; Warrick County, Indiana; and Christian County, Kentucky, where his ancestral roots appear to have been.)

The Afro-American reported the circumstances, citing “an internal hemorrhage” as the cause. The paper added:

“Death was almost instantaneous. Warfield had been in good spirits and in apparently good health, and only Saturday night talked over long distance telephone with friends here. Early in the season, he contracted a cold, and while it did not respond to treatment as rapidly as expected, it was not thought to be of any serious consequence.

“For several weeks, Manager Warfield graced the bench during games, although he occasionally took part in practice. His place at second base was taken by [Sammy] Hughes … and the youngster handled the position so well that Warfield did not feel it advisable to take him out of the game, so he directed the team from the bench.

“Just 34 years old, Warfield was at the peak of his managerial career when death came. …”

James Riley, however, in “The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues,” relates a slightly different tale of Warfield’s demise:

“He was still officially serving in the capacity of playing manager when he died of a heart attack under vague circumstances. A known ladies’ man who liked to flash big money rolls, he was in the company of a woman when he was rushed to the hospital, bleeding. His death was almost instantaneous after suffering an internal hemorrhage.”

But back to the Afro article, which went on to eulogize Warfield with his achievements and personality traits, the description — such as “[a]lways quiet and modest” — of which by the paper seem to contradict the numerous accounts of his short fuse and proclivity for scrums.

However, the newspaper also assessed Warfield’s hardball faculties pretty accurately:

“In addition to having baseball brains, Warfield was a fast base runner and a good hitter, throwing and batting right handed. It has been often said of him that he could get more passes to first base than any other man in baseball. He had a knack of worrying pitchers as he ‘waited out’ their pitches and some of the best hurlers in the game used to dread to pitch to him, not because he was such a heavy hitter, but because he worried them.

“Years ago, some team mates named him ‘The Weasel,’and true to that namesake, Warfield proved to be a clever strategist. He was a master of the sacrifice bunt and he beat out many an infield hit. He studied the game and while pitchers were often credited with winning games, it was the strategy of Warfield that was really responsible.”

And this is what the Pittsburgh Courier wrote:

“Death, coming after a brief illness, robbed Negro baseball of one of its finest and most able performers and one of its most respected players by fans and officials alike.

“… His work as an infielder was brilliant but steady, and many clubs made bids for his services. His fine record as a player and a gentleman and his contribution to baseball ranks him with such immortals as Rube Foster and C.I. Taylor. …

“Possessed of a cool, even temperament, and with plenty of business as well as baseball brains, Warfield made an ideal manager. In addition to handling the team on the field, he was efficient as a business executive of the club and took charge of most of the financial affairs.

“The remains were shipped to Baltimore for burial, his present home where hundreds of messages of condolences from both high and low in the baseball world attested to the esteem in which he was held.”

And from the Philly Tribune:

“Warfield was long considered one of the most astute performers in the game. …

“It was under the banner of the Darby Daisies … that Warfield reached the heights as a player. He was termed the ‘miracle man’ and was generlaly [sic] rated as the peer of all Negro second basemen.”

So, the question could be … How do you elect to the Hall of Fame a man who bit off a teammate’s nose, who drew a Hall of Fame manager into a fight, and who helped trigger an ugly brawl on at least one additional occasion? (And that’s not to mention his relatively lightweight numbers at the plate.)

Because of the arguments that can be made in favor of him, that’s why — his incredible managerial aptitude (that were so good that he garnered comparisons to Rube Foster), his fleet-footedness, his shining defense, his record of success despite originally being dismissed as a little squirt.

Again — as with many HOF candidates, regardless of era or ethnicity — it’s quite cloudy and hazy. Greatness is never completely three-dimensional: Ty Cobb and Cap Anson were angry, racist jerks; Ted Williams and Josh Gibson were at best so-so on defense; Ozzie Smith and Bill Mazeroski were pedestrian at the plate; Nolan Ryan and Phil Niekro piled up almost as many L’s as W’s. And that’s not to mention the many greats who might always be on the outside looking in — Pete, Joe, Barry, Mark …

For me, Frank Warfield is a toss-up when it comes to Hall of Fame induction, with his stormy personality being the best argument against him, and his underrated managerial acumen the top “pro” factor.

How about you?